A singer in full flow, channelling words and melody from a source within and beyond them. A songwriter in full flow, also channelling, words growing on the page or in the throat, melodies and harmonies branching out and bedding in. Singers, songwriters and songs coming into form, deforming and reforming in an unfolding present that carries past into future.

Richard Dawson talks about the song ‘Wooden Bag’ unfurling into its final shape. Narrative theorists tell us that the shape of a story only becomes clear on its completion. But we also make sense of things as we encounter them, not waiting for the end. This paradox lies at the heart of the tension between processes and things.

Add memory to the mix, and our need for objects expands. Unearthing things in a memory box, a wooden bag or a glass trunk can return forgotten memories and place them in time, space and order. To tell a story requires anchors, what we’ve learned from cultural theory to call ‘quilting points’.

Museums and archives provide tangible examples of how the objects of the past can work as connections to the present, offering the possibility for stories to be told in many ways.

The songs written by Richard Dawson for The Glass Trunk (2013) offer one way of doing justice to the past through its objects. Dawson was invited by the Tyne and Wear Archives and Museums to contribute to a project entitled ‘Half Memory’. His brief was, in his own words, ‘to go into the Discovery Museum’s archives and search for anything’, then to make half an hour of music.

As he explored this memory box of the region’s past, his attention was caught by a fable in an old scrapbook concerning the brutal murder, in 1826, of Joseph ‘The Quilter’ Hedley at his home near the Northumberland town of Hexham. Hedley’s life and death had already been narrated in twenty-six verses published as a broadside under the title ‘Joe the Quilter’. The verses are reproduced in Rosemary E. Allan’s Quilts & Coverlets, a book about quilting in the North East of England and the collections held by the Beamish Museum in County Durham.

From these verses and other texts in the scrapbook, and with additional details gleaned from Rosemary Allan’s book, Dawson fashioned his own long ballad ‘Joe the Quilt-Maker’:

Following the general shape of the story I rewrote the words utilising the established verse-structure and let the song inflate until it was ready to burst … twenty-six quite verses sitting on a page … The song ballooned further to include some … of the important detail provided by the book: A pair of bloody clogs, remnants of scalp on a garden hoe, defensive wounds on the victim’s hands.

—Richard Dawson, liner notes to The Glass Trunk

‘Joe the Quilt-Maker’ became one of seven songs with words on The Glass Trunk. The album also contains twelve instrumentals performed by Richard Dawson on guitar and Rhodri Davies on pedal harp.

Dawson’s account of how he ‘let the song inflate’ resonates with his description of writing ‘Wooden Bag’, giving an interesting agency to the song itself. ‘Joe the Quilt-Maker’ doesn’t dwell on the quilt as object, but rather on the tragic history of its human subject. However, there’s a fragility to the song that invites consideration of it as a quilt, as something sewn together and prone to fraying.

In the Glass Trunk version, Dawson’s voice frequently disappears into whisper and wheezing, suggesting an exhaustion of breath. The impression is of a song that could fall apart but remains held together at the edges. Following the quilting analogy, I hear the fraying of the voice as the unravelling of Joe’s life.

It turns out Dawson had, indeed, been thinking of quilting when writing the song, but he recalls that the recorded performance differed from his original plan:

I’d certainly designed it with the idea that it would be like a musical quilt, but the performance choice was just an in-the-moment thing. It just felt like the right way to do it. I like it, though. … You could argue that I had a sense of it being the correct way to deliver it because of these things. But, no, the plan was to bellow it really, but it just wasn’t working on the day … [To] go much smaller and closer up was more appropriate.

—Richard Dawson, interview with Richard Elliott, 3 August 2019

Dealing with real lives and events is central to Dawson’s approach to songwriting and is both a reason for, and outcome of, his extensive research processes. In speaking about the songs he wrote for Peasant and 2020, as well as non-album projects such as This Liberty (for which he wrote songs to accompany Matt Stokes’s film about Hexham Old Gaol), he emphasises the responsibility he feels towards his subject matter, relating this to the songwriting process for ‘Joe the Quilt-Maker’:

This is somebody whose life is documented, so how do you justice to their existence? They were as real as you and me sitting here now, so how do you pay tribute to that? And I think one of the ways is learning about quilting, about some of the methods, learn about the topography of the area where he lived, the plant species. You know, just to put yourself there.

—RD, interview with RE, 2019

There’s that emphasis on research once more. Like checking that Anadin Extra existed in the mid-1980s for ‘Wooden Bag’, reading up on botanists for Henki, mastering a bewildering array of former-worldly vocabulary for ‘The Hermit’. I asked about this again when Richard and I spoke at the Tusk North festival in 2022. I pointed out that Henki songs like ‘Cooksonia’ and ‘Methuselah’ contained an unusual level of detailed research. ‘Isn’t that strange, though’, Richard responded, ‘because it wouldn't be a surprise to find it in a book or a film. You would expect it, otherwise it’d be really weird’.

What is the potential of song to do this kind of work?

‘songs hanging like bowls in the air’

How do you do justice to a life and to a community?

Perhaps you find one of Joseph Hedley’s quilts, or use ‘Old Joe’s Chain’ as a design in your text.

Or you remember that folk songs are built on fragments of other folk songs and that piecing them together is a craft passed on, practised and perfected, just like quilting.

You sing ‘The Brisk Lad’ by taking what Mike Waterson has done with it and shaping it how your body shapes it. Others did it before you, more will follow. It appears on Stick in the Wheel’s A Thousand Pokes in October 2024, and you know it’s safe for now.

You spotlight a community of song by finding opportunities to write about it in your liner notes, interviews and concerts.

I bought a copy of the solo album he [Mike Waterson] recorded in the seventies and liked it a lot. Feeding on it, and things by Huun Huur Tu, Tenores Di Bitti, Phil Minton, Bach and bunch of other cats, I found myself thinking more and more about the possibility of making an album of unaccompanied singing. Another thing which pointed me in the direction was seeing Cath Tyler perform solo around about the same time at Morden Tower in Newcastle … I was struck by the starkness of her performance and the fragility of the songs hanging like bowls in the air, both incredibly direct and impossible to grab. Cath and Phil Tyler … are incredible musicians (people) who’ve introduced me to a good deal of spectacular shit—not least Sacred Harp singing, which is inspiring both for the gusto of its delivery and the spirit of community which it promotes.

—RD, liner notes to The Glass Trunk

You take those ballad verses from ‘Joe the Quilter’ and you do what other balladeers have done. You make them your own. You add verses that didn’t exist for a story that did, and you make a dark and beautiful poetry.

I found a pair of clogs in the lane Some drops of blood where they had lain And following the breadcrumbs I came upon the dreadful Remains of Joe the quilt-maker

Rhymes rise from the language as it unfurls: lane lain remains, clogs drops, blood bread, bread dread. And always the refrain of Joe the quilt-maker.

Song does quilting better then prose because it has more patterns.

When I do fragments, there’s always the danger they won’t form a pattern, that they’ll fall apart. I don’t have the technologies of song to hold things together: the stitching, the symmetry, the verse and refrain. I have only the wonder, and the desire to try and capture it for a moment.

Quilts, like the Chilean arpilleras that Marjorie Agosín writes about, are ‘scraps of life’, storytelling devices that rely on domestic objects and which themselves become domestic objects.

Quilts are memory blankets. Each scrap represents something that was touched, used, worn, loved, or worked in. A fragment of cloth may be all that remains of a life it was once part of.

Beyond the needs of mere survival, there was a spiritual dimension to these quilts. They recycled what were often the only surviving possessions of deceased spouses, parents, siblings, or children, thus holding the power, or at least the memory, of departed loved ones.

—Text from the online exhibition ‘Gee’s Bend: Work Clothes Quilts’, Souls Grown Deep Foundation

Arie Pettway’s quilts, which use the ‘bricklayer’ pattern, bring aesthetics and function together on several levels. They are visually engaging, dynamically coloured and patterned, useful as coverings, and a reminder of how pattern and function are crucial for the craft of building. The hardness of the represented bricks (or ‘courthouse steps’, as the pattern is also known: another hard image) is undercut by the softness of the quilt. Something similar cam be said for the cotton work clothes they are made from.

A collection entitled Quilt Stories, edited by Cecilia Macheski and published by the University Press of Kentucky in 1994, gathers stories, poems and reflections on the role of quilts and quiltmaking in the United States. One of the excerpted works is Whitney Otto’s How to Make an American Quilt, and it reflects on the dullness of the work.

You personally find the piecing together of the work tedious—arduous and dull. Likewise for cutting the pieces, securing the batting between the back and top work. But you find the designing and creation of the quilt theme exhilarating. As if you are talking beauty with your hands. Make yourself heard in a wild profusion of colors, shapes, themes, and dreams with your fingertips. The tedium of quilt construction some days can make you cry; you long to express yourself. To shout out loud in silk and bits of old scarves.

And:

You should share the work but not the idea behind it. You understand this. But in a small, close circle it is difficult to do this. You trust the Hawaiian notion that to share your personal pattern is to share your soul. To compromise your power.

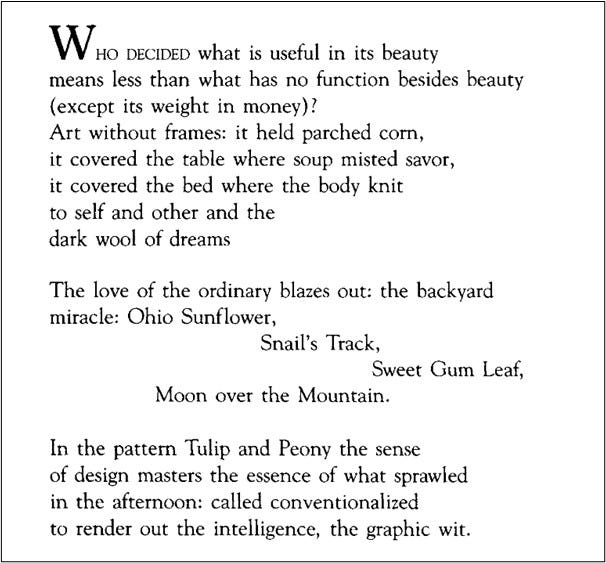

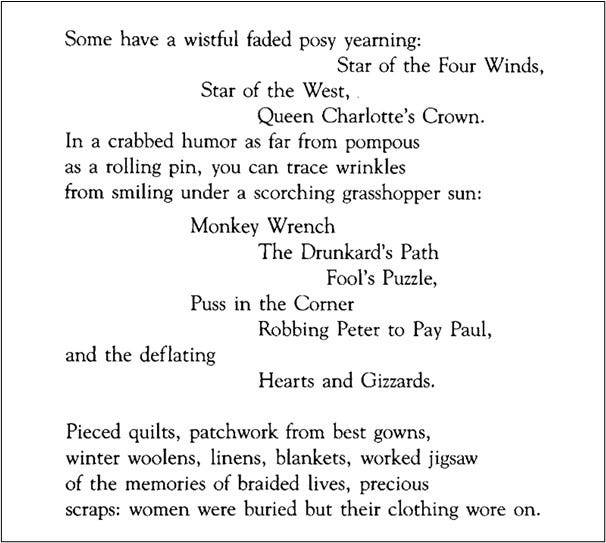

From the same collection: Marge Piercy’s ‘Looking at Quilts’, a poem about the everyday beauty and functionality of quilts that sits on the page like a quilted pattern.

This emphasis on function—‘as far from pompous / as a rolling pin’—reminds us to look beyond the aesthetic, pleasant as that is, and to ask: what do quilts and poems and songs and other arts and crafts do?

When it comes to song, that’s a question I’ve asked here often. I don’t have definitive answers, of course, and that helps to keep the question potent. To raise it again with ‘Hoe the Quilt-Maker’ in my ears, and in the context of arts, crafts and memory work, is to underline Richard Dawson’s comments about the ethics of songwriting, of wanting to be true to his subject matter, to do it justice. It’s a reminder, too, of a desire for song, or singing, to be something that people do.

When we met in 2019, I mentioned to Richard my idea of human and nonhuman songholders, vessels that carry, store and make available songs (and therefore stories) which might otherwise be lost or forgotten. Richard was sympathetic to the idea, likening my ‘songholder’ to ‘torchbearer’. I didn’t know, at that time, about kennings or the Viking skald Egill Skallagrímsson’s use of ‘song weigher’ in the poem ‘Sonatorrek’.

‘How do you get over something which has pulled you apart?’

To treat songcraft as quilt-making would be one way to do justice to a quilt-maker. If the song is a patchwork, its rhymes and refrains are quilting points, moments that hold together what might otherwise unfurl. In Richard Dawson’s songs, these quilting points are vital given the tendency for the song structures to veer about in unpredictable ways.

The angular, spiky pieces recorded by Dawson and Davies that are placed between the songs on The Glass Trunk are like curious musical exhibits.

As we discussed ‘Joe the Quilt-Maker’ back in 2019, Richard made a connection to his previous album.

I know it ends badly, but there’s such a lot of the song [that] is very happy. There’s his time with his wife at the start and then getting over that loss and getting back to work and how he grieved but then overcame his grief through work and through craft. I had not thought that out loud but that actually ties in with The Magic Bridge album; that whole album is around that topic: how do you get over something which has pulled you apart? How do you regain your balance?

RD, interview with RE, 2019

Richard was right about ‘Joe the Quilt-Maker’ being a song to bellow out. I may have been thinking of the almost-whispered, frayed performance on The Glass Trunk when I spoke with him in 2019. But the Barbican performance from the following year (from 40:06 in this video), in which the full-throated singer captivates a London crowd for twelve minutes, is the one I go back to now.

It provides all the evidence I need to declare Richard Dawson one of the finest balladeers we have in our community. For someone to build a song like this from patches available in books and archives, and from a formidable knowledge and command of the British ballad tradition, to be quiltmaker, bricklayer, songholder, torchbearer, captivator: that is how to do justice to those whose stories it befalls you to tell.

”Women were buried but their clothing wore on” — unforgettable.

I really appreciate your write-up, which makes it easy to understand the artistry -- you make a compelling argument for his skill as a songwriter.

I admit, that his singing style is a barrier for me. I liked "Wooden Bag" but it helped to read the lyrics beforehand, and I would not have understood "Joe The Quilt-Maker" without your notes.