I’m devoting my next few posts to the work of one of my favourite singer-songwriters, Richard Dawson.

There are a few reasons for this. One is that, as I mentioned in my recent anniversary post, I need to steer this newsletter back towards supporting the book project I’m working on, the one that gives Songs and Objects its title and main theme. Richard Dawson’s songs were among the first I thought of when I started preparing the ideas for the book, and I see his work as foundational for much of what I’m doing with it.

Another reason is that I wrote an article about Dawson’s songwriting five years ago for an academic journal that has yet to launch. Five years is a long time to wait for a publication, even by the glacial standards of academia, and I have made the decision to share that work in a format more suited to Substack. That means dividing the article into two or three parts (I think three will work best) and removing or reworking some of the theoretical framework needed for the journal but less relevant here.

A third reason is that Dawson has a new album due in February 2025, and it’s likely I’ll want to write about that project when it arrives. I’d rather have what I’ve already written about his previous work available as a reference point than start from scratch again. This was an issue I found late last year, when I wrote about Dawson’s 2022 album The Ruby Cord and the 2023 concerts that followed it; again, it would have been more coherent to build those reflections on the 2019 article, had it appeared as originally scheduled.

This first part of my exploration of Dawson’s work from a songs-and-objects angle focuses on ‘Wooden Bag’. First I provide a bit of background information, then I get into the song, with my reading complemented by some things Dawson discussed with me when we met for a first interview in 2019.

‘The Minutiae of Things’

In a 2008 review of Evocative Objects, a collection of essays edited by Sherry Turkle that had been published the previous year, the philosopher Graham Harman wrote, ‘Surely even the dullest of objects are laced with songs and legends that await their bards’. That’s an observation I very much agree with and it resonates with what I’m trying to get at in Songs and Objects. And for me, one of the preeminent contemporary bards responsible for uncovering the hidden lives and meanings of everyday objects is the Newcastle-based singer-songwriter Richard Dawson. Over the past ten to fifteen years, Dawson has established an international reputation as a crafter of uniquely themed and composed songs and as a dynamic live presence.

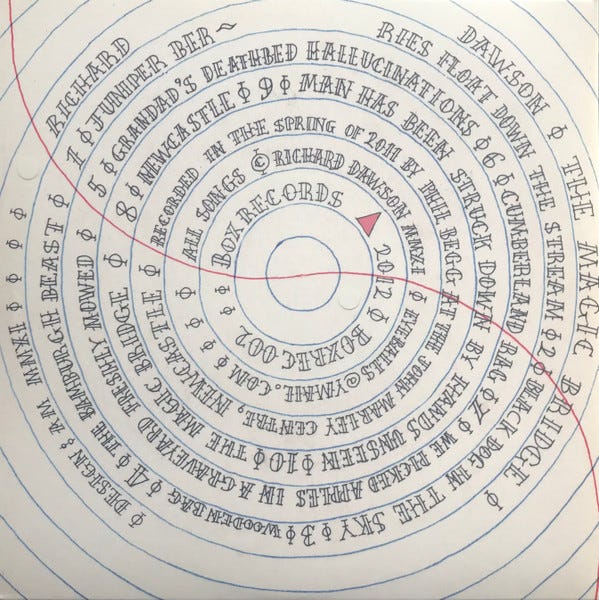

Things really took off for Dawson nationally in 2014 with his fourth solo album Nothing Important, released on Domino’s ‘Weird World’. The album received widespread critical acclaim as well as support from British radio DJs Marc Riley and Stuart Maconie, and Dawson began to tour more widely as his audience expanded quickly from its core base in the North East of England. Domino subsequently reissued two of Dawson’s earlier, independently-released albums The Magic Bridge (2011) and The Glass Trunk (2013), as well as new albums Peasant (2017) and 2020 (2019); the new albums were again well-received, as were appearances at a wide variety of concerts and festivals.

At the time I wrote most of the observations here, 2020 was Dawson’s most recent album. Since then, he’s released an album with his fellow band members in Hen Ogledd (Free Humans, 2020), a collaboration with the Finnish rock band Circle (Henki, 2021), and The Ruby Cord, a double album released under his own name in 2022. Oh, and there’s the small matter of the eighty-odd albums he’s made with Sally Pilkington since 2020 under the name Bulbils. Dawson is nothing if not prolific.

As national and international reviews, interviews and features appeared following the critical success of Nothing Important, it became possible to trace and triangulate certain recurring themes that critics and fans were finding in Dawson’s work. Among these were the unusual subject matter of his songs and the distinctive musical styles and structures employed. In terms of lyrical content, Dawson’s work often highlights what Johny Lamb, writing for the Quietus, termed ‘the minutiae of things’, an accumulation of seemingly unremarkable details made remarkable by his songs. Record Collector’s Mike Goldsmith, meanwhile, noted Dawson’s ‘intricate yet naturalistic lyrics that skewer the minutiae and detritus of life’.

While it may be a general feature of popular music that songs inevitably deal with—and therefore amplify—small details of everyday life, many fans and critics note the simultaneous mundanity and oddness of the objects which appear in Dawson’s lyrics. These objects are mundane inasmuch as they are artefacts of the world with which many of his listeners are familiar, yet they are odd because of their rarity as song lyrics; there simply aren’t that many songs which feature Phillips-head screwdrivers, bars of Highland Toffee, Woolworth’s price stickers, trolleys and snooker cues. As the musician Cian Nugent observed in a feature for BOMB,

[Dawson’s] music is familiar and unsettling, like some half-remembered childhood moment that comes up in the midst of a god-awful hangover, crippling in its sweetness. … He regularly brings us back to the sober present with a bang through his savage commitment to the idea that his songs be about real life, not some fantasy of what a song should be about. His songs mention WHSmith, Asda, Anadin Extra, Newcastle United: places and things that hover around the margins of the average UK consciousness, and that most of us are not used to hearing sung about at all.

Reviewing Dawson’s album 2020 for Pitchfork, Sam Sodomsky picked up on the unusual aspect of the lyrics, reporting that ‘Dawson took inspiration from conversations he had with fans at shows, and his intimate tone makes you consider words and phrases you’ve never [heard] in a folk-rock song before: dehumidifier, voluntary redundancy, Nando’s’. Sodomsky also identifies a ‘combination of banality and mythology’ in the songs, and claims that ‘Dawson succeeds by finding surreality and horror in his everyday musings’. Jennifer Lucy Allan compares the medieval-themed, otherworldly Peasant album with the recognisably contemporary British settings of 2020 as follows: ‘Where the characters who inhabited … Peasant were coated in mud and twigs, those on … 2020 are mired in brands and stuff: Nandos, Premier Inn, Bags For Life, vapes, Zoopla, Aldi, the Red Cross – it is a litany’.

Dawson himself noted in 2019 how his recent songs reflected ‘what our experience is when we step out the front door… If you're going to paint a picture of the world actually as people see it, then rather than describing the shape of the landscape, our landscape is products and big bright words; plastic things. Our whole lives are geared around the acquisition of these things’.

The dynamic tension between mundanity and strangeness in Dawson’s songs is one of the many things that has fascinated me since I first became familiar with them in the late noughties. More recently, when I decided to start working seriously on my Songs and Objects project, Dawson was one of the songwriters whose work guided my thinking and who I knew I wanted to include in the project. In August 2019, Richard Dawson was kind enough to agree to an interview and we had a long and wide-ranging conversation in my office at Newcastle University. We discussed a selection of his songs and Richard responded to my object-oriented approach, providing some fascinating insights into his thinking about songs, objects, people and the role of the songwriter.

‘Wooden Bag’

One of the first things that struck me about Richard Dawson’s music was its intense and intimate reflection on objects. Witnessing several live performances around the release of The Magic Bridge in 2011, I found myself particularly drawn to the song ‘Wooden Bag’. For me, this song resonates with other works of poetry and prose that dwell on evocative objects, witnessing and technologies of memory: Jorge Luis Borges’s short story ‘The Witness’; Fernando Pessoa’s Book of Disquiet; Joe Brainard’s I Remember; George Perec’s Je me souviens and his ‘Notes Concerning the Objects that are on My Work-Table’.

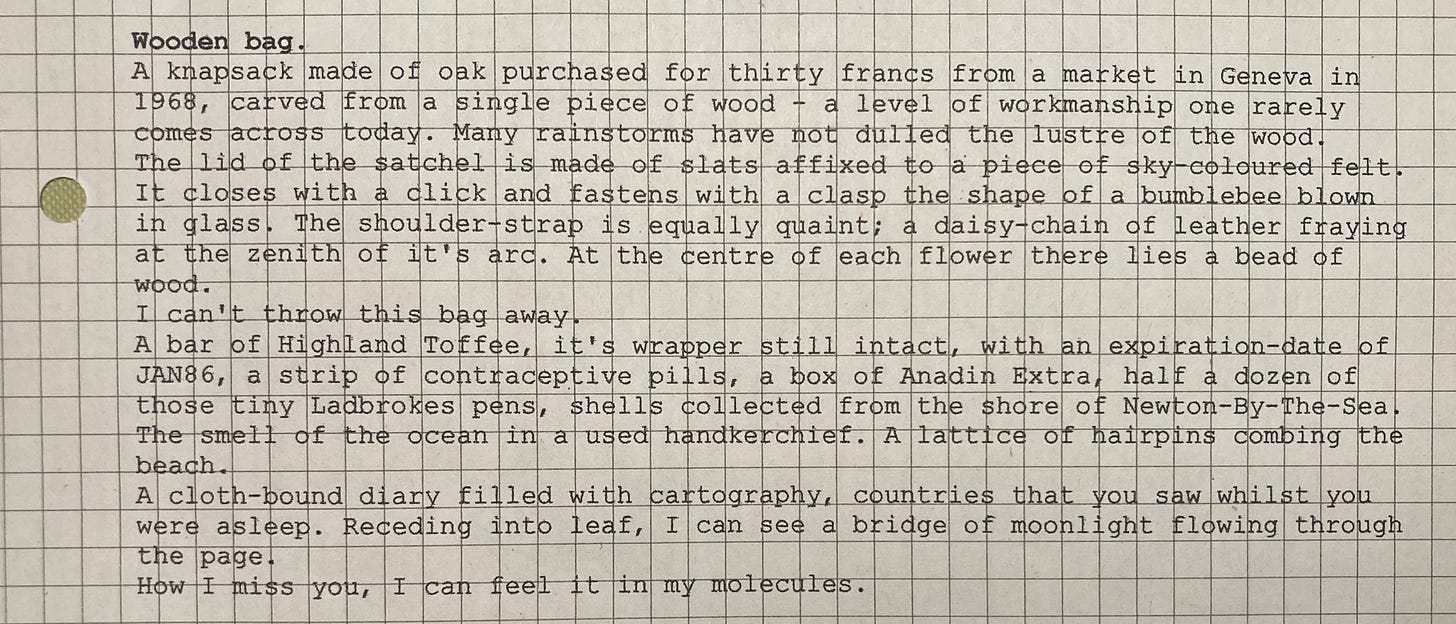

Like these texts, ‘Wooden Bag’ represents several objects that are both unusually detailed and evocative of witnessed lives. The song’s opening line reads like a description from a catalogue: ‘A knapsack made of oak, purchased for thirty francs from a market in Geneva in 1968’. The first verse continues the almost neutral descriptive tone: ‘almost’, because some evaluation does enter when observing ‘a level of workmanship one rarely comes across today’, one of the many unusual lyrics that the song yields. The bag’s outer and inner casing are described, along with the strap and the clasp.

The photo below shows how the lyrics are formatted on the insert that came with the vinyl version of The Magic Bridge in 2012. As they may prove difficult to read due to the squared paper, I’ve also put the first verse as a block quotation, formatting it as verse (I’ve copied this from the lyrics at Genius, as I feel the rendering does justice to the line breaks as sung; it’s essential to hear the song, though).

A knapsack made of oak Purchased for thirty francs From a market in Geneva In 1968 Carved from a single piece of wood A level of workmanship one rarely comes across today Many rainstorms have not dulled the lustre of the wood The lid of the satchel is made up of slats Affixed to a piece of sky-coloured felt It closes with a click And fastens with a clasp The shape of a bumblebee Blown in glass The shoulder strap is equally quaint A daisy chain of leather Fraying at the zenith of its arc

A second verse lists the contents of the bag: a bar of Highland Toffee, some contraceptive pills, a box of painkillers (specifically, Anadin Extra), sea shells, a handkerchief, a cloth-bound diary and ‘half a dozen of those tiny Ladbrokes pens’. After each list-like verse, Dawson adds a refrain that moves from neutral listing to the emotive cry of ‘I can’t throw this bag away’, its second iteration prefaced by the declarative ‘How I miss you, I can feel it in my molecules’.

Here’s a live version of the song, which sticks closely to the version recorded for The Magic Bridge. I’ve selected this one because it gives a good sense of the intensity of a Richard Dawson concert.

‘Wooden Bag’ is striking for its presentation of detailed descriptions. Most of these objects are ones we do not typically find in song lyrics, even while—apart from the bag itself—they are everyday objects, things we take for granted. Indeed, it is the very unremarkability of the objects that makes them so remarkable. The everydayness of the objects can function in at least two ways: firstly as a point of recognition for listeners who share the cultural world of these objects; secondly as a transferable or translatable object that—for an unfamiliar listener—still points towards a shared recognition for evocative objects.

When interviewing Dawson, I mentioned the Ladbrokes pen as an example of the former type of object. This object would be familiar to many of his British listeners, even some who had not frequented a branch of the betting chain. By singling out a tiny pen or a strip of pills as a way of communicating to others, both parties can recognise an unusual specificity and a shared experience. Dawson agreed:

[A]nybody listening who has an experience of that pen, it would be specific to that listener … it taps into whatever experience they were having when they experienced that pen. The same with Anadin Extra, which is something [where] not only do you have the object itself, with the design on it, but you have the sound of the object—quite a powerful thing, maybe with the half-used foil lifted up—but also everybody’s going to have a strong memory of a painkiller. Even if it’s not Anadin, it’s still going to have an effect because these big moments: why would you need a painkiller? It’s going to be some injury has occurred or some ongoing injury that you have, so again it’s such a commonplace thing and not specific, but the memories it will bring up for someone are really specific. So it’s both at once. (Personal interview, 3 August 2019)

The dialectic of the particular and the universal also arises in ‘Wooden Bag’ through its mention of the Northumberland parish of Newton-by-the Sea. While recognising my suggestion that this is a welcome local reference point for listeners who know the North East of England, Dawson was keen to note that ‘Everyone’s got a Newton-by-the-Sea somewhere near them as well’. Again, the dual nature of the lyric object (in this case a place) means that many listeners unaware of Newton-by-the-Sea will still get the reference to place and also be familiar with hearing places being used in poetic ways in songs.

This could be thought of as a way of making the everyday weird. Dawson’s work has been associated with the weird, strange and freakish, from the release of his records by Domino’s Weird World imprint to his appearance on shows such as Stuart Maconie’s Freak Zone and John Doran’s New Weird Britain. Dawson, however, retains some suspicion towards the weird tag:

I don’t know if I’d use the word “weird”, but you know there’s two things going on. There’s this idea of, you know, using objects which are familiar, everyday, commonplace, and so they maybe have this effect of connection with people, and they also serve as kind of dates and they set the song in time maybe … [‘Wooden Bag’] mentions that the Highland Toffee bar in the song has got an expiry date [“an expiration date of JAN86”], so the Anadin Extra, I had to make sure that existed then, and it did. Otherwise it would have had to have been a different painkiller. But they often have this more hidden, practical thing of painting, there’s more information in them [which] can convey a lot about the time and the setting … I don’t think I would necessarily say “weird”, but there is something about when you put this focus on something like this and place it maybe centre stage in a sentence, or when you do that with a melody, that’s how you place that thing. Or maybe it’s the object that pulls the melody a certain place. But it becomes almost like a totem. (Personal interview, 3 August 2019)

It has become clear from Dawson’s interviews that he is keen to do justice to the things, people and events he writes and sings about. This may manifest itself in a rigorous approach to historical detail (be that the branded commodities in ‘Wooden Bag’ or the songs based on items in the Tyne and Wear Archives that form the basis of The Glass Trunk) or in allowing a song to take the lyrical and musical shapes that emerge during the writing, recording and performance processes. This can lead to a tension between the stubborn persistence of objects in our lives and a sense of the ephemeral when it comes to dealing with human connections. In his song ‘Nothing Important’, to which I’ll return in a future post, Dawson highlights this tension by presenting lists of objects that have taken the place of the person to whose life they bear witness. In contrasting the present objects with absent people in that song and ‘Wooden Bag’, Dawson suggests that objects are necessary but sometimes unfortunate substitutes.

So maybe we fall back on objects, but the objects aren’t the important part of it … I think we connect with objects and through objects as well, and, particularly in this country and some others too, we sort of celebrate the object above the experience, and maybe also the getting of the thing above the thing … I think what most people want is a connection between people, and for that to somehow remain and exist in a real way we do it through objects and I think our focus goes in the objects. (Personal interview, 3 August 2019)

Dawson’s caution about investing too much attention in objects at the neglect of communal bonds could be related to thinking of songs as objects too. Here, what he says resonates with something that the songwriter Will Oldham has said. In one of the comments included in his lyric collection Songs of Love and Horror, Oldham writes, ‘The primary intention of [my] works is to provide platforms (or excuses) to commune with others: with people I love, musicians I revere, and audiences who feel similarly desperate for connection’. While such accounts present objects as scripts for the creation of more important experiences (performances, communication), I’d argue that this only enhances the importance of the object; Oldham’s comment introduces a printed collection of song lyrics, after all.

While discussing the dialectic of music as thing and process, Dawson referred to artistic techniques whereby treatment of objects in systematically descriptive ways can lead to interesting transformations or effects. Examples of this from literature include works like Alain Robbe-Grillet’s Jealousy or George Perec’s Life A User’s Manual. Of the former, Dawson notes its reliance on flat descriptions of objects and scenes as an influence for ‘Wooden Bag’:

the idea was for it to just be a description … I had this idea that it was a person describing a person who’d lost someone—a partner, or a parent, or even a kid—but that it would just be reserved and wouldn’t lose its composure at the end. It would just be a coolly described list. [Jealousy] just describes a house and the weather and the angles of the light as it changes and a certain stain on the wall and the grain in the wood on the decking and it goes back to the light. And this book unfurls and it goes on about the lamp, how one tassel is slightly caught and lifted up and it keeps going on. But what you have is this seemingly complete picture of an environment. So that was the plan with that song but then it leads its own way and I’m like “I’ve got three lines left” and then the emotional response breaks through. (Personal interview, 3 August 2019)

Discussing the effect that the writing process had on the ultimate direction of the song, Dawson contrasts the writer’s plan and then what ‘comes through’ in songmaking. In the same way a songwriter has to do justice to the people and things they write about, Dawson suggests, there’s a need to do justice to what the song wants: ‘the longer I’ve done it, I’m more and more convinced that it’s a living thing, that it’s a sentient living thing making itself known. And when you have the experience of this—it not being there one moment and then it’s present—then you just have to follow that, and do it right’.

While not denying the amount of refinement necessary to craft songs from initial inspirations, Dawson has come to feel that there is ‘some kind of intelligence that has to take a recognisable shape’. This intelligence comes partly from the accumulated experience of being a songwriter, but also from the inherited affordances of musical styles, the language ones writes in, and so on.

From an object-oriented perspective, I’d want to supplement Dawson’s account of the agency of song with a recognition of the vital existence of the objects depicted in a song such as ‘Wooden Bag’. To place the listener as witness to both the being and agency of songs and objects would then be to reflect how that listener might be drawn (as I was) to the life of things prior to any authorial intention on the part of the songwriter or singer. While Dawson’s narrative usefully sheds light on the latter, my own would emphasise the former. Before knowing what things do here, we learn that things just coexist in weirdly mundane ways. The song is the frame for this coexistence before it is the vehicle for articulating what things do and what they mean for people.

The foregoing is some of what I wanted to write about Richard Dawson’s songs five years ago. Because it still sums up my response to his music, I’ve only slightly tweaked it to make it relevant for this newsletter. I’ll share some more of the material next week. For now, here are a few additional thoughts that struck me as I prepared this version of the text and thought about ‘Wooden Bag’ and Dawson’s songcraft more generally.

‘Wooden Bag’ is still a standout song for me, both as a music fan and as someone interested in songs and objects. It still feels like a foundational text for what I’m exploring in this project.

Posting this text a week after my post on Iris DeMent’s My Life pointed me to some connections I might not otherwise have made. Writing about DeMent’s album, I mentioned life writing, memory boxes and songs that use verses for neutral description and refrains that deliver layers of meaning and emotion that the verses have been preparing. That is what Dawson does in ‘Wooden Bag’, too, and the wooden bag is a memory box.

I’m struck by some of the comments left under the YouTube video I’ve shared above (‘Wooden Box’, Blank Session). People mention their own ‘Wooden Bag’ moments, which fit nicely with what Dawson and I have both said about the translatability of quite specific objects and memories. The comments about the Newton-by-the-Sea example also came back to me when reading the following in Loudon Wainwright III’s book Liner Notes later on: ‘Everybody has pretty much the same gory details, which is why autobiography, and art, for that matter, work.’

‘I Can Feel It in My Molecules’: as well as being, in my opinion, a fantastic song lyric, this phrase also works as a pointer towards materiality beyond the wooden bag and its contents. The singer is an object, too, a bundle of molecular stuff that thinks and feels and sings and is at one with, while also separated from, the material world around them. And the music that comes out of all of this is material too, sound molecules that affect anyone in their vicinity. As listeners, we attune to the vibrant matter of the song, the singer, and all those objects that they (and we) call to mind. This reminds me of a text that was being used a few years back to promote Dawson’s shows. I’ve seen it in several places; this version is copied from a show I went to see in Newcastle: ‘Rising up from the bed of the River Tyne, a voice that crumbles and soars, steeped in age-old balladry and finely-chiselled observations of the mundane, Richard Dawson is a skewed troubadour, at once charming and abrasive.’

During another interview I did with Richard Dawson, for the 2022 Tusk North Festival, Richard reminded me that he sees ‘Wooden Bag’ as a turning point in his songwriting, one that helped him move away from what he calls the more ego-driven ‘woe is me’ kind of material that typified his earlier attempts at writing. He feels that The Magic Bridge presents a combination of inward-oriented personal tracks and new experiments in trying to look outward.

That outward look would develop at a steady pace over the subsequent albums. I’ll come back to some of that material in my upcoming posts, underlining how Richard Dawson has tried to stake a commitment to the subject matter he works with, whether that means doing justice to people whose stories have been left behind in historical archives or issuing a state-of-the-nation address steeped in keen, nuanced observation.

I haven't heard of Richard Dawson, but listening to 'Wooden Bag,' and knowing your love for Callahan (and Townes), I can totally see why he is one of your faves. He has that quirky, perceptive, and strange approach to how he tells the story (judging simply on one track, mind).

I am sure you are a big fan of Daniel Johnston. Are you familiar with Michael Hurley (who now lives in Oregon)?

Interesting read, Richard, thanks. Haven't heard of this laddie before, will definitely check him out. You mentioned George Perec, one of my literary heroes. Love him. His novels can be a bit daunting, Life A Users Manual and A Void in particular, but as you know are well worth the effort. Readers of your post might be interested in his volume of essays, compiled by John Sturrock, called Species of Spaces and Other Pieces, wherein (as the blurb states) he 'contemplates the many ways in which we occupy the space around us, [and] depicts the commonplace items with which we are familiar in an engrossing, startling way' - chiming with the subject of your piece perhaps. It's a wonderful collection, endlessly fascinating, a book I have enjoyed for many years, my dog-eared edition a constant companion on my travels.

Now, I'm off to investigate this Dawson fella.