In late April of this year I saw Richard Dawson and a group of four other musicians perform most of Dawson’s 2022 album The Ruby Cord at The Playhouse in Whitley Bay. It was an amazing show, not least for the spellbinding rendition of The Ruby Cord’s opening track ‘The Hermit’, a song that runs to over 41 minutes on the album.

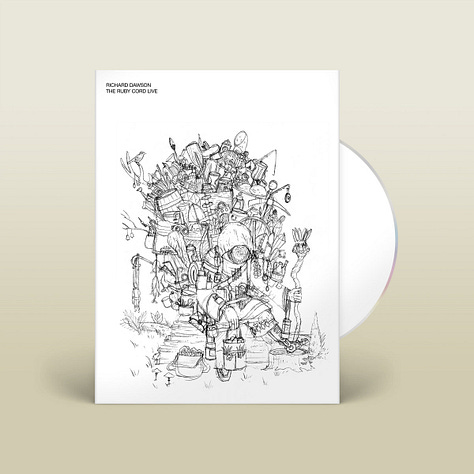

Another show from the same tour was filmed and has now been released as a DVD, catching Dawson and the group—Andrew Cheetham on drums, Angharad Davies on violin, Rhodri Davies on harp and Sally Pilkington on keyboards—at a show in Bristol. Watching the film, I’m reminded of a series of events in reverse chronological order: the Whitley Bay concert in April and some of the thoughts I had at the time; my first forays into the world of The Ruby Cord in late 2022; and the showing of James Hankins’ film of ‘The Hermit’ at Newcastle’s Star & Shadow Cinema, at which I collected my vinyl copy of The Ruby Cord.

Richard Dawson (‘of Newcastle upon Tyne’, as the cover of The Ruby Cord helpfully reminds us) is one of my favourite songwriters and an artist whose work I’ve been following since a now-unrecalled point between the release of his first and second albums of songs (that is, 2005’s Sings Songs and Plays Guitar and 2011’s The Magic Bridge).

I’ve had the pleasure of interviewing Dawson on a couple of occasions. The first time, in 2019, provided material for an academic article about what I call ‘object-oriented songcraft’. It was accepted for publication back in 2020 but the journal for which it was written has yet to appear (hopefully it won’t be much longer). Some of this material made its way into an episode of the Songs and Objects podcast and I may post a text version of that episode in the newsletter in the new year.

The other interview was for the 2022 edition of the TUSK North festival, at Newcastle’s Lit & Phil. That interview was filmed and is available on YouTube. It intrigues me now to realise that The Ruby Cord had been written, performed and recorded at the time of that second conversation but, as the album was not scheduled for release until later that year, my most recent references were to the album Henki (which Dawson recorded with the Finnish rock band Circle) and to the slew of online releases that Dawson had made with Sally Pilkington under the name Bulbils.

During the Whitley Bay performance of The Ruby Cord, I decided I wanted to try and write about the album, especially ‘The Hermit’. It struck me then, and still does now, that this might be a tricky endeavour. Where to start? Which of the many things it sparked in my mind should I pay most attention to and which should I try to ignore? I started a list and then put it aside for several months. When I heard that a film of one of the concerts was going to be released in December, I decided that this would be the point I’d start to work on the list. I watched the film of the Bristol show (directed, like the video of ‘The Hermit, by James Hankins) and, inevitably, the list of things I wanted to think more about grew. Putting those lists together, I now have the following:

The unusual words to be found in The Ruby Cord’s songs, and especially in ‘The Hermit’. This is a distinctive aspect of Dawson’s songwriting and unlikely vocabulary has featured on most of his albums. Sometimes, as on The Ruby Cord and 2017’s Peasant, this is an otherworldly vocabulary consisting of words that most of us don’t hear very often in our daily lives, either because they are technical terms or because Dawson has invented new ones. Sometimes, as on The Magic Bridge, Nothing Important (2014) and 2020 (2019), the strangeness of the words comes form their everydayness and the fact that they’re just not the kind of words we’re accustomed to hearing in songs for that very reason. In the object-oriented songcraft article and podcast, I spoke about the everyday weirdness of hearing songs about ‘Phillips-head screwdrivers, bars of Highland Toffee, Woolworth’s price stickers, trolleys and snooker cues’. The task now would be how to respond to songs that contain lyrics about clarts, clavigers and cleaves.

Video games, wor(l)dbuilding and open worlds. Dawson has spoken in several interviews about the influence of video games on his work. In particular he has mentioned the experience of being in open world game scenarios such as those found in Skyrim. There are avenues to explore here around songwriting as worldbuilding and about songs as games and games as songs. Worldbuilding in song relies on wordbuilding and tunebuilding and, for recorded work and live performance, soundbuilding. To join a song is to enter a world and take on a role (writer, singer, producer, listener, other). A very long song like ‘The Hermit’ makes this particularly evident, but it would be true of shorter songs too.

Connected to this, the desire to join the world of the song, to live in it and spend time within it. I look forward to my visits to ‘The Hermit’ just as I look forward to my visits to Skyrim or the time I spend in Skellige as a Witcher. I know that I am not going to put the song on in the background while doing something else, unless it’s something intimately related to the song like reading the lyrics (‘please read along’, says a message on The Ruby Cord’s inner sleeve) or watching James Hankins’ films of ‘The Hermit’. I know that I’m putting 42 minutes of time aside to spend with this work. When I’m away from it I may even miss it and wish to return. To move between the world of ‘The Hermit’ and the world where I spend the rest of my time is to be very aware of a boundary-crossing. Dawson himself has said something similar about sometimes not wanting to leave the open world of the video game for the ‘real’ world and has also suggested that the real world is scarier and more surreal than its virtual counterparts. The song exists in my head, too, and emerges at unexpected moments, reminding me of its equally unexpected catchiness.

Repetition and refrain. With very long songs such as ‘The Hermit’, it can take some time for a listener to get a sense of the structure of the song and the routes it takes on its journey. Dawson’s songwriting is often characterised by a playful (but also very serious) tension between traditional structures (verses, choruses, refrains, bridges) and what initially sound like more improvised and exploratory forms but which, in fact, are often the result of a formal structure and symmetry that reveals itself on increased familiarity with the song. Repetition doesn’t appear to be an obvious feature of ‘The Hermit’ initially but becomes ever more evident as the song progresses and patterns emerge.

The song concludes with a refrain that does for the entire song what a refrain often does for a verse; indeed, it is tempting to think of the five repeated lines that dominate the last twelve minutes of ‘The Hermit’ as refrains that could have been distributed throughout the song but have been saved up to provide greater release or resolution to the long narrative. This effect becomes even more compelling in the live version with new harmonies added.

Song as speculative fiction and role playing. The function of the first person narrative. There’s no sense here that songwriter or singer is the ‘I’. Why is that still relatively unusual in popular song? Why do we want to conflate the singer, songwriter and public persona? What do we think we are finding out about the artist when we hear song as confession? And how does thinking of songwriters and singers and listeners as putting on personas and playing roles allow us to find out different things? Here, The Ruby Cord should be placed alongside the recent work of another brilliant Newcastle-based songmaker: Me Lost Me’s RPG. That’s definitely a connection I want to return to.

Related to personas, roles and the contested ‘I’, I want to remember that, however many interpretations I or others might offer for these songs, none are true or definitive. As for the songwriter’s meanings or intentions, these can be useful to weave in if they are a matter of public record and if they inform other readings either by confirming them or contradicting them. I have enjoyed conducting, reading and listening to interviews with Richard Dawson and find him a brilliant commentator on his own work and that of others. At the same time, I’m still a follower of Roland Barthes and ‘the death of the author’. I believe in the relative autonomy of the song text from its author and in the meanings brought to the song text by its listeners. I suppose I can believe it even more when I know that the author authorises me to! None of which means that any particular listener, especially me, is ‘right’ and I reserve the right to disagree with or dismiss as many exegetic comments on sites like Genius as those I agree with or learn from. It’s not anything goes but what convinces.

The bringing together of multiple musical styles that have informed Dawson’s work. This is potentially a ‘biographical’ point (and therefore a challenge to ‘the death of the author’ theory) but only inasmuch as it’s biography of the body of work that this is part of: unaccompanied folk singing; free improvisation; rock; multi-voiced refrains.

And what might Richard Dawson’s work tell us about the long and tangled history of prog rock? Or what insights might we gain into his work by considering it in the lineage of prog? In interviews, Dawson has generally downplayed any influence or even awareness of the kind of progressive rock bands that listeners might connect him to due to the themes of his songs, their scope and ambition, the album concepts, and so on. Yet he is reviewed by magazines and websites that focus on prog and there are some clear parallels.

To talk about prog and Dawson’s thoughts on the ambition and the potential of song (which he has been more vocal about) would not be to critique supposedly simpler song forms or those drawn to them as creators or listeners. Far from it: listen to the tunes Dawson has chosen to cover on radio sessions and in live performance, songs by The Bangles, Roy Orbison or Martha and the Muffins among others. I love that Dawson loves pop; I love pop too. To talk about the potential of song, to think of speculative song as referring to form as much as narrative content, is not to denigrate other choices and possibilities.

Going back to refrains, but thinking of them now in terms of landscape as much as journey. Thinking about ‘The Hermit’, ‘Horse and Rider’ and ‘Ogre’—all songs performed on The Ruby Cord tour—I’m struck by the idea that the refrains that close each song are like turning a corner or cresting a ridge and glimpsing the longed-for destination, which may or may not be home. I listen to these songs and I recall long walks on Dartmoor when I was younger and how good the final destination felt after extended exposure to the wild. Those walking memories themselves are suffused with memories of role playing games, fantasy books, heavy metal, folk music and the melding of real and imagined landscapes. Those were my open worlds.

I want to write about buzz and static, about the turning on of amps and speakers and hifi systems, the placing of needles on vinyl, the tentative strumming of electric guitars, the crackle of electricity and what it heralds. The opening of ‘The Hermit’, the way it hums into life, then makes its speculative way for more than ten minutes before any words are sung. The way this was replicated in concert as the musicians came on to the stage at intervals—first Dawson alone with his guitar, then Andrew Cheetham on gentle percussion, then Rhodri Davies on harp, Angharad Davies shortly after on violin, finally Sally Pilkington on keyboard—the building of tension and texture, the almost-soaring, the settling back ahead of the voice’s entrance. It reminded me of improv gigs, of musicians exploring their instruments and each other, one whole onstage ecology encompassing rapt audience members.

Exploratory music. Listening to the Bulbils releases that preceded The Ruby Cord offers a reminder of the resources building towards that album: not just the melodies that get reused, such as ‘Distant Memories’ on the Bulbils album of the same name (which provides a refrain for ‘Museum’ on The Ruby Cord), but also the exploratory, questing nature of musical improvisation. Such processes remind us of the non-bounded nature of song objects, which can take many different forms and travel in multiple directions. Again, ‘Distant Memories’ offers a telling example. As well as appearing in short form on Bulbils 17: Distant Memories, it also gets stretched and layered across fifteen beautifully droning minutes on Bulbils 35: Vision.

Such exploration could, I think, be connected to what Brian Dillon calls ‘essayism’ in his book of the same name. As well as commenting on notable essayists, Dillon explores the term ‘essay’ itself, tracing its history as a word used to describe an attempt at something. Essays are explorations, journeys that set out from a point of enquiry but can take unexpected paths and detours, not burdened by the need to be comprehensive or to close things down. Rather, they offer openings to further possibilities. That does not mean that they are without form or structure but they may well lead readers to wonder, and preferably in positive ways: ‘How did we get here from there?’ When Dillon writes, ‘The “I” travels out from the seat of consciousness and dissipates itself at the extremities’ in the essay, I wonder how this might work for the ‘I’s we find in songs. And I find myself thinking that Richard Dawson offers some excellent examples of such travels, especially in songs like ‘The Hermit’. Dawson as an essaying subject, then, would be another direction to follow, as would the journeying of the I (and the eye) in The Ruby Cord.

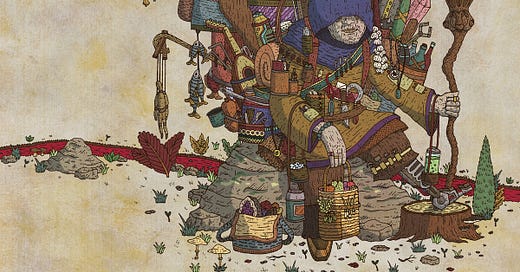

The artwork for The Ruby Cord by Jake Blanchard might inspire another piece, as would Hankins’ films of course. But just as these two artists have provided visual accompaniment to the record and its live performance, so too do the song lyrics focus on the visual through their repeated references to virtual reality, magnification, the formation of images, scanning, eyes and even the typically Dawsonesque lyrical nod to ommatidia. The first and third lines of ‘The Hermit’ are ‘I'm awake but I can’t yet see’ and ‘The image starts to form of a four-poster bed’. From there to scanning insect eyes is a fairly massive cognitive and conceptual journey in the world opened up by song: how do we get there from here? And isn’t it interesting how some insect eyes, when magnified, resemble speakers?

This list of topics and approaches prompted by the various journeys of The Ruby Cord over the past thirteen months could go on much longer. But there is more than enough to consider here and the time has come to wrap this up for a while. I will have more to say about lists before I return to any of the above. It is listing season, after all, and the year must be listed if it is to have existed.