My Life at Thirty

This is about the Iris DeMent album, and only very briefly about what I was doing when I was 30.

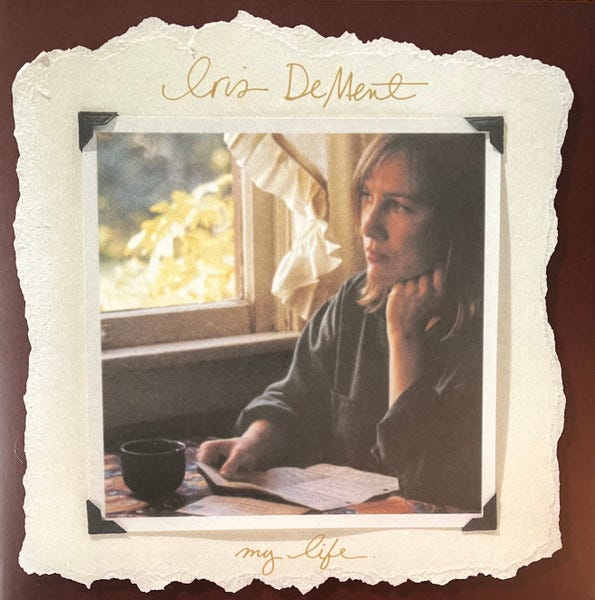

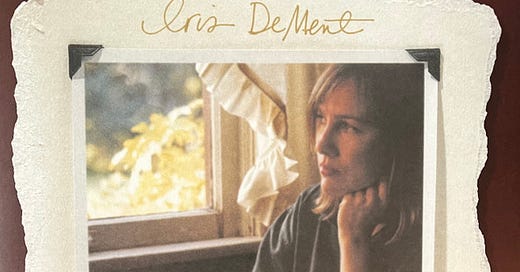

This week, I’ve been spending some time with one of my favourite albums. My Life, the second album by Iris DeMent, was originally released in 1994, and I heard a tape of it not long after. I later bought the album on CD and it’s been a mainstay for me ever since. A thirtieth anniversary edition recently appeared on vinyl, allowing me to welcome the album to my record collection.

Whatever the format, these remain some of the most beautiful, and devastating, songs I’ve ever heard. What I always come back to is the album as a life-writing project, a collection of shareable moments such as you’d find in a photo album or scrapbook.

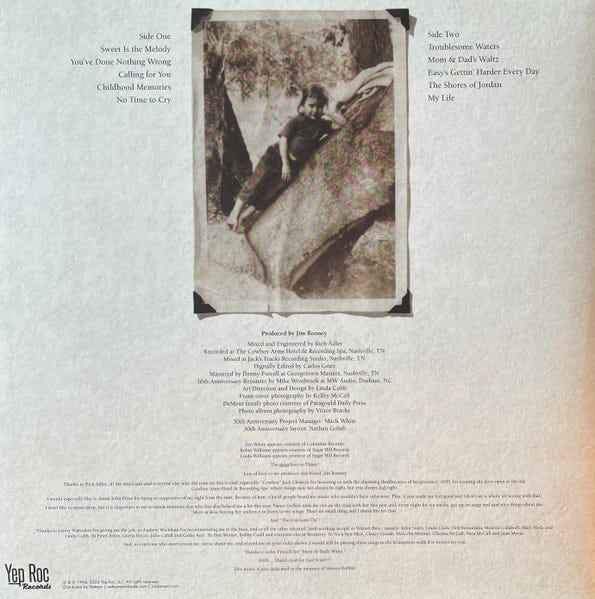

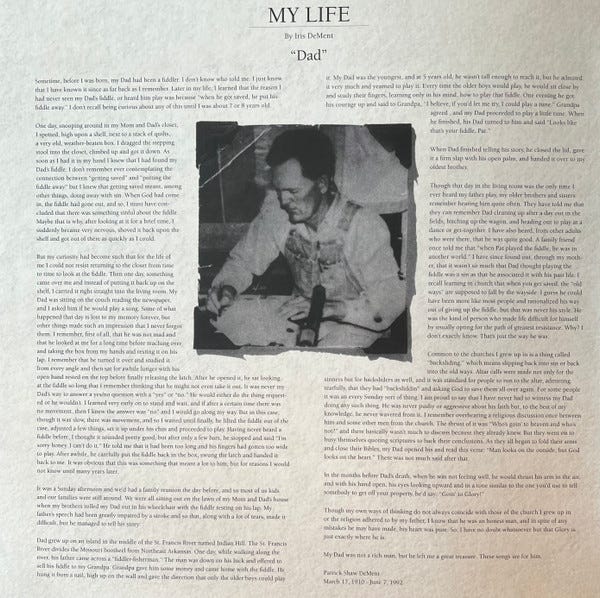

From the visual and textual material on the album sleeves—which it’s lovely to have in large format after all these years—to the song lyrics and dedications, this is clearly material drawn from DeMent’s lived experience. Where her debut album, 1992’s Infamous Angel, had contained a liner note detailing her mother’s dreams of singing at the Grand Ole Opry, My Life comes with an essay simply titled ‘Dad’, a tribute to her recently deceased father and the role of music in his life. A photo of him accompanies the essay, while the colour photo of Iris on the front is matched by a black and white image from her childhood on the rear.

It’s a family album, then. But it is also a remarkable example of how the personal opens portals to the collective, how the viewing of one individual’s photo album or scrapbook is an invitation not only to learn about them, but to place ourselves in their position, to project our own life experiences onto the events and encounters we’re invited to witness. This is, as John Dewey would put it, art as experience.

I’ve always thought there was something timeless about this music, by which I mean not only that it sounded like it could have been made decades earlier, but also that it seemed to exist in, or carve out, a time of its own, a time of reflection. Anyone who’s had the experience of getting lost in old photos, diaries or other personal memorabilia knows this time.

Going through old photos and memory boxes can be a strange, even disconcerting, temporal experience. This is partly because the objects you’re contemplating are dragging you back to your own and other people’s pasts. Partly, too, because the time involved in contemplation is time taken from the present and the everyday, a temporal displacement that can make you lose sense of time and give you a jolt when you return.

I don’t recall reading reviews of My Life at the time of its release, but it was a long time ago and I can’t be sure. Curious as to how the album is documented online, I visited its Wikipedia page and followed a few linked reviews. I enjoyed Greg Kot’s review for Trouser Press:

You could scan the contemporary music horizon for a week and still not hear anything quite like Iris DeMent’s voice, a full-bodied soprano that bursts with yearning and knowing, while suggesting Loretta Lynn’s no-nonsense conviction and Mother Maybelle Carter’s purity.

I’d been curious to see how other writers described DeMent’s voice, a voice I find singular and difficult to put into words. Reading Eric Weisbard’s entry for Spin’s 1994 year-end review, I was struck by his attempt at the sonic textures of the album: ‘preserved twang and suspended orchestrations’. That gets close.

Kot noted another aspect of the album’s out-of-timeness: ‘In celebrating faith, love, rural simplicity and singing along to the country radio, DeMent seems almost too innocent and simple for an ironic and edgy era’. That’s true, but this side of her has to be balanced with the ‘no-nonsense’ side that Kot also highlighted. While there is an innocent, and sometimes sentimentalised, aspect to some of the songs on My Life, there’s also a good amount of cold reality, such as the detail of a baby being found in a ditch in the album’s hardest-hitting song, ‘No Time to Cry’.

When I first heard My Life, I was studying for a BA at the University of Warwick. I remember seeing Iris DeMent performing at the Warwick Arts Centre on the university campus. I can’t find any record of that gig now, but I think it was a tour to promote the 1996 album The Way I Should rather than its predecessor. I do remember how good it was to see those songs performed live, and to see the woman behind that remarkable voice in the flesh.

At the time of my undergraduate degree, music was an obsession that didn’t get explicitly connected to the things I studied: literature, history, film. A few years later, while undertaking a master’s degree, that changed and I began to study and write about popular music, taking the first steps towards a career that I’ve been in for over two decades now. For my final project in 2002, I wrote a dissertation about place, race, memory and experience in US hip hop and country.1 Here is some of what I wrote about DeMent’s 1994 album there:

My Life is almost wholly concerned with the effects of memories and shared experiences. [DeMent] sings about the communal benefits of music in ‘Sweet Is the Melody’, reminisces about ‘Childhood Memories’ and grapples with the responsibilities of everyday life while reflecting on her father‘s life in ‘No Time to Cry’. She also provides an essay about her late father to the liner notes. There is also an evocation of earlier styles of music in the way she performs her songs. The instrumentation she favours could have been used at any point in country music‘s history: acoustic guitar, piano, fiddle, mandolin, upright bass. In her singing voice she manages an ‘old-fashioned’ delivery by singing slightly too loud, seemingly unmindful of the possibilities of microphone technology, in a voice that has been described as both ‘pretty‘ and ‘raw’ and which tends to waver around notes, adding to the air of ‘naturalness’ in her lyrics and instrumentation.

A few too many scare quotes, and I recall being picked up by an assessor for claiming that the instrumental line-up could have come from ‘any point in country music’s history’. Overall, though, I’m satisfied with this summary of the album twenty-two years later. The quoted description of DeMent’s voice as ‘pretty’ and ‘raw’ came from a chapter in Nicholas Dawidoff’s book In the Country of Country, which was a valuable resource for my project.

What follows are thoughts I had as I listened to the album for the first time on vinyl last week. Revisiting a much-loved work like this inevitably brings previous experiences with it, reminders of earlier selves, an awareness that certain words and sounds are embedded in our bodies. But there’s also the chance to discover new things or to find new articulations of things that you may have forgotten or failed to say before.

I’ll include YouTube links to a few of the songs. The album is easy to find online.

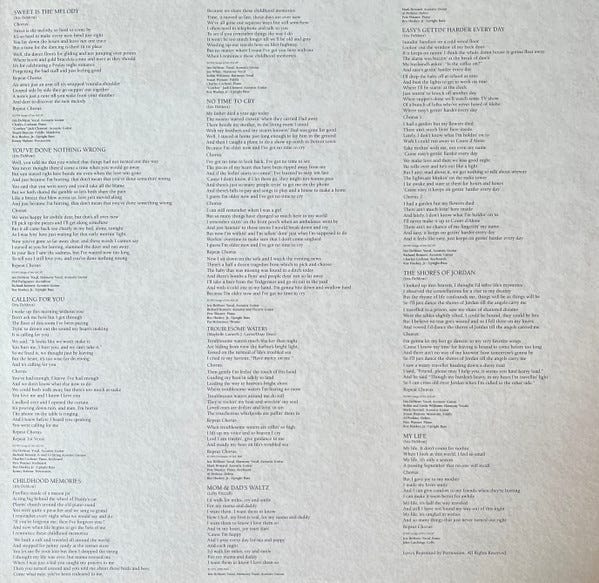

‘Sweet Is the Melody’. A song about songwriting, about finding the words and sounds that are going to be ‘just right’. I say ‘words’ because this is a beautiful lyric, but Iris is mainly singing about dancing tunes here:

An arm’s just an arm till it’s wrapped ’round a shoulder Looped side by side they go steppin' out together A note's just a note till you wake from your slumber And dare to discover the new melody

I’ve always loved the way Stuart Duncan’s fiddle finds the melody at 2:24 and takes flight with it, adorning its wings ever so subtly as he goes. Sweet indeed.

There’s a lovely version of the song recorded for the Transatlantic Sessions, with Iris accompanied by a different instrumental mix.

‘You’ve Done Nothing Wrong’. Opening the album with a song about songwriting was a graceful touch. Now it’s time to get down to brass tacks of romance with the first of two consecutive breakup songs. No matter how many times I’ve heard this song, I always think it’s called ‘That Early Morning Light’ because of how the chorus resolves. Sleeplessness and regret are the keynotes here, It’s not you, it’s me, the song declares, and Phil Parlapiano’s mournful accordion brings the message home.

‘Like a breeze that blew across us, love just moved along’.

‘Calling for You’. A portrait of a moment, where the action and reflection seem to take place in one morning while summoning various other times: a prehistory, a ravaged present, an imagined future. I can’t be sure the time of the final verse is the same morning, because one of the clever things song verses can do is jump us forward or backward in time, showing parts of the pattern that are thematically and melodically connected but distinct. I hear it as the events of a single day, though, and am tempted to describe the song as Carveresque. But where Raymond Carver might leave heightened emotions outside of the frame of his narratives, there’s something too keening and overwrought in this song’s chorus to make this viable. There’s something I often relish in song here, when verses stick with neutral description and choruses bring explicit meaning, consequence or emotional fallout.

‘Childhood Memories’. This gets close to being a list song. Like some of my favourite writers—Jorge Luis Borges, Joe Brainard, Roland Barthes—DeMent places discrete recollections together to recreate lived experience. Of the self-written songs on My Life, this is the only one without a chorus, which adds to the sense of it being an accumulation of distinct memories, each as important as the others.

Because I have different life memories, and because many of the connections I’ve made have been through the music I’ve listened to, I hear the start of the second verse—‘We built a raft and travelled all around the world’—and I think of John Stewart’s ‘Pirates of Stone County Road’, with its kids ‘pulling for China’ on their makeshift man-of-war. And that in turn will put me in mind of David Ackles’ ‘Subway to the Country’ and make me think about other songs that evoke childhood wonder. Such are the memory patterns we weave over a lifetime of listening.

‘No Time to Cry’. This song has a couplet leading to a refrain that has stuck in my mind ever since I first heard it:

Well, I stayed at home just long enough to lay him in the ground And then I caught a plane to do a show up north in Detroit town Because I'm older now and I've got no time to cry

DeMent sings about a daughter (we guess it’s her, at least in part) who is recalling the death of her father a year before and detailing her busy life. Being busy is presented both as something that just comes with life, leaving you no time to reflect or mourn, and as something you choose to do because, as one of the lines puts it, reflection and mourning might just make you ‘come unglued’.

I've got no time to look back, I've got not time to see The pieces of my heart that have been ripped away from me And if the feelin' starts to comin', I've learned to stop 'em fast 'Cause I don't know, if I let them go, they might not wanna pass

This is one of the reasons I call this album ‘devastating’ as well as ‘beautiful’. When I first heard and fell in love with this song, I hadn’t yet lost a parent. I wasn’t hearing it literally in that way. I was just hearing about loss and how one tries to deal with it, and that’s something that can be translated into many situations. There are details in the song which pinch harder since I lost my mother seven years ago, but that’s the way it is with life: joy and heartbreak as layers of the palimpsest, new experiences written over the old, with the older ones still bleeding through. That’s what this song has always been about for me, how that layering of life experience can threaten to overwhelm, and what we do to stop that from happening.

Now that I can listen to My Life as a vinyl record, this song invites additional gravity by being the end of Side One. Listening to it this time around, I think of how this song seems, on the surface, to present a different kind of memory work to ‘Childhood Memories’. In that song, memory is presented as a project or a strategy; remembering is something you would actively want to do, especially as you got older. In ‘No Time to Cry’, memory is dangerous territory you can’t afford to spend much time in. That’s not only because ‘there’s bills to pay and songs to play and a house to make a home’. It’s also because of the emotional cost, how the memory of loss keeps ripping away the plaster.

It’s involuntary memory, the one that Proust wrote about so well, the one that Hoagy Carmichael hymned so elegantly in ‘I Get Along Without You Very Well’, and that other songwriters have evoked in songs that bely the everyday pretences of getting by or getting over. But what did Proust and those songwriters go and do? They wrought beautiful art from painful recollection, turning involuntary memory into deliberate remembrance. That’s what Iris DeMent does too with ‘No Time to Cry’, and that’s why, in the end, it’s not so different to ‘Childhood Memories’. The songwriter has turned painful experience into a beautiful object that she and her listeners can return to repeatedly. This is song as working through.

‘Troublesome Waters’. The first two tracks in Side Two of My Life are cover versions. This one comes from the Carter Family and hymns the power of faith to overcome hardship. I don’t have the faith that the Carter Family had, that Iris DeMent’s family had and that she often seems to be searching for. I have sometimes wished for it, and this song makes me think, again, of what we go looking for to help us get through, to bring us back to port safely. In the past, without the break imposed by the vinyl record, I assumed the sequencing of this song after ‘No Time to Cry’ was supposed to make that theme explicit. The new format doesn’t fundamentally change my mind about that, but there’s more distance between these recorded moments now.

‘Mom & Dad’s Waltz’. This may have been my introduction to this Lefty Frizzell song, though it’s possible I’d already heard it opening Willie Nelson’s To Lefty from Willie. This certainly became the version I was most familiar with, simply because I played the DeMent album more than the Nelson tribute, and I was still some years from diving into Frizzell’s own recordings. I came to love Frizzell, though this song has never been a favourite. I’ve tended to find it too mawkish. But it fits well with the themes of family that pervade Infamous Angel and My Life, so I let it flow by like a breeze that moves along.

‘Easy’s Gettin’ Harder Every Day’. Another quietly devastating song. The instrumentation is sparse, subtle and reassuring: acoustic guitar patterns that resolve frequently, creating a cyclical feel; gently plodding upright bass, unobtrusive keyboards that drift in with the gentlest of churchy swirls from the first chorus. Such is the song’s studium. Bursting out of it to pin the listener to their seat is the punctum of DeMent’s voice: direct, plainspoken, weary, accepting, hurting.

She rattles off the elements of the everyday: buzzing alarm at dawn, husband’s expectation of coffee, hurried breakfast, school run and rushed commute to a job so dreary the song jumps over it to the evening, where the TV brings alienation, lovemaking is desultory, there’s nothing to talk about and not even the comfort of sleep, just staring out the window for hours at the lights blinking on the radio tower.

And rising up in the first chorus, a craving: ‘Wish I could run away to Coeur d'Alene / Take nothing with me, not even my name’. But this hope for something else seems as doomed as the flower garden that died, also recalled in the chorus. The second time around, it’s ‘I’ll never make up to Coeur d'Alene / There ain’t no chance of me forgettin’ my name.’

A song with no hope, then. But a beautiful song, a song that, like so many country and blues laments before it, suggests that the singer will go on and that the song is one way of coming to terms with thwarted dreams.

By the time I came to write about Iris DeMent in the early 2000s, I was living in Portugal and had learned a new word for the bittersweet paradox of longing turned towards pleasure, or the seeking of pleasure in sadness: saudade. And I’d learned a new musical expression for engaging with fate and for singing as a way of working through: fado. ‘Easy’s Gettin’ Harder Every Day’ is, for me, Iris DeMent’s finest fado.

‘The Shores of Jordan’. A song about fate, to continue a theme. The biblical imagery is back, bringing echoes of ‘Troublesome Waters’ and the church-inspired directness that is a hallmark of so much of DeMent’s lyrical, melodic and vocal work. ‘The rhyme of life confounds me, things will be as things will be’. But, again, not quite, because the singer is directing things, is making us feel the way she wishes to make us feel, is making us feel better for a while.

‘My Life’. And that—making us feel better for a while—is the payoff in the title track, sequenced expertly to close the album with a dialectical note that, we realise in retrospect, has been present throughout.

My life. It don’t count for nothin’ When I look at this world, I feel so small My life, it's only a season A passing September that no one will recall

There it is again, that fatalism, that sense of worthlessness and thwarted possibility. The second verse ramps up the existential doubt: a life ‘half the way travelled’ with no ‘way out of this night’, ‘tangled in wishes’. It’s crushing. But where the chorus of ‘Easy’s Gettin’ Harder’ offers no lyrical comfort, just the balm of that beautiful voice and melody, ‘My Life’ recognises that the presence in others’ lives is both an ordinary and an extraordinary gift:

But I gave joy to my mother I made my lover smile And I can give comfort to my friends when they're hurting I can make it seem better for a while

Even if it’s only the briefest of illusions, I’ll take it. DeMent’s piano intro alone is enough to make me feel better, to remind me that I’m about to hear a song that has walked through my life, as Guy Clark might have said, like a coat from the cold. On this listen, I’m reminded, too, of the perfectly pitched ornamentations from John Catchings’ cello, first as plucked strings, then gorgeous bowing.

I don’t know what these songs will mean to me in years to come. I can’t imagine they will ever be too far from my thoughts, especially when I think about transience, memory work, passing Septembers and life writing, or when I need to hear a voice with the particular tone of firm compassion that Iris DeMent provides.

I’ve enjoyed spending time with My Life again, and thinking about my life too, but not obsessively, nor in a way that would stop me from doing the things I need to do. I know that temptation only too well. Sometimes it’s enabled me to do some necessary memory work, whether for the purposes of writing or just to work some things through. Other times it’s taken me too far into the rabbit hole: too much reflection, loss, regret etched into the traces of what a life leaves behind.

Sometimes memory boxes need to remain closed, but it’s been such a pleasure to open this one again.

The dissertation is available online at Academia.edu. Incidentally, I’ve titled this post ‘My Life at Thirty’ to reflect the album’s age. But my life at thirty involved writing my master’s dissertation.

I’ve kept on thinking about this since I read/listened to it yesterday. First, thank you for it! Second, I can’t decide how I feel about the My Life song, which I had heard for the first time. That is, whether I believe, for myself, that things that the song lists are enough. I did an essay asking a similar question to the question the song asks, and thought that maybe I had reached some conclusions, but this reminds me that it all stays open, somehow. A rich article, thank you.

Great read that makes me very interested in this artist and album (I am unfamiliar with both), Richard.

A box with photos, letters, memories of the people we once were or always were but lived different lives in different times, and we all looked a bit different back then. I can relate to that. There are some memories I am happy to keep in a box, whilst others I reflect fondly on. Music can definitely trigger and unleash many memories and emotions.