Patterns, Loops and Connections

Not a review of Laura Marling's new album, but some things it got me thinking about. Another piece built from fragments and connections.

For the last week or so, I’ve been listening to Laura Marling's gorgeous new album Patterns in Repeat. My current earworm songs are ‘Child of Mine’ and ‘No One’s Gonna Love You Like I Can’, though that might be partly driven by the early availability of these tracks, both of which had already been added to my ongoing 2024 playlist prior to the album's release. Increasingly worming their way in are ‘The Shadows’ and ‘Caroline’, two exquisitely crafted songs I might once have described as ‘Cohenesque’, but which I have learned to think of as ‘Marlingesque’.

But it’s the two songs that provide the album's title—‘Patterns’ (on Side A) and ‘Patterns in Repeat’ (on Side B)—that have been most on my mind and got me thinking about patterns, loops, repetition and connections, topics that I encounter frequently when reading and writing about songs and objects.

What follows is not a review, or close reading, of Patterns in Repeat (the album, the songs), nor is it about Marling's brilliant songwriting. It's about some patterns that emerged as those songs accompanied me during the course of a week.

Pattern recognition is one way we make sense of objects. It's how we distinguish and categorise. It's how we are categorised by other humans and non-humans, and by machines. It’s how Spotify Discovery or Release Radar works, how you see what you see in your social media feeds. It's in part how you decide what art you love, and how that love is decided for you. It's how we make connections, how we repeat, how we learn, forget, move on or away.

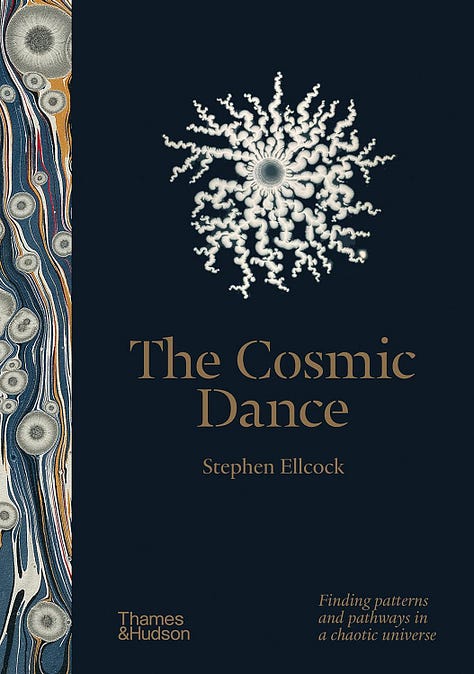

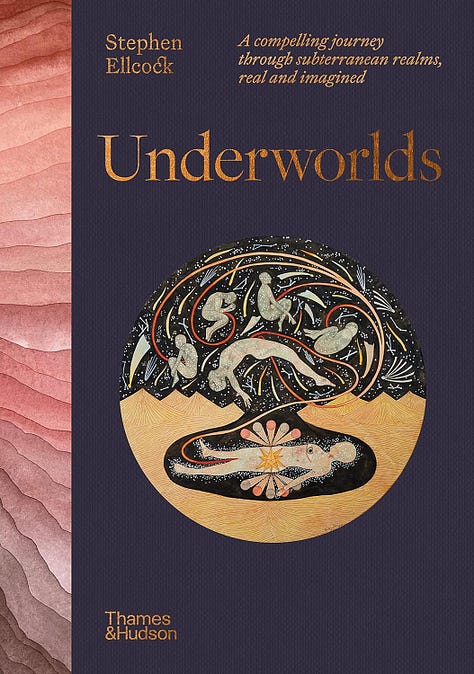

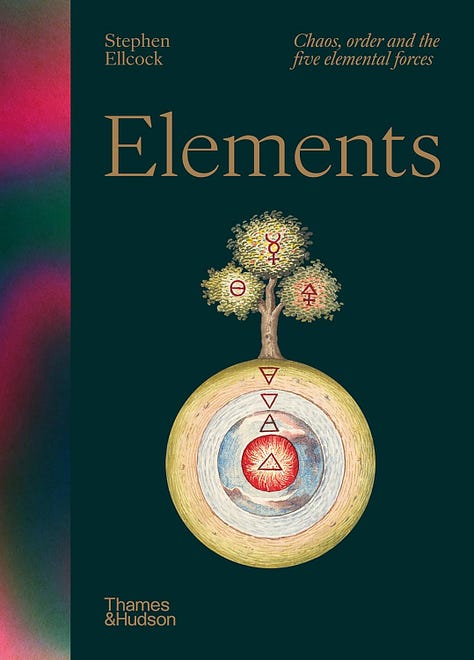

I’m an admirer of Stephen Ellcock’s books and online galleries of weird and wonderful art and objects. His latest book, Elements, provides a brilliant follow-on to The Cosmic Dance (2022) and Underworlds (2023). I’ve been dipping into it in the same week I listened to Patterns in Repeat. As I get to know it better, I’m sure it will introduce me to new patterns and repetitions from the visual archives that Ellcock weaves together.

In The Cosmic Dance, Ellcock describes his work as the result of ‘a lifelong … obsession with the power of imagery, symbol and pattern’ and as an attempt ‘to re-engage with a world in which connections count and the occasional escape route still exists’.

I’ve always looked for, and followed up, connections between the things I encounter in life, especially in art. I’ve often felt I was seeking a pattern each time I followed one song or book or film or painting to another, something that would finally confirm WHAT IT ALL MEANS. But, of course, the pattern was always changing. There's no final, magical piece that would make it all end, make it all make sense. The pattern changes while making you think it hasn't. That’s something that an artist like Escher (an early favourite of mine) makes clear; it’s also something that music’s modulations underline for us repeatedly.

What would music be without patterns in repeat? Laura Marling's guitar figures; the electronic textures that occasionally bleed through her otherwise stripped-back album; the verses, melodies and refrains; the repetition-with-variation of key songs such as ‘Patterns’, ‘Patterns in Repeat’, ‘Lullaby’ and ‘Lullaby (Instrumental)’; the importance of lullaby as pattern (setting the pattern of sleep, setting sleep as a pattern); how we fall into patterns of behaviour; how we’re subject to genetic patterns in repeat, to variations, to copies of each other and mould breakers; the ways we’re trapped in destinies and escape from them: all of this and more is thematised and brought to sonic life on Patterns in Repeat.

But, as I said, this isn’t a review or reading of that album alone. You’ll find musical patterning in all music and, when you don’t, you’ll know it by its absence. You’ll find patterns and repetition as themes in many lyrics, too. Marling isn’t alone here, but she’s hit on some fantastic ways to explore the topic and to get her listeners thinking of it in relation to their own lives.

Heading after musical patterns I’ve loved of late, I put the needle on ‘Aey Nehin’, the first track from Arooj Aftab’s divine Night Reign. The repeated and modulated loops created by the harp and guitars on this song exemplify, for me, the ways musical patterning can entrance.

I’m reminded of the questions posed by Lynnée Denise in the liner notes to Aftab’s album, one of which is ‘What patterns and pieces will break open the night mind’s path?’

Just as readily, I think of the many times I’ve picked up on patterns, repetition and loops in electronic music. It’s not an area I’ve written about much in this newsletter, focussed as it is on songs with lyrics. But electronic music—whether of the Deutsche Elektronische Musik type, or the ‘ambient’ style exemplified by Aphex Twin’s recently reissued Selected Ambient Works Volume II, or EDM—remains one of the main ways I reflect on musical form. The last book I wrote was about the kuduro-inspired batida (beats) produced by Afrodiasporic DJs in Lisbon. To paraphrase Lynnée Denise, this was music that got me thinking about patterns that would open paths for the mind and body.

Listening to some of these recordings is like playing one of those stereo demonstration records from the 1960s: the focus is on sound per se, its location, what it does to perception. Batida tracks are as much about what happens to your head as to the rest of your body. There is an invitation to enter the loop, which exists as both an ever-present insistence and also as a kind of void, the kind that opens up in trance-based music to allow the trancing body–mind to reach the desired level of engagement. Looping, while seeming like perpetual motion, can also become a kind of stasis, while occasional glitches serve as reminders of the imperfections of loops, of how repetition messes with the mind to create new patterns.

—DJs do Guetto, p. 67.

And here’s what I wrote about a couple of the tracks on the DJs do Guetto compilation from 2006, along with the tracks themselves:

Remembering the oddness that attends the constant repetition of a single phrase (a strategy used by many sound artists keen to mash up their auditors’ distinctions between sound and sense), we can listen in and out for that nonsense moment when an everyday sound morphs into a block-rocking beat. DJ N.K.’s ‘Alarme Noturno’ works well for this, scooping out of the everyday annoyance of the neighbourhood alarm an undeniably brutal but catchy loop that pitch-shifts its way into acid rave trance by way of bleep techno.

Then there’s Fofuxo’s ‘É Africa’, in which a repeated vocal sample moves into an echoey dubby break each time the beat pauses, while a minimal melodic bleep pans left and right to evoke an acid daze. Fofuxo constantly teases the beat towards something more developed, something like an ecstatic soul-based house track, only to draw back to the beat and the repeated ‘é Africa’ vocal sample. The track’s title, meanwhile, like many from Lisbon batida, evokes the Black Atlantic and its looped movements and histories, a reminder of the loops within loops that uprouted musics reflect and create.

Since I started keeping notes on songs and objects, Mark Booth’s 1983 book The Experience of Songs has been a constant touchstone. Booth often refers to song in relation to patterns. In chapter 3 of his book, he discusses folk ballads in terms of architectonics, memory practices developed through oral culture, and work in consciousness studies and psychology on left and right brain activity.

The presence of musical pattern makes song, among the various kinds of verbal artifacts, the most distinctively time-patterned form. Even if hidden chiastic or other structures lurk in folktales, for example, the ballad that shares those patterns is higher up on the ladder of ordering patterns over time, because it adds together the short-range patterning common to all versification, the long-range patterning of skillful oral construction, and the intermediate-range patterning of shapely melody.

—Mark W. Booth, The Experience of Songs, p. 66.

Booth cites research that suggests songs can be recalled as wholes (though I would think of what we might call ‘song chunks’ as the ‘immediately’ recollectable units, which help us to construct whole songs) in a manner not possible for a passage of writing or speech (unless, presumably, that passage already lent towards song in some manner, such as the words of gifted orators who use song-like devices as part of their speeches).

Booth refers to a ‘static’ quality of song that allows it to be graspable. I think we might think of ‘return’, ‘repetition’ and ‘continuity’ in similar ways: these features in song allow us to grasp the object. ‘The static quality’, Booth writes, ‘has to do with song having been shaped into musical pattern, and perhaps further patterns, not dependent on time—a fixity, that sounds in time move to fulfill’.

‘Song pattern is an apparent victory over time’: Booth again. This is a useful observation, not least for the way it challenges much of what I’ve written before on the ability of the mind and recording technology to fix something (such as a song) that was in danger of being lost. The revelation here is that song is already doing that fixing, that song itself is a technology of memory. ‘[I]t is of the nature of song in general to stand still … A recorded song is a grasped chance for the owner-listener to seem to escape from time’.

Work out the patterns of your favourite pieces of music and they will tell you something about yourself. Don't fall into the trap of thinking those patterns are universally recognised, rejoiced or rejected.

Of course, when you start thinking about patterns, you see them everywhere, and everything becomes a pattern in repeat. It’s like when I wrote about leaves and mud, and everything became leaves and mud for me. Now I look through old photographs and I note again my penchant for capturing life’s patterns.

When I think of leaves as patterns, I switch between an intense focus on the structure of an individual leaf to thinking about leaves as patterns on a tree, to trees as patterns on a landscape. Machines can take us further at both ends of this spectrum: cameras, microscopes, drones, aeroplanes.

Another book I’m currently reading is The Ghost Theatre, a novel by Mat Osman. I picked it up last month in a store in Penryn, having made a connection to Stephen Ellcock’s work (Ellcock and Osman collaborated on the book England on Fire) and, via a memory from longer ago, to Osman’s involvement with Suede.

Birds play a crucial role in The Ghost Theatre and there’s a great passage in an early chapter where Osman describes the sonic and visual patterns made by birds.

And birds. Everywhere birds. The sound hit you first: vast waterfalls of birdsong, overspilling like a treasure hoard. On first hearing it was a thick braid of noise but as your ears grew accustomed your ears picked out individual songs. The padded ruffles of wood pigeons and the stream of wren song. Sparrows bickering across the music-box tunes of the great tit. Blackbirds moaned and there was something human to their tone, as if they might break into speech if they so wanted. There were complex helices of melody, surely too ornate for one delicate throat to produce. Cheeps and burbles, warlike caws, lovers’ coos, flutters and warbles. Flutes, whole orchestras of them, bassoons, hand drums and viola screech. And then, when the air was too full, bursting with song, you raised your eyes to see a sky seething with birds. Unconstrained by human patterns, their paths were crazy, crazed, cracked.

—Mat Osman, The Ghost Theatre, p. 41

I love that metaphor of ‘a thick braid of noise’, sounds woven together, a pattern that impresses first as a whole but which invites the teasing apart, or at least the recognition, of its constituent threads. I think of days spent in the garden or the countryside recently where, ignorant and curious about the bird song I’m hearing around me, I reached for the Merlin app on my phone to try and identify the voices coming through the braid.

It’s not always a thick braid—I’m rarely surrounded in my day-to-day by the number and variety of birds described in Osman’s passage above—but it’s a reminder of the ways that sonic patterns can be interpreted and represented by machines.

That gets me thinking about algorithms again and how our listening behaviour feeds directly into music discovery.

I think, too, about how we become parts of bigger digital patterns. It’s a topic explored by John Cheney-Lippold in the book We Are Data: Algorithms and the Making of our Digital Selves. As well as exploring visual patterning, such as facial recognition software, Cheney-Lippold mentions how machines can learn through sonic and gestural patterning. He tells the story of a ‘marimba-playing automaton’ named Shimon, who has been programmed to play, and to play along with (improvise) jazz:

With four mallet-hands, a long, lamp-like neck, and softball-sized head, the robot hunches over a four-octave wooden marimba and starts to move. Its head nods to the beat, even closing its camera-lens eye to imitate both a blink and immense concentration. A human bassist sits to its left, a human keyboardist to its right. All three players improvise a song, in real time, that evolves over time. The music slows, becomes more syncopated, or even shifts keys. The robot can be programmed to play like you or to follow your lead an accompany you. And the robot can also be told to play like John Coltrane or Thelonius Monk. It can even play like a percentaged buffet of all three (‘Coltrane,’ 25 percent; ‘Monk,’ 25 percent; ‘You,’ 50 percent.

—John Cheney-Lippold, We Are Data: Algorithms and the Making of our Digital Selves, p. 67-8.

Furthermore:

‘You’ is a constantly evolving rendition of self, an undoing and redoing of hidden patterns that Shimon perceives from your playing. These constantly recalibrating models of ‘you’ generate a new aesthetic form, one dependent on musical inputs but also reflexive to how those inputs change.

—Cheney-Lippold, p. 69

Cheney-Lippold moves from these descriptions to a critical reflection on what all of this means for the cultural politics of jazz; I think there are interesting things to note for the cultural politics of imitation, too. I won’t go into that here, but I imagine that the concerns raised in We Are Data are shared by many who reflect on everything (and everyone) becoming digital information.

At the same time, I continue to wonder whether there’s something in musical patterning that has always leant itself to this kind of generative process, whether, as I asked last year in a post about the song ‘Jolene’, music has always been a form of artificial intelligence. To quote from my conclusion to that post:

Songs as recordings … are examples of the infosphere, of how things can become non-things. All those versions of ‘Jolene’ out there, available to many of us via a few clicks, are all just so much information. It’s no wonder that bots are being trained to feed off online tracks and to create fake new tracks that spread like viruses though the infosphere.

…

This is all part of the discourse prompted by nonhuman songholders. If music predicts the future, as theorists like Jacques Attali have argued, then it’s not so a much a question of whether nonhuman songholders could really operate without some kind of human involvement (whether at the production or consumption end), but rather of how so many musical examples make it so easy for us to imagine such a possibility.

Go back to those patterns from your favourite pieces of music. What is there in them, or beyond them, that would challenge the idea that everything is replicable data? What escapes patterning? Find that and you might learn something else about yourself.

Osman’s novel also got me remembering the times I’ve witnessed murmurations of starlings. Ones that stand out in my memory are those over Brighton Pier during the years I lived on the Sussex coast and one near Marazion in Cornwall in December 2016. I think the latter has been on my mind partly because I was in Marazion again last month, and partly because I remember that murmuration being the cause of a family outing during a post-Christmas visit that is special to me for several reasons.

As is my wont—always wanting to make connections, find patterns!—I went in search of photos from that trip. I eventually found some and was reminded that I’d actually not managed to capture the event well due to a combination of low light, a smudged lens and user incompetence. That said, I quite like the way the birds blur into the brooding cloud formation.

That photographic search brought up many more instances of patterning, of course.

This showed me not only that I have long been drawn to capturing patterns in my immediate surroundings, but also that this pursuit is itself a pattern, a set of behaviours that I’ve repeated over and over through the years.

So I shouldn’t have been surprised when, having taken a photo of some fallen leaves I’d picked up in the garden and placed in a metal bin the other day, I then found a photo I’d taken a year before of fallen leaves I’d picked up from the garden and placed in a plastic bin.

I had no recollection of taking the 2023 photo, but I know myself well enough to know this kind of repeated pattern is very common. I often encounter something similar with ideas I have when researching and writing. I go to log them so I don’t forget them, and find I’ve logged pretty much the same idea at some point in the past.

Another consolidation of the digital self through patterns of behaviour. How much of a life could be reconstructed from such repetitions?

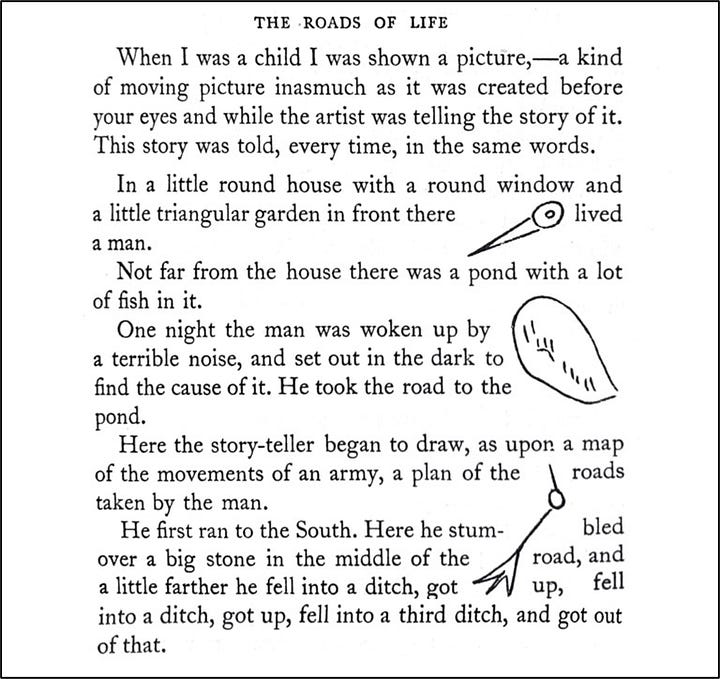

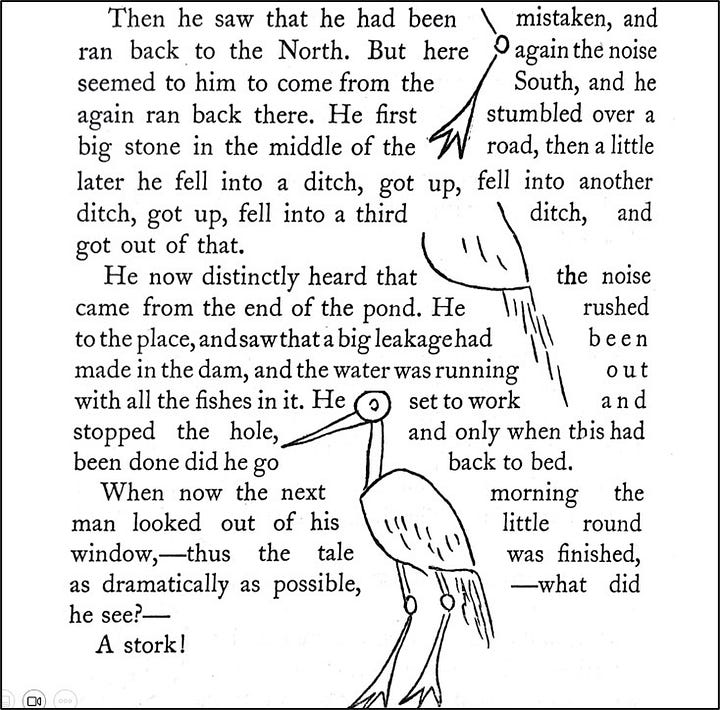

In Out of Africa, Karen Blixen includes a chapter called ‘The Roads of Life’, within which she tells, and illustrates via a crude map-like diagram, the story of a man who, having been woken during the night by a loud noise, stumbles around his garden trying to find its source. After several failed attempts, marked on the diagram by the directions he took and the obstacles he found, he finds a leak in one end of the garden pond, fixes it, and goes back to bed. On waking the next day, he finds his nocturnal activity has left behind the pattern of a stork in the garden.

In summarising this already quite short story, I was tempted to use not only a scan of the text as it appears in Out of Africa (above), but also Adriana Cavarero’s neat retelling at the start of her book Relating Narratives. For a start, I think Cavarero summarises better than I do; what’s more, having read her summary, I found it difficult to come up with one of my own that would be different. I will turn to her for an additional detail, not yet related, that Blixen adds as a kind of moral and which undoubtedly influenced my earlier question about what the evidence of my collection of photographs might say about the patterns of my life.

At this point Karen Blixen asks herself: ‘When the design of my life is complete, will I see, or will others see, a stork?’ We might add: does the course of every life allow itself to be looked upon in the end like a design that has a meaning?

…

The meaning that saves each life from being a mere sequence of events does not consist in a determined figure; but rather consists precisely in leaving behind a figure, or something from which the unity of a design can be discerned in the telling of the story. Like the design, the sory comes after the events and the actions from which it results. Like the design—which is seen only at sunrise from the perspective of whoever looks at the ground from above without treading on it—the story can only be narrated from the posthumous perspective of someone who does not participate in the events.

—Adriana Cavarero, Relating Narratives: Storytelling and Selfhood, pp. 1-2.

Another new book that places pattern at its centre, and that does so by reading present evidence to tell stories of the past, is Richard Dawkins’ The Genetic Book of the Dead. Dawkins sets his stall out in a chapter entitled ‘Reading the Animal’:

You are a book, an unfinished work of literature, an archive of descriptive history. Your body and your genome can be read as a comprehensive dossier on a succession of colourful worlds long vanished, worlds that surrounded your ancestors long gone: a genetic book of the dead.

—Richard Dawkins, The Genetic Book of the Dead: A Darwinian Reverie, p. 1.

This is clearly a much longer history than the one Blixen was contemplating in ‘The Roads of Life’, and one more in service to pre-determined patterns. I can see why, from one disciplinary perspective, Adriana Cavarero, riffing on Blixen’s take, would emphasise that ‘Every human being is unique, an unrepeatable existence, which … neither follows in the footsteps of another life, nor repeats the very same course’ (Cavarero, p. 2). And I can equally see why, coming from another direction, Dawkins would underline the evidence of deeply embedded patterns and histories, of ‘evolutionary palimpsests’ that are ‘readout[s] from the animal and its genes, [a] richly coded description of ancestral environments’ (Dawkins, p. 2).

On a page on which there appears a photograph of a camouflaged lizard in a stony terrain, Dawkins writes:

This horned lizard of the Mojave, whose skin is tinted and patterned to resemble stand and small stones, embodies a prediction, by its genes, that it would find itself born (well, hatched) into a desert. Equivalently, a zoologist presented with the lizard could read its skin as a vivid description of the sand and stones of the desert environment in which its ancestors lived. And now here’s my central message. Much more than skin deep, the whole body through and through, its very warp and woof, every organ, every cell and biochemical process, every smidgen of any animal, including its genome, can be read as describing ancestral worlds. In the lizard’s case it will no doubt spin the same desert yarn as the skin. ‘Desert’ will be written into every reach of the animal, plus a whole lot more information about its ancestral past, information far exceeding what is available to present-day science.

—Dawkins, p. 4.

And, while I have no evidence that any of the foregoing would have been playing on Laura Marling’s mind when she wrote the material on Patterns in Repeat, it’s all related in my mind given that she does seem to be getting at what recurs through generations and what’s knowable and not-yet-knowable in the cosmic dance.

Just patterns in repeat like they’ve always been, and forevermore.

This was such a joy to read, thank you. When I was an academic I often looked for patterns in things as a way of making sense of them and I so enjoyed reading this in connection to other viewpoints and disciplines.

What a fascinating piece! Very much enjoyed reading it.