'The Simple Majesty of Foliage': Leaves, Songs and Metaphors

A 'Songs for Every Season' post.

Prompted by a couple of recently released songs—Willie Nelson’s ‘Last Leaf’ and Nev Clay’s ‘Green Leaves’—and by the arrival of autumn in the North East of England, I’ve been thinking about songs that use leaves as metaphors for time, age, experience and mortality. I’ve also been thinking about autumnal vibes more generally, in song lyrics, sounds, record covers, music videos and other places.

Songs are fragments are words are leaves are objects that come and go. They generate and fade away and disperse. With the leaves starting to scatter where I live, I’m laying down these lines as fragments rather than as trunks, branches and stems. I’ll stay as tidy as I can, but I won’t sweep everything up. Some words, like leaves, have to lie where they fall.

‘Last Leaf’ is a song written by Tom Waits and Kathleen Brennan. It appeared on Waits’ 2011 album Bad as Me. Its lyrics speak of a stubborn persistence in the face of autumn and winter, of hanging on after the rest have fluttered to the ground. Then it makes a claim to a species-defying continuity by connecting leaves to songs:

I fight off the snow I fight off the hail Nothing makes me go I'm like some vestigial tail I'll be here through eternity If you want to know how long If they cut down this tree I'll show up in a song

What an idea. The more I’ve thought about songs while working on my Songs and Objects project, the more I’ve been drawn to the idea of songs as viral in ways that go beyond short-term popularity and reach. I think songs are much more like long-haul viruses that move from host to host, jumping passengers as a way to stay fuelled and on the move. To stay alive.

Waits and Brennan go further. They take an object from nature’s own renewal programme, the humble leaf, and grant it the power not only to regenerate, but also to transmute. They do this through a brilliant lyrical nod to evolutionary biology—how many other songs are there that use ‘vestigial’, let alone ‘vestigial tail’?

Waits was 61 when he recorded ‘Last Leaf’. Joan Baez was 77 when her cover version appeared on the 2018 album Whistle Down the Wind. Willie Nelson is 91 as his version appears, first as a single and soon as the title track of a new album of covers. Age, then, is bound to be a factor in responses to the song. The lyric encourages that, and the layers of experience associated with these three veteran performers only enrich those sentiments.

Like the track ‘Die When I’m High’—a duet between Willie Nelson and his son Micah that I referred to briefly in a recent piece on Willie as an ageing icon—’Last Leaf’ comes with a video featuring Micah’s timelapse animation of his father’s face.

Micah’s animation further emphasises the song as the reflection of a long-lived artist whose work has, for decades, centred on time, age and experience. Willie, after all, was singing ‘The Healing Hands of Time’ and ‘Funny How Time Slips Away’ back in the 1960s. The following decade brought concept albums such as Yesterday’s Wine (1971) and Phases and Stages (1974) and songs like ‘December Day’, with its lines about ‘the green leaves of knowledge … waiting to fall with the Fall’.

‘Green Leaves’ is a song by Newcastle-based singer-songwriter Nev Clay. Something of an institution in my neighbourhood (and beyond), Nev has, in the words of his Bandcamp bio, ‘been clarting around the local music scene for 30 years’. The version of the song that I described earlier as recently released is the one that features on Nev’s wonderful recent album So Little Happened for So Long.

An earlier recording of ‘Green Leaves’ was released via Bandcamp as part of a 2020 EP, in a version that sounded closer to what I’d seen Nev play live (guitar and vocal rather than the banjo of the newer version).

I emailed Nev to thank him for his album and the lovely note he’d put in the LP I purchased through Bandcamp. I mentioned that I hoped to write about ‘Last Leaf’ and ‘Green Leaves’ in an upcoming piece (this one) that would be, in part, about metaphors in songs.

Nev was kind enough to respond and to share some interesting observations about songwriting. What he said made me realise I shouldn’t always be so quick to apply metaphorical thinking to song lyrics:

I have to say that, though I love a well-turned metaphor in literature or poetry … I tend to avoid them like the, er, plague (to use an overworn metaphor). Ever since I wrote Green Leaves, I've been mindful of the risk of it being read metaphorically, and at various gigs I've tried to disabuse audience members of that impression... but it's unavoidable, isn't it. And, of course, I lean into it, with the torn up saplings in the second verse.

And:

Long ago, I attended some writing classes run by Billy Liar, a short-lived North-East creative project, upstairs at what was the Printer's Pie, and their advice to "write like you're a CCTV camera" seems to have stuck. Perhaps it's just an over-active cliche-detector on my part. In that wonderful Willie Nelson song, of course, there's no cliche about it, it's the perfect image, fresh and unique, and completely congruent with all we know about him... just beautiful. Love the "vestigial tail" line too!

As for my song, I was walking from my flat in Longbenton to the local off-licence in Summer 2020, via a little cut that leads to the main road. There's two ash trees there, and this particular day, I noticed that their leaves had already started falling, though it was early in the season. I was struck by the bright green of the leaves, already abandoned though still rich with chlorophyll (the photo on Bandcamp that accompanies the 2020 EP doesn't really do them justice, but those were the leaves). And by the time I got home, the line had formed. It's as prosaic as that. I suppose that's how it works sometimes - you see something in the world and, in reverie (in my case, a daily meditation on impermanence), that triggers a chain of associations. "Like a bird on the wire..."

Nev’s reflections made me remember a response I’d had to my presentation about Willie Nelson’s hands. After I’d talked about how Nelson’s guitar, Trigger, gets used as a stand-in for its owner, a colleague mentioned that metaphor must be important for my project. I agreed, but I pointed out that, while I am often talking about metaphors, objects are not always metaphors, and processes don’t only require objects for metaphorical purposes. When I use a kettle to make a cup of tea, the kettle is not a metaphor. It’s the object required to complete that process. A metaphorical kettle is no use to me when I need a cup of tea.

Sometimes the green leaves fall before the gold. And sometimes a leaf is just a leaf.

‘Autumn Leaves’—arguably the most famous song of the season, and one that, at the time of writing, has 1794 versions listed at Secondhand Songs—began life as ‘Les Feuilles Mortes’. In the French song, with lyrics by Jacques Prévert for Joseph Kosma’s music, there’s a connection between leaves and songs:

Dead leaves are collected with a shovel Memories and regrets too And the north wind carries them away In the cold night of oblivion You see, I haven't forgotten The song you sang to me

Here’s Juliette Greco wringing the pathos from it:

Johnny Mercer’s English lyrics don’t retain the leaf/song comparison. Mercer goes for a fuzzy nostalgia in place of Prévert’s chilly wind, creating a song that fits a by-then familiar romantic template. It’s the ideal song for a ‘seasoned’ performer like Frank Sinatra, for whom, in 1957, it acts as a kind of precursor to the more drawn-out metaphors of his 1965 album September of My Years.

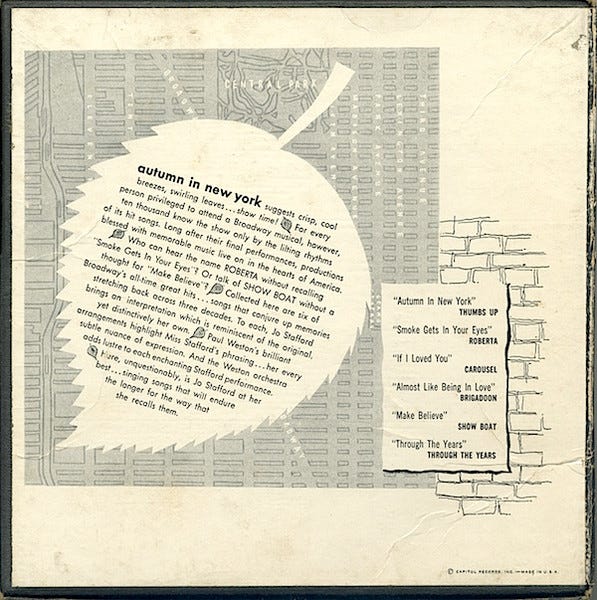

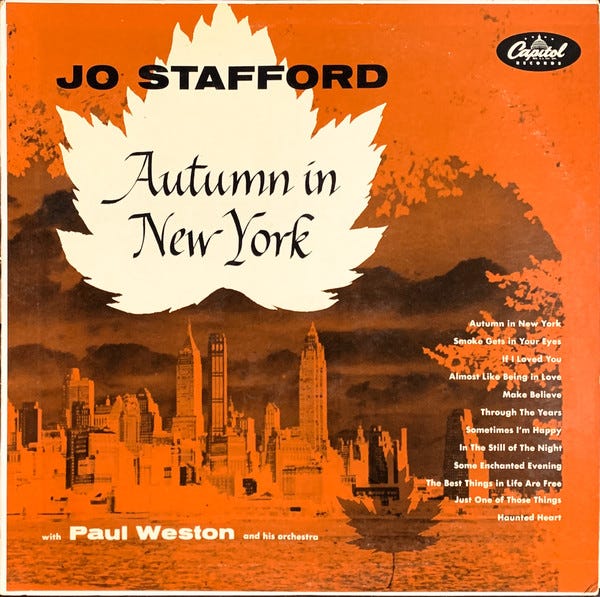

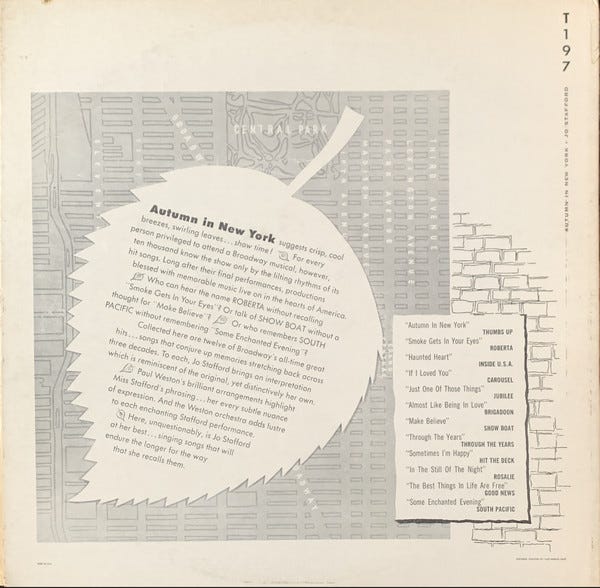

Jo Stafford was the artist that Mercer selected to release the first version of his song. It appeared in 1950 on a disc backed with Stafford’s rendition of Vernon Duke’s ‘Autumn in New York’, a song from the 1934 musical Thumbs Up! ‘Autumn in New York’ became the title track of an album Stafford released with Paul Weston arrangements, an album worth noting as much as anything for the leaf-based sleeve designs that graced the 1950 original and the extended 1955 reissue.

If we were to stop and consider all the classic album covers that have used leaves since then, we’d be here until summer. I invite you to listen, instead, to Jo Stafford’s ‘Autumn Leaves’, which wasn’t on the Broadway-themed Autumn in New York because it wasn’t a Broadway tune.

Before it was a Substack, Songs and Objects began life as a podcast. I had to give it up because of other commitments, but it survived long enough to need a logo. Looking through my archive of photos in search of objects that might relate to songs, I found a picture of a leaf.

Because many people don’t like it when you compare music to objects, I often write about what I see as arbitrary distinctions between things and processes. I shouldn’t rise to the bait, but I can’t help it. Perhaps it’s because I think they’re right and I’m mistaken, that I’m on a dead end with my songs-and-objects thing. But the basic ideas have been with me for a long time and show no signs of fading away. I chose a leaf as the logo for my short-lived podcast because it reminded me that objects are always in process and that processes rely on objects.

Leaves are pages in books, which are also used as metaphors for time, age and experience. Turning over a new leaf. A blank page.

Whitman’s Leaves of Grass: the poet’s life experience becomes a paean to the collective.

Francis Ponge’s poems about things: pebbles, ferns, trees that cancel themselves.

Tired of having restrained themselves all winter, the trees suddenly take themselves for fools. They can stand it no longer: they let loose their words—a flood, a vomiting of green. They try to bring off a complete leafing of words. Oh well, too bad! It'll arrange itself any old way! In fact, it does arrange itself! No freedom whatever in leafing . . . They fling out all kinds of words, or so they think; fling out stems to hold still more words. “Our trunks,” they say, “are there to shoulder it all.” They try to hide, to get lost among each other. They think they can say everything, blanket the world with assorted words: but all they are saying is “trees.” They can't even hold on to the birds who fly off again, and here they are rejoicing in having produced such strange flowers! Always the same leaf, always the same way of unfolding, the same limits; leaves always symmetrical to each other, symmetrically hung! Try another leaf—The same! Once more—Still the same! In short, nothing can put an end to it, except this sudden realization: “There is no way out of trees by means of trees.” One more fatigue, one more change of mood. “Let it all yellow and fall. Let there be silence, bareness, AUTUMN.”

—Francis Ponge, ‘The Cycle of the Seasons’, translated by Beth Archer in Francis Ponge, The Voice of Things.

The pebble, final offspring of a race of giants, is of the same stone as its enormous forebears. And if life offers no faith, no truth, it nonetheless offers possibilities. For trees there may be no way out of their treehood “by the means of trees”—leaves wither and fall—but they do not give up, they go on leafing season after season. They are not resigned. This is the first “lesson,” the heroic vision, and the first weapon against mortality. The second is the creative urge, the “will to formation” and the perfection of whatever means are unique to the individual: the tree has leaves, the snail its silver wake, man his words. He also possesses all the “virtues” of the world he lives in: the fearful fearlessness of the shrimp, the stubbornness of the oyster, the determination of water, the cigarette's ability to create its own environment and its own destruction. The ultimate weapon is the work of art, the sublime regenerative possibility, which man carries within himself like the oyster its pearl, the orange its pip. These are not “morals” in any strict didactic sense, but they are lessons, of the kind that the Renaissance learned from antiquity—models of exemplary virtue to follow.

—Beth Archer, Introduction to Francis Ponge, The Voice of Things.

Leaves are things consumed by humans and nonhumans. Not just lettuce and kale, but greenery that is dried, boiled, soaked and smoked.

A hopeless task to list the many hymns to weed, but worth noting the excellent line in a song written by Lukas Nelson for his father in which Willie reflects on time by singing that ‘the weed is getting stronger’.

For a long time, I’ve cherished Grace Jones’ 1978 recording of ‘Autumn Leaves’. I enjoy its retention of the French lyrics, its smooth glide from jazzy standard to wafty disco, its bass groove, and Grace’s vocal flight.

How best to compare the smell of woods in autumn to those in spring? Mellowness, muskiness. Woody rather than sappy. A different cool dampness that enters the nostrils along with the scent. A different productivity: fulsomeness on the ground rather than on the branches, but life also blossoming brownly around trunks and bark. The onset of mushroom season.

I adore Dalva de Oliveira’s recording of Ary Barroso’s ‘Folha Morta’ (‘Dead Leaf’), a 1953 single that’s closer to ‘Les Feuilles Mortes’ than ‘Autumn Leaves’ in its air of unhappiness.

I've had love I had affection I've had dreams The unpleasantness took my soul Along sad paths Today I am a dead leaf That the current carries Oh, God! How unhappy I am!

There’s something about that beat that belies the misery. Maria Bethânia’s beautiful version from 1971 brings the sadness, though again I’d say the music injects a kind of heart-weary warmth. Gal Costa, in 1980, does glorious things with Barroso’s phonemes, alternating between curiosity, disbelief and resilience.

Different shades of saudade.

Nat King Cole singing ‘Autumn Leaves’ in Japanese.

Leaves as fragments of a larger whole: what might that mean for thinking about songs and cells and writing?

Another leafy classic from Brazil:

When I step on dry leaves Fallen from a mango tree I think about my school And the poets of my first season I don't know how many times I climbed the hill singing ...

Like many fallen leaf songs, Nelson Cavaquinho’s ‘Folhas Secas’ (‘Dry Leaves') looks back to younger days and hotter seasons. The line about climbing the hill is followed by another that mentions the burning sun. The word ‘estação’, which I’ve translated as ‘season’, could also be ‘station’. As Portuguese and other languages remind us English speakers, seasons are stations of the year, stages we pass through.

But there’s some neater wordplay than that happening in this song. By bringing the words ‘mangueira’ (mango tree), ‘escola’ (school), ‘primeira’ (first/primary) and ‘estação’ together in his first verse, Cavaquinho is recalling for himself and for his listeners the historically important Rio samba school with which he was affiliated, the Estação Primeira de Mangueira. The song becomes a reminiscence of climbing the hot hills of the Mangueira neighbourhood to take part in samba sessions. The leaves that drop from its heights drift through time and space, just like those endlessly renewable sambas.

This gorgeous version is sung by Elis Regina.

Bob Dylan included ‘Autumn Leaves’ on Shadows in the Night, one of his Sinatra-inspired albums of standards. As he told Robert Love for an AARP feature, the song demands experience and conviction on the part of the singer:

You have to believe what the words are saying and the words are as important as the melody. Unless you believe the song and have lived it, there’s little sense in performing it. “Some Enchanted Evening” — that would be one. Another one would be “Autumn Leaves.” That’s a song that’s been done to death. I mean, who hasn’t done that song? You sing “Autumn Leaves” and you have to know something about love and loss and feel it just as much, or there’s no point in doing it. It’s too deep a song. A schoolboy could never do it convincingly.

I couldn't think of any Dylan songs that extensively delve into the topic of leaves falling. That reminded me that Dylan deals in fragments more than extended metaphors, especially in his later work. I like the following autumnal leaf reference, though, as it speaks of the approaching end of an epic journey and the potential start of a new one:

Mona Baby, are you still in my mind - I truly believe that you are Couldn’t be anybody else but you who’s come with me this far The killing frost is on the ground and the autumn leaves are gone I lit the torch and I looked to the east and I crossed the Rubicon

Leaves as collective and individual, as saying something about community. When leaves fall from the trees, there is still community: scattered, migratory, diasporic. The impression I have of fallen leaves on the ground is of a reordered collective.

In his essay ‘On Transience’, Sigmund Freud recounts a walk in the countryside ‘in the company of a taciturn friend and of a young but already famous poet’. The poet is dejected because of his awareness of the transient beauty of the nature surrounding them:

The proneness to decay of all that is beautiful and perfect can, as we know, give rise to two different impulses in the mind. The one leads to the aching despondency felt by the young poet, while the other leads to rebellion against the fact asserted. No! It is impossible that all this loveliness of Nature and Art, of the world of our sensations and of the world outside, will really fade away into nothing. It would be too senseless and too presumptuous to believe it. Somehow or other this loveliness must be able to persist and to escape all the powers of destruction.

Freud tries to convince his pessimistic companions that there is gain rather than loss in such things precisely because of their transience: ‘Transience value is scarcity value in time. Limitation in the possibility of an enjoyment raises the value of enjoyment.’ He asserts that nature, unlike human life, is eternal even though the seasons wreak temporary changes. As his companions fail to see his version of events, Freud surmises that they were experiencing ‘a foretaste of mourning’, the pain of which has ‘interfered’ with ‘their enjoyment of beauty’.

I’ve been in landscapes where the changing colours of leaves on trees en masse left me breathless. I think of autumn in southern Chile, six months separated from England’s, of the almost incomprehensible beauty glimpsed through the car window on a road between Puerto Montt and Valdivia.

I can reach some beautiful colour-soaked woods and forests without travelling too far from my home. Last November, passing through the Northumberland village of Blanchland, I had to stop the car so that I could walk back up the avenue of golden trees we had just passed through.

But, given that I spend much of my time in urban and semi-urban areas, it’s often smaller, subtler signs of autumn that grab me. On a run the other day, I passed spears of hedgerow plants offering shades of green, yellow and red: thin brilliant palettes. I don’t have photos of them, but they’ve made their impression.

Jo Stafford braving the elements of a BBC studio in 1961.

How refreshing to run on an autumn morning like today’s: the cool, slightly damp air, the leaves on the ground, the changing hues of the hedgerows and trees, the brightness of red berries.

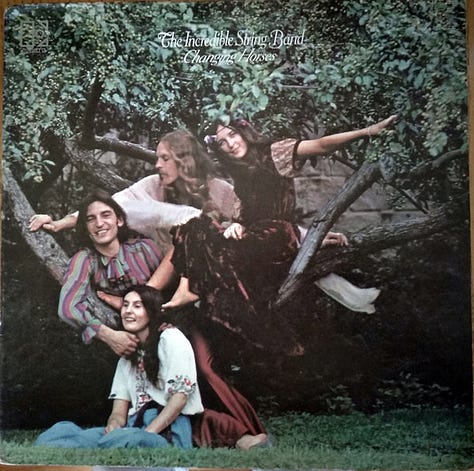

While running, I thought about leaves and cells, about the Incredible String Band’s ‘A Very Cellular Song’, about how photos of the ISB often showed them posing in nature. Then my mind skipped to the cover of Jethro Tull’s Songs from the Wood and to Midlake videos.

While there’s something very woody about The Courage of Others, not least the leafy video for ‘Rulers, Ruling All Things’, it’s an album about seasons rather than autumn per se. There are more songs about the end of winter and the arrival of spring than there are about decay. So, too, with the Incredible String Band, whose cellular song celebrates renewal over everything.

Is it because we’re so bogged down in the local that we feel the manifestation of changing seasons so strongly? After all, it’s not as though most of us can be in many parts of the world within a short space of time, if at all. We may know that autumn here means spring on the other side of the world, but it’s a different thing to experience that simultaneity.

Perhaps that’s why the ISB sought escape from the local in lyrics, sounds and happenings that looked elsewhere.

Should we be glad that the song has no end?

A week ago, following advice from the wonderful Carol Klein, I carefully cut up the leaf of a begonia ‘Lucerna’ that had fallen from the plant in an attempt at propagation. I’ll have to wait a while to see if I’ve been successful, but knowing that Carol has so much success with this method only puts me further in awe of leaves.

The grass still trembled, the old chestnut tree murmured with the mouths of an entire grove, red Autumn let fall a leaf, steadfast the hours on earth their task pursued. Because you are only a seed, the chestnut tree, the autumn, earth, water, sky, silence prepared the germ, the floury density, the maternal eyelids which, buried, will open up anew towards heaven the simple majesty of foliage, the damp, dark network of new roots, the dimensions old and new of another chestnut tree on earth.

—Pablo Neruda, ‘Ode to a Chestnut on the Ground’, translated by Carlos Lozano, The Elementary Odes of Pablo Neruda

It’s just over a year since the felling of the tree at Sycamore Gap.

From Wikipedia:

The Sycamore Gap tree or Robin Hood tree was a sycamore tree next to Hadrian's Wall near Crag Lough in Northumberland, England. Standing in a dramatic dip in the landscape created by glacial meltwater, it was one of the country's most photographed trees and an emblem for the North East of England. It derived its alternative name from featuring in a prominent scene in the 1991 film Robin Hood: Prince of Thieves. The tree won the 2016 England Tree of the Year award.

The tree was felled in the early morning of 28 September 2023 in what Northumbria Police described as "an act of vandalism". The felling of the tree led to an outpouring of anger and sadness. Two men from Cumbria, aged 38 and 31, were arrested in October 2023 and charged in April 2024 with criminal damage both to the tree and to the adjacent Hadrian's Wall.

Sycamore Gap is about 37 miles west of where I live. I took these pictures of what remains of the tree on a visit to Hadrian’s Wall in May of this year.

The tree lives on as a photographic reference, as a memory, as part of a new exhibition recounting its life, as saplings grown from its seeds, and, as the sign in my photo wished, as a still-alive stump that ‘might sprout new growth’.

‘If they cut down this tree, I'll show up in a song.’

While I was working on these fragments, news broke that Kris Kristofferson had died. Like others, I turned to the many classic songs that he wrote as I processed the news. I also thought about his role as one of the Highwaymen, with Johnny Cash, Waylon Jennings and Willie Nelson, and about the Jimmy Webb song that gave the band their signature tune. It’s a song about renewal and regeneration, about transmutation, an eras-spanning tale of the highwayman-sailor-dam builder-astronaut who may return to Earth as a drop of rain.

Having a different singer take each verse, assume each character, was a brilliant decision, one that turned the prior neglect of Webb’s song into what the songwriter saw as a process of ‘predestination’. Each singer ‘dies’ at the end of each verse but promises to return; each returns to sing the collective lines about coming around and around. And each verse offers a variant of the one that comes before or after, a reminder of the cyclical nature of song, of verses and refrains and versions and recordings and performances and all the things that keep song objects alive. Webb seems to hint at that intra-song cycle when, in the version of ‘Highwayman’ that he recorded for his Ten Easy Pieces album, he adds ‘oh, and here we go’ before the final verse and again at the close of the song. It’s something you might sing or say before adding one more refrain during a singalong. It could also simply be announcing a departure.

Kristofferson’s death also means, of course, that Willie Nelson is now the only remaining member of the Highwaymen, the last leaf of that tree.

Willie Nelson performed ‘Last Leaf’ at Farm Aid on 21 September with his sons, Lukas and Micah. It was beautiful.

Another wonderful deep dive. Through coincidence/record rotation I was just listening to Jo Stafford again a few days ago, and that video from the Judy Garland show was simply astounding.

Although he is sometimes mocked for it, Van Morrison has shown an obsession with actual falling/fallen leaves in many of his songs, again as "elements of the painting" rather than as metaphors in any particular way. As early as "Cypress Avenue" his narrator recalls being entranced as "the leaves fall one by one by one, and call the autumn time a fool." Then in the Moondance title song, "all the leaves on the trees are falling, to the sound of the breezes that blow."

Three years later, he recast his song "Purple Heather" (which he claimed he "wrote," but it is largely a remake of Wild Mountain Thyme -- a summer tune) as an autumn reverie, observing that "when the summertime is gone, and the leaves are gently turning" he will go with his love into the mountains. On the same record, his trance-inducing "Autumn Song" begins with "leaves of brown, they fall to the ground...and it's here, over there, leaves abound" -- for a narrative all about the seasonal changes and celebrations brought by autumn.

A decade later he cast the changing color of leaves in a starring role in the title song of "Sense of Wonder," actually naming as many leaf changing colors as the narrator could come up with in one verse, while also offering with resignation this thought about the emotional state of observing leaves change: "It's easy to describe the leaves in the autumn, and it's oh so easy in the spring....but down through January and February, that's a very different thing." A schoolboy song of nostalgia like "Orangefield" begins with "On a golden autumn day, you came my way...in Orangefield." (And while I suppose the narrator could have been referring to the odd sunny autumn day in Belfast, I've always understood that golden day to be attributed to the fall color change).

There are other examples of his leaf obsession, but I've stretched any reader's patience already.

Finally, an iconic song by the great Australian songwriter Paul Kelly, "Leaps and Bounds," captures perfectly the month of May -- autumn in antipodean nations -- with a non-visual reference to leaves, in this case their incineration -- "I'm breathing today, the month of May, all the burning leaves." For Australians, that early line in the song firmly cemented a personal experience of leaves in all listeners.

Thanks for all of your writiing Richard.

This is a lovely piece, Richard. I live in a beautiful, damp part of the US where we are surrounded by trees. Western Oregon is essentially a temperate rainforest. The autumnal colors in our neighborhood, on our road, and the western hills that outline downtown Portland to the west - are stunning. It also means, however, that I am raking leaves for literally two+ months. But it is so worth it because not only do the trees bring our house lovely shade in the summer, but they are home to many vocal crows, other birds and families of raccoons and squirrels.

While reading this, I also couldn't help but think about Nick Drake's album title, 'Five Leaves Left,' but also a couple of quotes the American artist, Georgia O'Keefe, once said about her flower paintings:

"Nobody sees a flower really; it is so small. We haven’t time, and to see...takes time. It’s like having a friend. Having a friend takes time."

And...

"I decided that if I painted a flower huge, you cannot ignore its beauty.”.

Both of these quotes are so powerful, as art is about learning how to see and music is about listening. Within the songs you listed, you clearly took the time to become close friends with them, and as with O'Keefe's large flower paintings, you clearly can't ignore the song's beauty.

One of the things I vividly remember about my time during the pandemic is that my wife and I would go on very long walks throughout the city, and we noticed the little things that many of us miss amongst the busyness of our normal lives. Taking the time to see the kaleidoscopic colors of spring, the cluster of bees on flowers in the front gardens throughout Portland's neighborhoods, the sounds of kids playing, and eventually the first sign of autumn on the trees were all key moments during the 2020 lockdown. It also brought a sense of calm and beauty, as for over 100 days the evenings descended into chaos with the riots and tear-gassed skies in the night (which lasted over three months in Portland).

Lastly, Nelson is right—the weed is stronger. I stopped smoking because it's too strong. But it's also not weed growing in the wild. The stuff grown today is genetically modified, or cross-pollinated to blow your head off. It's also legal in Oregon, and the smell of weed is part of the urban fabric and tapestry of this city.

Thank you again for sharing your thoughts on leaves, songs, and the artists behind the lyrics.

PS: Oh, I just remembered... Last year, we cut a small bit off a houseplant and put it in a glass of water until it grew roots. We then planted it in its own pot, and it is now a healthy plant. 😊