In the first week of July—on the fourth, as chance would have it—I’m scheduled to give a presentation at a gerontology conference. It’s a slightly unusual gig for me—I generally present at music, media or cultural studies events—but the panel I’m on reflects a longstanding interest in how popular music responds to and represents time, age and experience. This was the theme of my book The Late Voice, though I’ll be presenting on a musician—Willie Nelson—who was only briefly mentioned in that book.

Well over a decade ago, when I was first working on The Late Voice, I planned to include a chapter on country music in which I’d explore the work of Nelson, Merle Haggard, Johnny Cash, Kris Kristofferson, Guy Clark and others. But, as anyone who regularly reads this newsletter will be aware, I struggle with brevity and it soon became clear that it would be a book of five long chapters rather than eight to ten shorter ones. The country chapter didn’t make the final cut, but I hung on to my notes and to some of my thoughts from that time.

A photograph

While keeping a set of notes on Willie Nelson for the planned country chapter of The Late Voice, I was struck by a photo posted online that showed Willie Nelson’s hands and his battered guitar, Trigger. It was posted to the Facebook page of Billy Bob’s Picnic on 8 May 2013 with the caption ‘Trigger!—with Willie Nelson’. Nelson was tagged, which is why I saw the photo. No credit was given for the photographer, nor have I found one since, despite trying several image searches. (If any readers know who took this photo, I’d love to find out.)

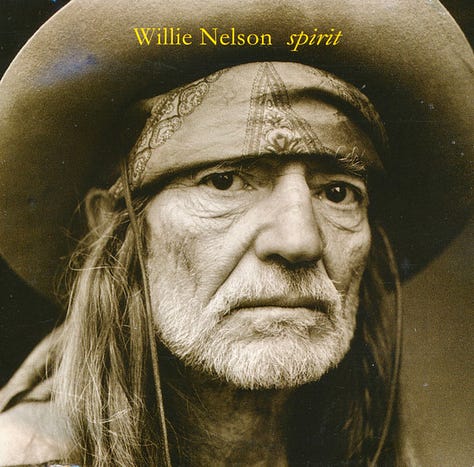

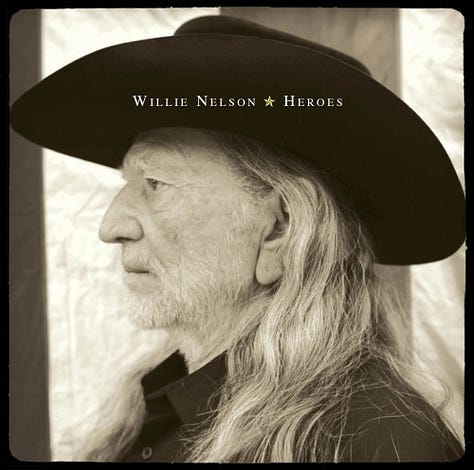

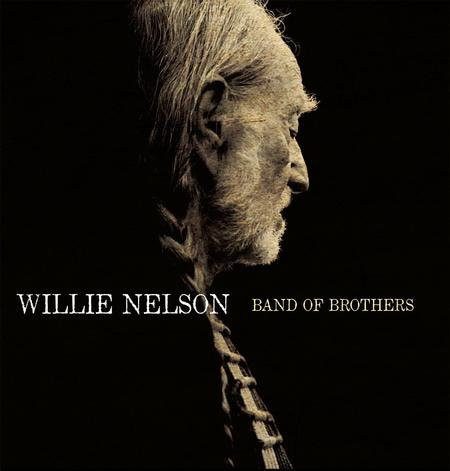

By then, I’d already been planning to include a section in my planned chapter on how photography—and, increasingly, black and white or sepia photos—had become a recurring feature in promotional material for Nelson and other veteran country artists, and how those photos sent out messages about biography, time, age and experience. This picture encapsulated that idea.

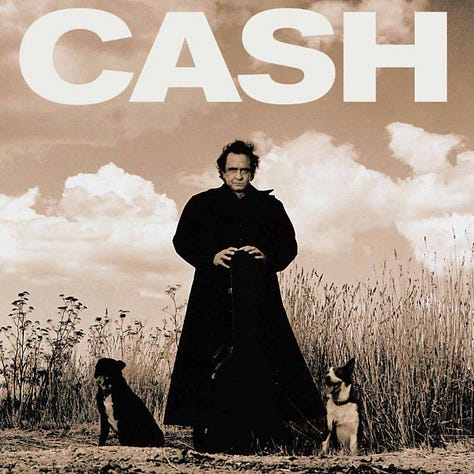

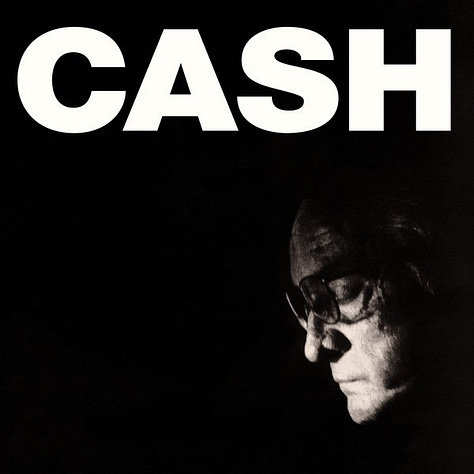

We have seen this happen elsewhere in country music iconography. The starkness of the imagery accompanying Johnny Cash’s American Recordings was as vital as the albums’ sound world in establishing a sense of Late Cash.

William Ferris, in the introduction to Jim McGuire’s Nashville Portraits, writes, ‘Portraits of musicians … become an extension of the artists’ musical performances, a part of their personas. The craggy face of Johnny Cash … is now as familiar a part of our photographic history as it is of our musical history.’

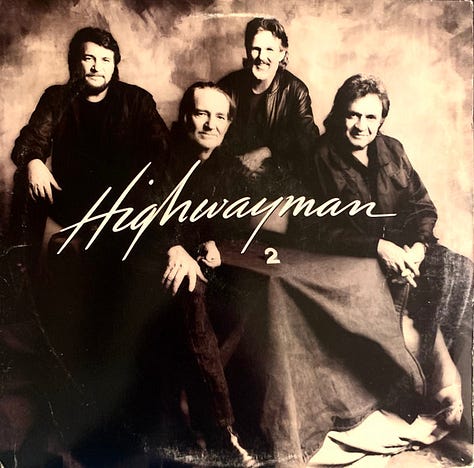

And so it is for Willie Nelson. As with Cash’s late albums, there has been a tendency with Nelson’s to emphasise his age through the use of black and white photography. This seems to have evolved from a brief period in the late 1980s and 1990s where softer focus sepia imagery was often used to evoke drama. Sometimes, as with Nelson’s Across the Borderline and Highwayman 2, I feel the soft-focus sepia has been used to simultaneously evoke history while lessening the impact of the artists’ ageing bodies. By the time of Cash’s first volume of American Recordings in 1994, the images become starker and more finely detailed, even when sepia is still being used. A similar process happens with Nelson’s albums. This feels to me more like a celebration than a masking of the ageing musician.

By the time the photo of Nelson’s hands and guitar was posted to Facebook in 2013, there had been a definite shift to stark, finely grained black and white, a move clearly designed to evoke responses around age and experience. One Facebook commenter on the hands photo employs the brevity typical of the platform, writing ‘Look at the HIDE on him !!!!!!!!!!!’. Another uses the single word ‘SEASONED…’.

Words like ‘craggy’, ‘hide’ and ‘seasoned’ can be read with positive or negative implications. My reading of them in the context of ageing country music personas is that they are meant positively, that these commenters are seeing value in these features as representations of an authenticity born from experience. This is clearer in some of the longer responses on the Facebook photo: ‘Wow, imagine those are the hands that held a pen to write “The Night Life”, “Crazy”, “Hello Walls”, etc., songs that have become part of the landscape’; ‘I would love to hear all the songs and places those hands have seen and played’. These last two highlight the way that fans of musicians project themselves and their experiences onto their representative artists. ‘We all get older but we still feel the same’, says one; another—sightly dismissive perhaps of other commenters—writes, ‘They are just 80 yr old hands ..no big deal ..talented hands’.

Some of the comments use metaphors drawn from Nelson’s songs. One reads ‘HANDS OF TIME’, evoking Nelson’s song ‘Healing Hands of Time’ So does another: ‘could say these are the healing hands of time always feel better after listening to willie’.1 Another—‘Aging with time like yesterdays wine . ...better and better’—refers to Nelson’s ‘Yesterday’s Wine’, one of his many songs about time, experience and ageing. The lyric ‘Now you wear your skin like iron…’, which another commenter uses, comes from a song written by Townes Van Zandt that Nelson covered in a popular duet with Merle Haggard in 1983.

This category of comments overlaps with another that focuses on texture and materiality, connecting Nelson’s hands to the weathered body of his famous guitar, Trigger: ‘reminds me of an ageless oak tree - the troubadour of another time’; ‘His hands r weathered just like the guitar’; ‘I think that old guitar & the hands have become one. Priceless!!’. Which brings me to the next point I want to make about the depiction of Willie Nelson as an ageing musician whose work evokes time and experience.

Trigger as biographical object

Willie Nelson is one of a small number of musicians who work with an instrument revered enough to have a name known by thousands. Trigger is the adapted Martin N-20 nylon-string classical acoustic guitar that Nelson has been using since 1969. The guitar—famous enough to have its own Wikipedia page as well as documentaries and magazine features—is named after Roy Rogers’ horse, leading to lines such as the following from Michael Hall’s 2012 Texas Monthly feature on the instrument: ‘Willie treats Trigger like a horse, and he rides him hard’.

The metaphor of the weapon seems just as apt, via the triggering of the solo, run or intro. There’s also the violence of the strum, as evidenced in the gaping hole caused by playing a classical instrument as though it were an instrument with a guard. Nelson’s longtime harmonica player Mickey Raphael, one of the commentators in the 2015 Rolling Stone documentary about Trigger, mentions bits of wood flying off the guitar during a performance of ‘Whiskey River’ like ‘shrapnel’.

Thinking about Trigger, I’m reminded of the work of the anthropologist Janet Hoskins, especially her 1998 book Biographical Objects: How Things Tell the Stories of People’s Lives. In her study of a betel bag owned by one of her informants, Hoskins explains that the bag is something that carries stories, acting as both a prop to storytelling, as the container for the ritual objects necessary for storytelling, and as a receptacle for her informant Maru Daku’s other way of recording stories: his notebook.

While there is always a risk of undoing the cultural specificity of anthropological work by making broader comparisons, the idea of memory containers is widespread, as is the practice of going through the contents of containers to (re)create lives and narratives. As Hoskins observes, overlaps can be found between her work and that of sociologists such as Daniel Miller, who studies the (often mass-produced) objects that people keep in their homes, the values that get attached to stuff, and the ‘comfort of things’. Biographical objects can also be compared with the ‘evocative objects’ described by Sherry Turkle.

From a life-writing perspective, it’s interesting to note the mutual ageing of Willie Nelson and Trigger, a process that Nelson himself makes explicit in interviews. Trigger as a biographical object can be thought of as a container or holder of other objects, each metaphorically connected to other stories and to an overarching cohesive story. Actually, Nelson and Trigger are both containers: of songs and sounds and stories. Both need to be activated to bring these things to life, and both activate each other. ‘Without Willie, there would be no Trigger’, writes Hall in his Texas Monthly piece, ‘And it’s only a slight exaggeration to say that without Trigger, there would be no Willie. Willie likes to say that his guitar will probably wear out just about the same time he does’.

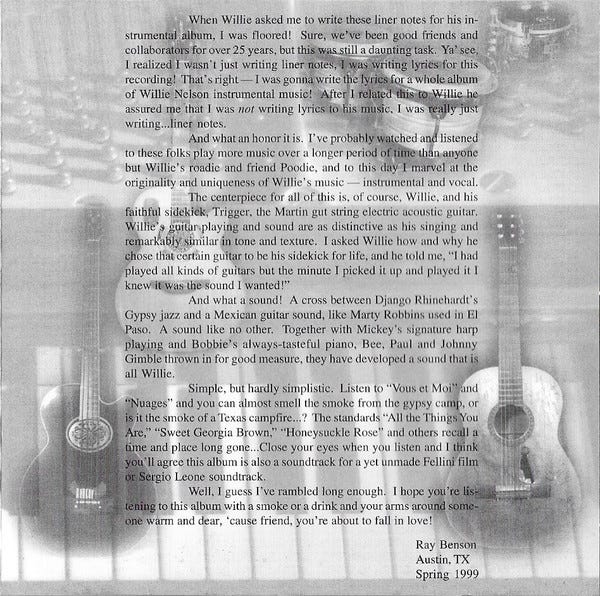

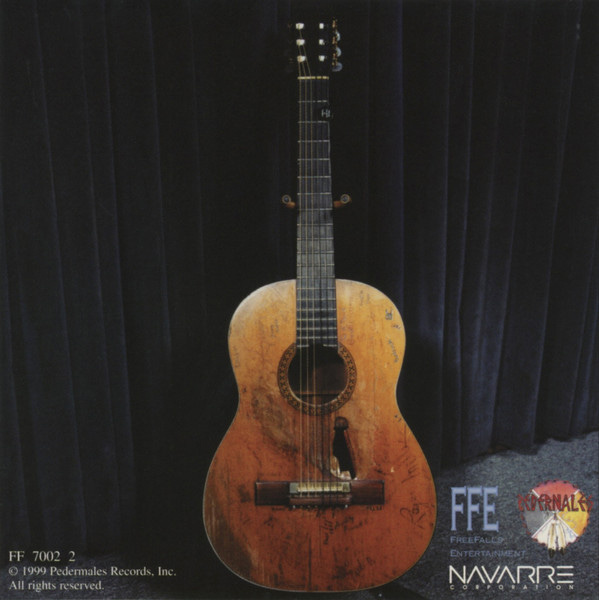

It seems to me that Trigger has come to have an ever-larger role in the story of Nelson’s career and how Nelson’s music is marketed through visual media such as album covers. While I haven’t done extensive research though Nelson’s vast discography, initial searches through Discogs and my own collection suggest 1999’s Night and Day as a possible start of a Trigger trajectory that has continued unabated ever since.

Prior to this, there had been what I’d previously picked up on—the increasing use of sepia and black & white photography—but on albums like Across the Borderline (1993), Just One Love (1995) and Teatro (1998), the focus had remained on Nelson’s head, whether adorned by a hat or focussing on his signature braids and beard. Night and Day is an instrumental album, arguably forcing more attention on the guitar. Ray Benson’s liner notes mention Trigger by name and discuss Nelson’s guitar style. The text is superimposed on an image of Trigger and other instruments, while Trigger features solo in a photograph on the back of the CD liner.

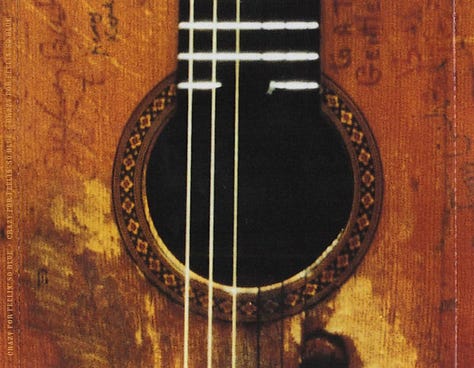

A year later and Trigger has been promoted, becoming a stand-in for Nelson on the front cover of Milk Cow Blues. The guitar also has a prominent role in the CD packaging, including a centrespread in the booklet and a close-up in the disc tray.

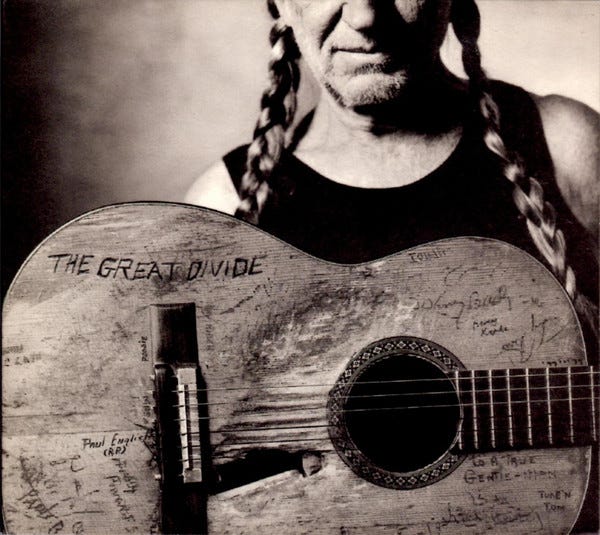

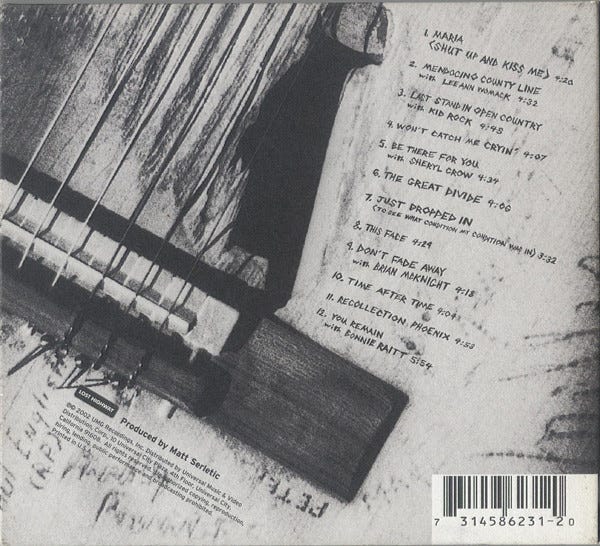

2001’s The Great Divide continues the Trigger-happy trend, with a photo that cuts part of Nelson’s face off so that the guitar is centred. Here, the album title appears as if it has been scratched into the surface of the wood, echoing the famous signatures that Trigger has collected over the years; on the rear, the song titles appear the same way, as though these songs have been birthed from or imprinted into the instrument, as though it’s Trigger who brings them to life and marks their memory. The 2023 vinyl reissue of The Great Divide follows a similar pattern but brings the names of Nelson’s human collaborators to the front cover.

What popular musicians can tell us about ageing

Well, I’m nearly 2000 words into what that photograph of Willie Nelson’s hands playing Trigger gets me thinking about. I’ve barely said a word about Nelson’s songs or his singing (see my last post for a few thoughts I have about that; there are likely to be several more in the future). I haven’t mentioned his legacy as it’s been established and forecast in the countless cover versions of Nelson’s songs, the tributes to him (I was planning to talk about last year’s 90th birthday concerts, but that too will have to wait for another occasion), the ways his talented children take his and their own music forward (I’ll pop a couple of videos below), the ways he has reckoned with age and mortality in his late work, the worry us fans have every time we hear about health setbacks, and so on.

I’ll have fewer words than this to use in my fifteen-minute presentation to the gerontologists next Thursday (when hopefully Willie, back to full strength, will be playing his umpteenth 4th of July concert), so will need to find something to cut out (perhaps Willie, a master of concision, can inspire me). What I hope to get across are three main points about how ageing musicians offer ways for audiences to reflect on age, time and experience:

Lyrics in songs about ageing, memory, evocative objects (I haven’t touched on that so much here, but will do on the day).

The songs themselves as evocative objects that accompany listeners through their lives, providing historical and biographical landmarks (that should be obvious from the comments left in response to that photograph).

The awareness of musicians as longstanding figures/friends/reference points and mirrors for audiences to recognise their own ageing.

Some videos

I usually include music examples in my posts. Here are some that are relevant to all of the above.

The Rolling Stone documentary on Trigger:

A two-part interview with Mark Erlewine, the ‘Trigger Doctor’ featured in the RS documentary:

Lukas Nelson performing ‘Angel Flying Too Close to the Ground’ at last year’s 90th birthday concert at the Hollywood Bowl2:

Micah Nelson performing ‘Die When I’m High (Halfway to Heaven)’ at the 90th birthday celebration:

Lukas Nelson standing in for his ill father on the Raleigh, NC, leg of the ongoing Outlaw Music Festival Tour on 23 June:

Willie and Lukas Nelson duetting on Lukas’ ‘No Place to Fly’, another angel-themed song that seems to be partly about time and age and partly about the everyday (which is how we experience time and age, after all). This was probably the first song where I really felt the deepening of Willie’s voice with age, due mainly to the way Lukas’s voice fills in the higher register I’d have associated with his father’s younger voice.

That idea of a singer as a kind of healer is echoed by Nelson in a comment on ‘Healing Hands of Time’ in his 2023 book Energy Follows Thought. Talking about Ray Price, who recorded the song in 1966, Nelson says, ‘Ray was seven years my senior. He had wisdom I lacked, not only as a man but as a singer. Just as he had deepened “Night Life,” “I Let My Mind Wander,” and “It Will Always Be,” he took “Healing Hands of Time” to another place. He took the song beyond time. He understood that time is flowing energy and if you go with the flow your worst wounds will mend. That certain knowledge is all in Ray’s voice. As much as in the lyrics, there is healing in the sound of Ray’s voice’.

I want to write about uncanny voices and guitars in this and other Lukas Nelson performances at some point in the future. Please hold me to this.

I think the sepia and black and white are inspired by those old west photos of Edward S. Curtis, and with Willie's, there is a clear influence from Curtis’ photos of Native Americans. Also possibly Solomon Bibo.

I love the photo of the hands. For an artist, they are the tools that create the art. Same with the feet of ballerinas. I also love the idea of how somebody who works with their hands, say Willie, Lucien Freud, or even a metalworking mechanic, compares to the hands of somebody who has never used them (the Queen's aging hands would have looked nothing like Willie's).

Wonderful article, as always, Richard. It was a nice read on a sunny morning in beautiful Arequipa, Peru, as I nurse my foggy Pisco head.

The connection of music and aging is a rich one, there are any number of ways to connect and this is a nice tribute.

It occurs to me that, for all of the ways that people can lose physical skills and abilities as they age playing music is often one that can be maintained (though I also have a sense that many musicians at some point in their career have to learn how to manage tendonitis or posture problems imbalances that can come from carrying or leaning over an instrument for so long).

But I will take a moment to share one store about music and memory that just happened recently. Many years I'd found a video on youtube of someone singing a sea chanty with a couple of co-workers in a back room in their office. Part of what made it interesting was the way it demonstrated the legacies of the British empire, with an American and two people from the Indian subcontinent singing a song from the age of sail.

I had been looking for it, and unable to find it, and didn't have much hope -- that description, while clear, doesn't offer much use in searching for it. But then, at some point, I was looking for something on Mainly Norfolk and reading one article I thought, "wait, that's it, that's the song they were singing in the video over a decade ago." https://mainlynorfolk.info/folk/songs/stormalong.html

And, indeed, it was -- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VyMODqEYARE

It was an interesting demonstration of the way that music can trigger memories; in that moment it just came back.