Is it true that no one wants to read long posts? I’ll keep this one short.

Is it true that readers don’t want images, videos and other non-text clutter? I’ll leave them out this time. Perhaps just one video to round things off below?

When I say I’ll keep this short, I mean short for me. Many of my Substack posts are 2000-3000 words. I’ll keep this to under 1000.

(If that’s still too long, here’s a TLDR link to the end of the post, the bit where I claim that ‘Brass Buttons’ by Gram Parsons is a great example of brevity.)

Reading Substack discussions on ideal post lengths got me thinking about how I’ve always been drawn to long form, and not only in writing.

Never much of a sportsman, at school I ‘chose’ running rather than team sports like football, rugby and cricket. It was long distance running that I endured enjoyed. It seemed the best option for me when there was no opt-out from physical activity.

I was good at running. I ran for the school and got results. As a teenager, I ran a half marathon and won a trophy.

When books started to dominate my life, I read novels rather than short stories. There were exceptions: I became fascinated by Jorge Luis Borges at a precociously young age. (Fascination and understanding are separate things. Why was Labyrinths in the school library unless they expected schoolkids to at least try?)

Although I started buying singles, it wasn’t long before albums became my go-to format. I tended to favour longer LPs, though there are many brilliant short albums. Always worth a thread: classic albums under thirty minutes long?

I don’t think this was about value for money. I suspect it was more to do with immersive listening. Otherwise, I wouldn’t have got so annoyed with the trend to reissue single albums that used to play at 33 1/3 as doubles designed to spin at 45. That seems to be connected to a vinyl-wasting fashion with new albums to put less than fifteen minutes of music on a side.

When I started making mix tapes, I preferred C90s to C60s. More music, richer narratives. Streaming platforms like Spotify have been a disaster/blessing, with my year-end playlists typically hitting the six-eight hour mark (evidence: 2023, 2022, 2021).

At university my essays were over length, my plans for them too ambitious. An American History lecturer told me that one of the things I was there to learn was discipline. I remember thinking, ‘If I’d wanted to learn discipline, I’d have joined the army’. Now I’m a university lecturer who frequently tells students that they need to be more disciplined in their thinking.

Never the chattiest of men, in conversation I often embark on long narrative tangents. I’ll see people’s eyes glaze over as I head off on another detour. Alternatively, they’ll just speak over me to try and animate the exchange or get to the point. (In my head, the point always requires more context).

My lectures tend to overrun and have too much information. Mostly, my students are polite enough not to tell me that I need to be more disciplined in my lecturing.

When I started to publish, I gravitated towards books rather than articles. I still tend to feel that it’s only books that allow me to follow the connections and parallel tracks that I find so interesting when thinking about things for a while and in depth.

As a writer, I often ask editors for permission to go over requested lengths. Here at Substack, we don’t have editors, which is another of those blessing/disaster situations.

Substack is, for me, an exercise in brevity. I task myself with offering an essay a week. But length is relative and, for Substack, my posts are probably too long. I get the reasoning behind posts like the one I linked to at the start. We have little time. We’re inundated with information. Too much waffle. Pull me in and get to the point.

What might I learn from songs, given that songs are what I mainly write about?

Songs are probably the things that remind me most often of brevity’s potential. I like many long songs but I listen mainly to short ones. I think of them as perfect miniatures.

Earlier this year, Michael Fell wrote eloquently about how less is more, using Nick Drake’s just-under-two-minute song ‘Road’ as an example. I could name a hundred more, but won’t (brevity, remember).

Examples abound in many genres. I’ve always admired country music’s condensation. There are so many classic country songs with minimal lines and short running times. ‘Three chords and the truth’, as Harlan Howard would say.

‘Brass Buttons’

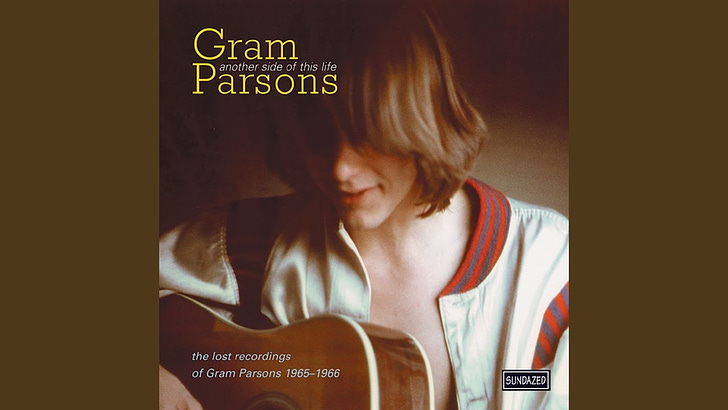

I’ve written long posts about how songwriters use lists in their lyrics to evoke characters, events, feelings and more. Some of the lists are long too, but I’ll conclude this post with a list from Gram Parson’s ‘Brass Buttons’ that I think offers a brilliant example of brevity: ‘Brass buttons, green silks, and silver shoes / Warm evenings, pale mornings, bottled blues / And those tiny golden pins …’

The version above isn’t my favourite. Parsons’ trademark fragility is there in the vocal, but the guitar seems too frenetic. The better-known version, released posthumously on Grievous Angel, remains definitive. A slower delivery and what I think of as the ‘luxury bedding’ of James Burton’s guitar, Al Perkins’ steel and Ron Tutt’s drums.

I posted Parsons’ earlier recording because it’s shorter than the one on Grievous Angel (2:25 vs. 3:30). There’s an even shorter version by Johnny Rivers from 1970 that delivers in 2:06, due largely to Rivers cutting half the lyrics: not the best way to do brevity, perhaps.

If the extra minute on the ‘official’ ‘Brass Buttons’ is padding, it’s beautiful padding. I wouldn’t be without it. And I still think of the longer version as a perfect miniature because of that evocative list.

I’d like to write like that.

Nice post, Richard, and Gram Parsons--sigh--so amazing. But really, I just came here because a friend sent me this, and I thought you had to see if you haven't already.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rSXoM0WIUUg

Your thoughts on brevity strike a chord. I too write at length - my longest essay on Substack clocked in at 6,000 words or so - and while I know that my approach is doing everything you are not supposed to do when writing online, I feel a glee at bucking the trend and gratefully finding an audience for my work. The great thing (maybe the greatest) about Substack is that it accommodates writing of all kind, and I delight in those who opt to writing long-form essays (while appreciative of those who write more judiciously and briefly).