Auburn Hair, AI and Afterlives: ‘Jolene’ as Song Object

Songs about objects are often really songs about experiences, but these are experiences mediated through objects: both the objects the songs are about and the song as object.

This week I taught a class on my ‘Case Studies in 21st-Century Music’ module about music and AI. My students and I considered celebratory and anxious narratives around AI, surveillance capitalism, digital selves and ‘non-things’. We also thought more generally about music’s materiality and virtuality and considered whether music’s always been a kind of virtual reality and perhaps a form of artificial intelligence.

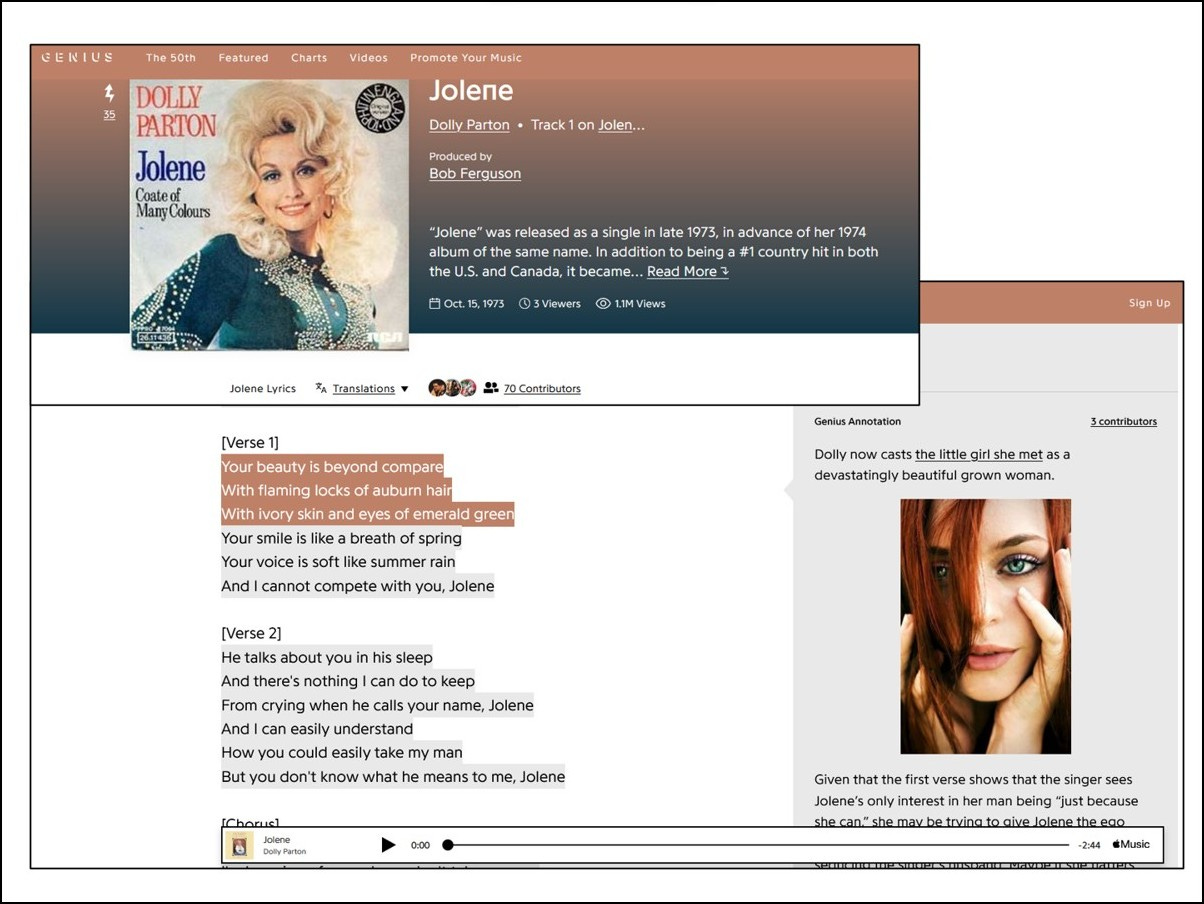

It was the second time I’d taken this class and, as I did one year ago, my introductory case study was the cover version of the Dolly Parton classic ‘Jolene’ by Holly Herndon in the guise of her digital/deepfake ‘twin’ Holly+. When we studied the case study last year, it was new, having been released on 31 October 2022 (Halloween). It was interesting to come back to it a year later and see what the new students made of it.

The Holly+ version of ‘Jolene’ is the starting point for this piece, too, though I’m not focussing solely here on what it might tell us about AI. I’ll come back to that later but first I want to follow a set of thoughts about songs and objects that were prompted by the Holly+ release.

In taking this approach to the song, I’m echoing what I’ve done with other songs I’ve written about in my academic work, where I use the life of songs—or what I sometimes call song biographies, song itineraries or song trajectories—to see where they’ve been, where they might take us and what their journeys might reveal. It’s a technique I’ve used in various ways before and which I hope to write about more in the future.

I also want to acknowledge the influence on my thinking here of my PhD student James Barker, whose thesis on Dolly Parton has recently been submitted for examination. It’s a work that considers the trajectories of many Parton songs, including ‘Jolene’, and examines their role in creating a sense of belonging in country music for LGBTQ+ listeners and musicians (see, for example, James’s accounts of ‘Coat of Many Colors’ and ‘Jolene’).

Holly+ and ‘Jolene’

Holly+’s ‘Jolene’ was audiovisual from the start, with a video featuring a 3D digital model of Herndon/Holly+ performing the song in what Rob Arcand, writing for Pitchfork, called ‘a glitchy pastoral world filled with old trucks and farm houses’. The Halloween timing of the release no doubt played a part in the responses by some online commentators that focussed on the ‘creepy’ and ‘uncanny’ aspects of this song object.

Responses from YouTube commenters were initially positive, with several praising Herndon’s inventiveness, though some online responses were quick to connect this new venture in AI to questions of ethics and copyright, echoing concerns raised more broadly around the quickly evolving field of AI-powered image, text and sound generators.

Accompanying the release of the single were several online features that provided accounts of how the song was created, presumably based on information included in press releases. The following from Matt Moen at Paper is a typical example:

The stripped-down cover was made by feeding a modified score into Holly+ with new harmonies. The result was then generated into Herndon's own voice. Featuring additional accompaniment by Ryan Norris on guitar, the cover is truly impressive in its uncanny likeness, being able to seamlessly reproduce Herndon's dynamic vocal range without wavering.

In an article for Dazed, Serena Smith quoted Herndon on the motivations for using this particular song as a way of testing out the Holly+ technology:

It felt interesting to cover Dolly for a few reasons. I’ve been exploring the idea of Identity Play (IP), or using AI to be able to perform with or as someone else, and Dolly's music means a lot to me as we are both from Appalachia. This is the kind of song I would never dare to sing with my natural voice. She is a fantasy figure for me.

For me, Holly+’s ‘Jolene’ prompts a range of questions not only about AI-generated pop, but also about the status of songs and the objects they both use and become. What might this song and video have to do, for example, with the anxiety over a move from a world of things to a world of information, or what the philosopher Byung-Chul Han calls ‘the infosphere’? And what implications does it have for the hallowed tradition of the cover version?

Song objects

As my previous posts on Songs and Objects have started to outline, I’m interested in songs as technologies for placing objects in our consciousness. That goes for both the objects that songs are about (what they bring to lyrical life) and the songs themselves, which enter our lives as objects that we cherish, dismiss, become addicted to, live with, fall in and out of love with, return to, recall or have recalled for us. There is the content of songs and there is the form of songs, their lives, afterlives and itineraries.

As I wrote in an earlier post about ‘songholders’, these interests of mine can be summarised as ‘what songs do with objects’ and ‘songs as objects’. Another interest is ‘what objects do with songs’, with some of those objects being human and some not. Holly+ would fall into my category of ‘nonhuman songholders’. So would YouTube, Spotify or wherever else we might go to encounter the digital code that we recognise as ‘Jolene’.

From a brief consideration of the lyrics (available all over the web), it seems clear that Jolene is an object in the song. She is an object made of auburn hair, hazel eyes, ivory skin: all these are objects too. Jolene is an object of desire for another object, the unnamed male character, who talks about her in his sleep. She’s an object, too, for the singer, who is obsessed with Jolene’s beauty and what it threatens.

These are all song objects and the song itself is also a song object.

How the objects relate to each other and to the subjects who engage with the song has been a much-explored topic. There’s a fascinating episode of the podcast Dolly Parton’s America about ‘Jolene’, which looks at the character relationships within and outwith the song and offers fresh perspectives about who is singing to and for whom.

Much of the narrative around the song has been about who Jolene is, who the singer is, who ‘my man’ is, and what the motivations for writing and performing the song might be. What I’m interested in here, though, is the life of the song: not so much Jolene (the character) as a song object, but ‘Jolene’ (the song) as an object.

Songs generate things

Songs have biographies or afterlives; they travel on itineraries. Songs are generative too, creating new things in their wake.

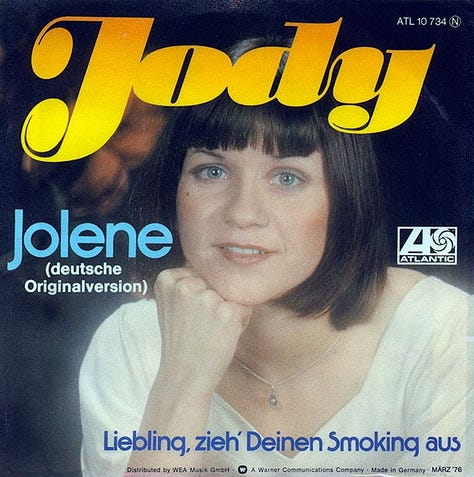

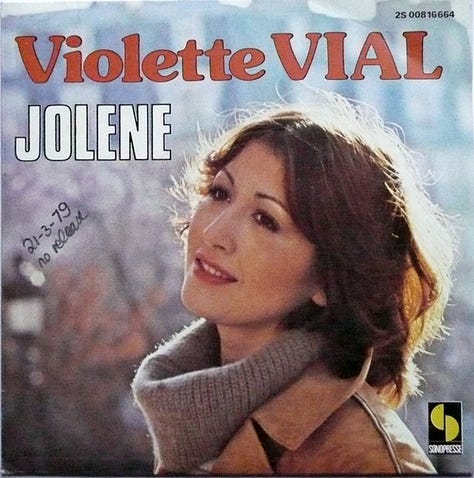

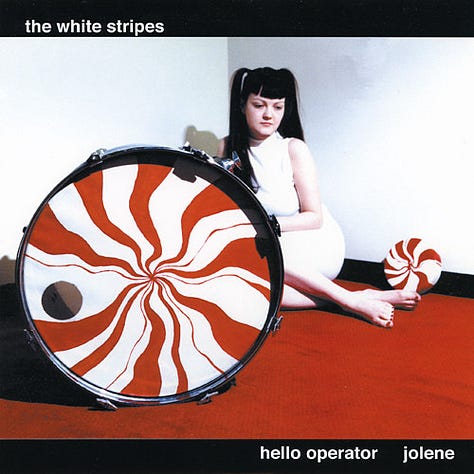

Of the many things that songs can generate, one of the most obvious perhaps is cover versions. The website SecondHandSongs lists over 200 versions of ‘Jolene’; there are even more on Spotify and other platforms. One of the fascinations of scanning the list at SecondHandSongs is finding renditions in other languages, for example Agnes Chan’s Cantonese version from 1979.

There are also French, German, Dutch, Finnish, Swedish and Brazilian ‘Jolene’s, as well as multiple Czech versions, including Jan Nemejovský’s rewriting of the song as ‘On Ví’ (He Knows) for the late Naďa Urbánková.

Thinking about cover versions is itself generative, raising questions about ethics, copyright, aesthetics and much more. What makes a good cover? How much change do we expect from the ‘original’? How much can the content of a song be altered for it to still be recognised as that song? What is the role of familiarity? What happens when the language changes?

Remix is another way that song gets mutated while still being recognisable and ‘Jolene’ has been reshaped by Todd Terje, Freejak, Real Hypha and many more. Jad Abumrad, host of Dolly Parton’s America, created his own remix for the show. As well as suggesting yet more ways in which the song’s objects—its lyrics, vocals, instrumentation, groove and vibe—can be redeployed, Abumrad’s version also echoes the quite significant intercutting of audio sources that distinguishes the sound world of his and many other contemporary podcasts.

Elsewhere, Jolene gets the chance to change from object to subject in a range of songs written as responses to Parton’s original. Examples include Kirsty Maccoll’s ‘Caroline’, Esme Patterson’s ‘Never Chase a Man’ and Jennifer Nettles’s ‘That Girl’, all written and performed from the perspective of Jolene herself or a woman in a similar position.

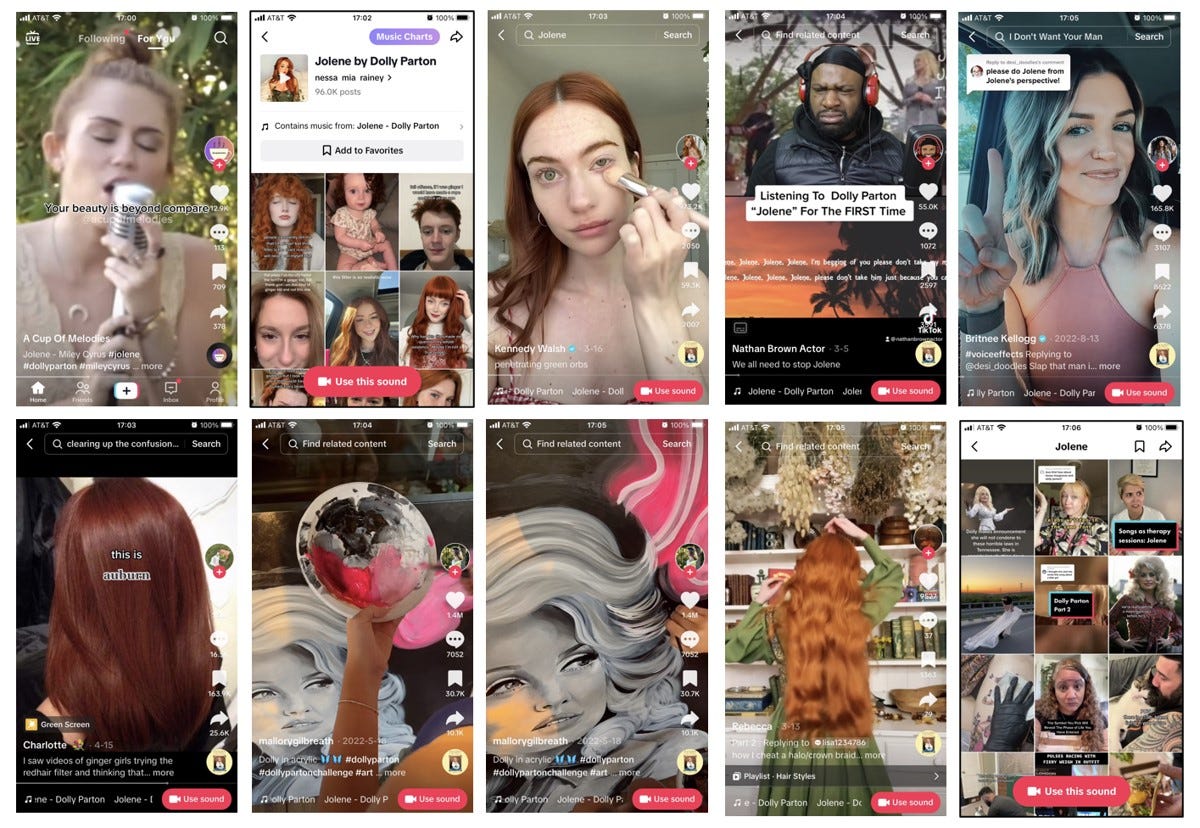

When preparing a paper inspired by the Holly+ rendition of ‘Jolene’ in June of this year, I decided to see what came up when I entered the song’s title into TikTok and explored the ‘use this sound’ feature. I guessed there would be a lot more objects generated by the song and I wasn’t disappointed.

Among the many things that TikTok users have done with ‘Jolene’, the most common videos seem to have been makeup tutorials for getting the ‘Jolene’ look, posting about hair colour or writing response songs from the position of Jolene. These videos can be connected to longer histories of fan art, work generated by fans in response to aspects of their favourites artists’ styles, personas and music.

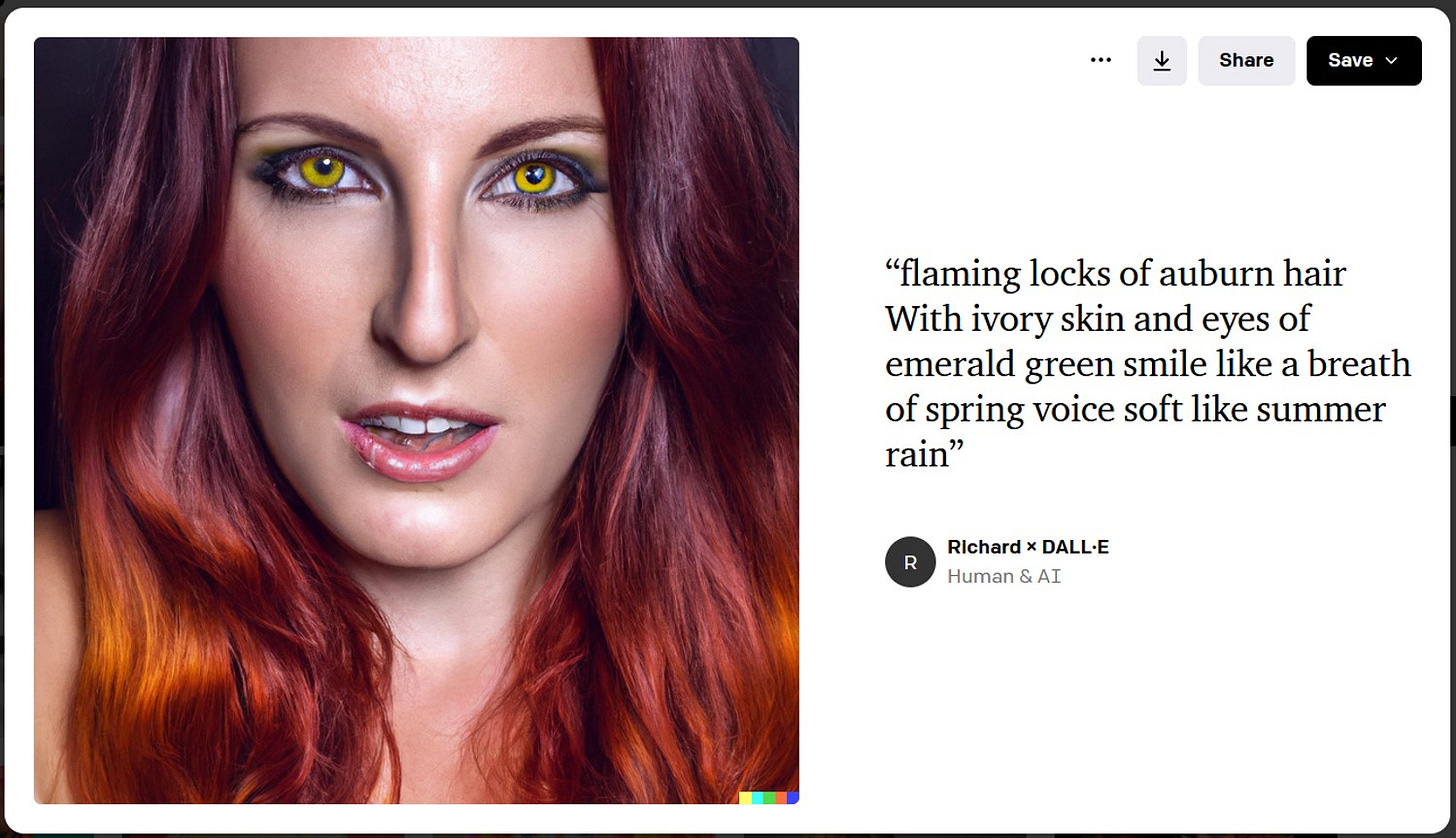

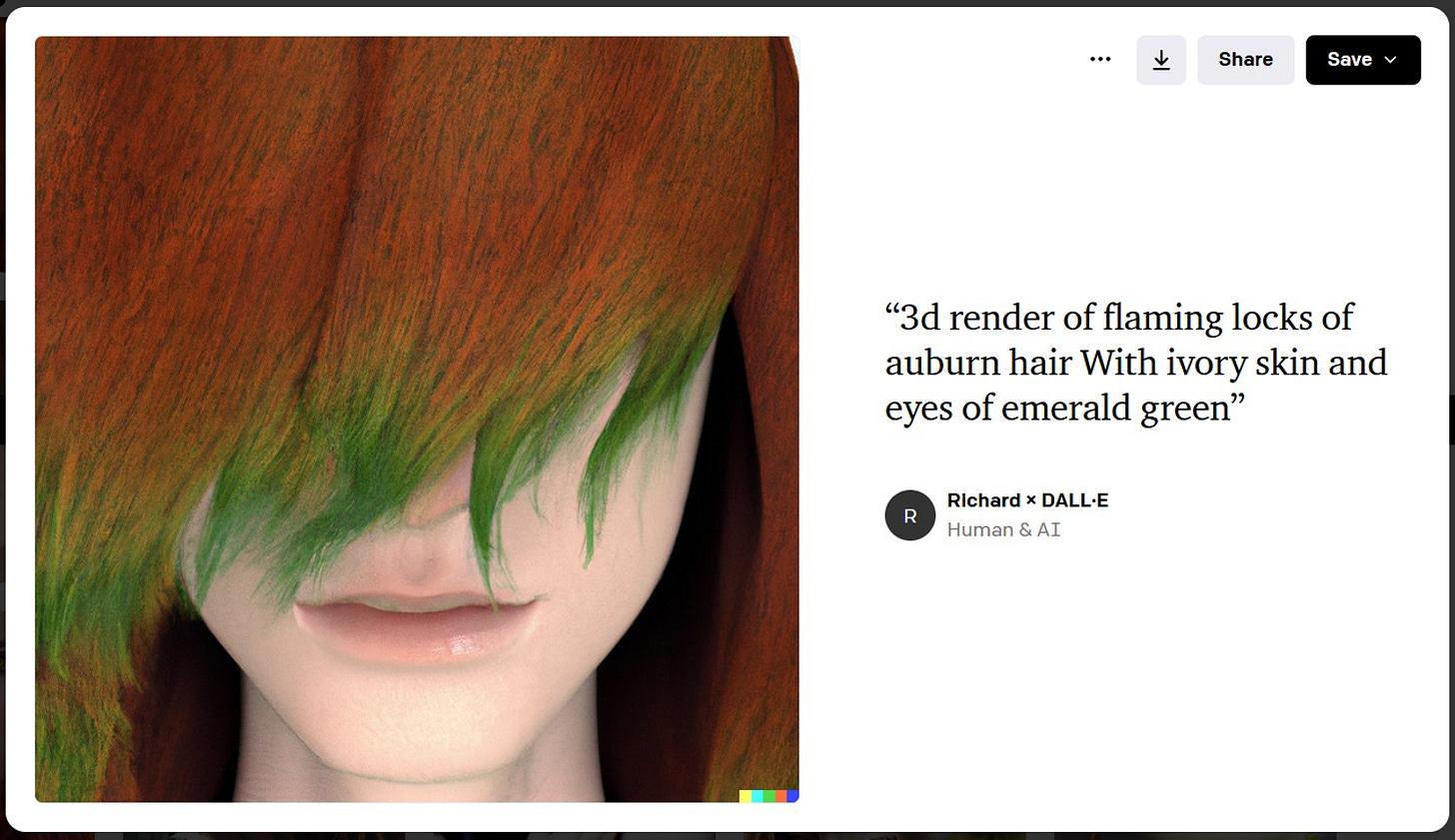

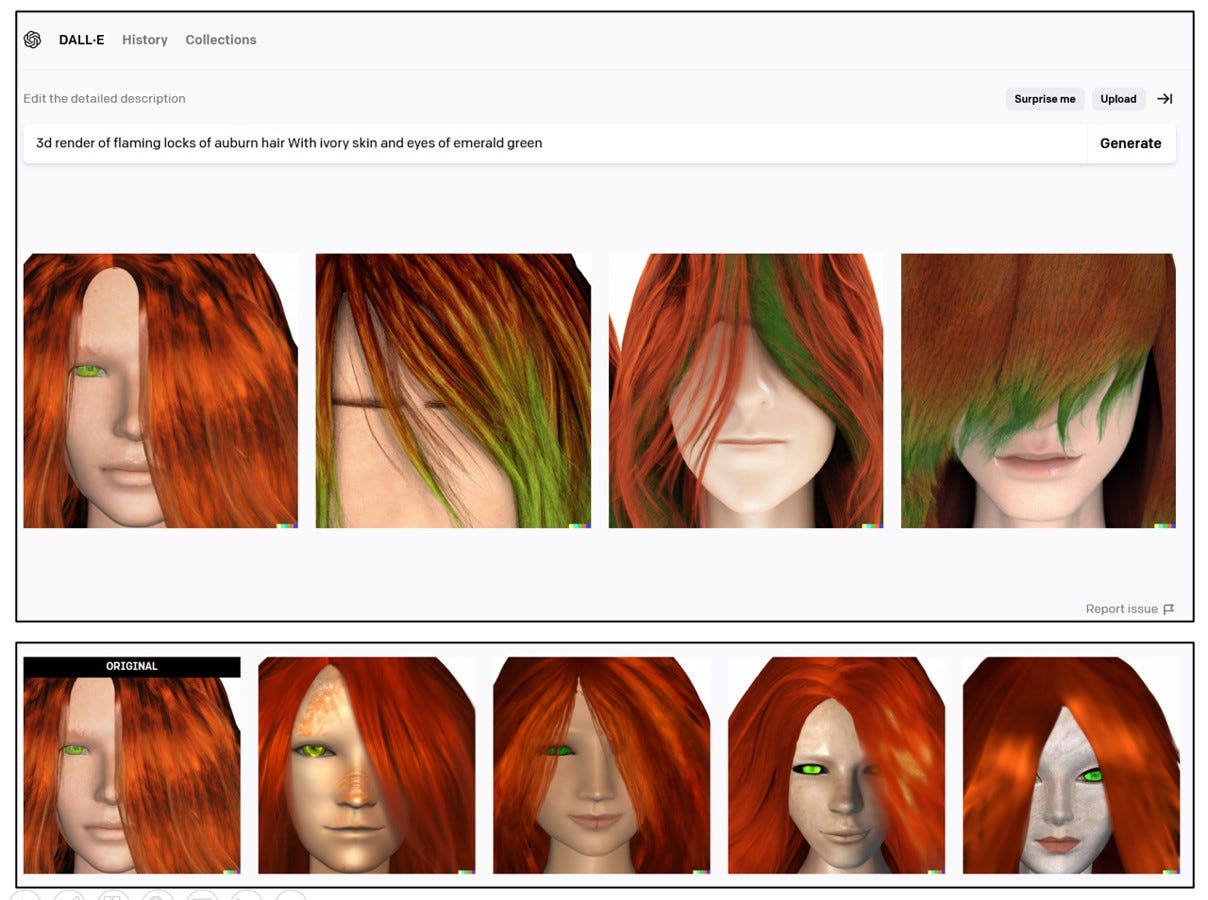

Thinking about another contemporary spin on fan art practices, I fed some of the object-oriented lyrics of ‘Jolene’ into the text-to-image AI programme DALL-E as a prompt.

I also plugged the lyrics into ChatGPT to try and generate a conversation but it just told me how well I was evoking the lyrics of the Dolly Parton classic ‘Jolene’ and gave me a brief summary of the song’s lyrics.

Those rabbit holes are potentially endless, so I pulled back to some other ‘Jolene’-related texts I was aware of.

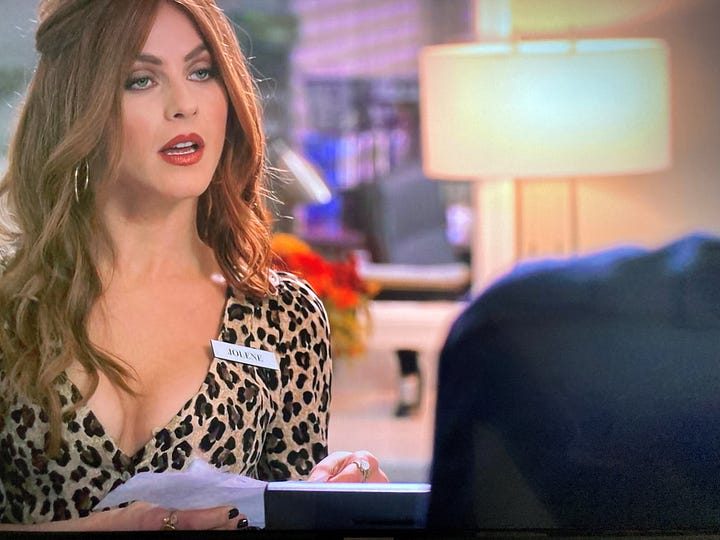

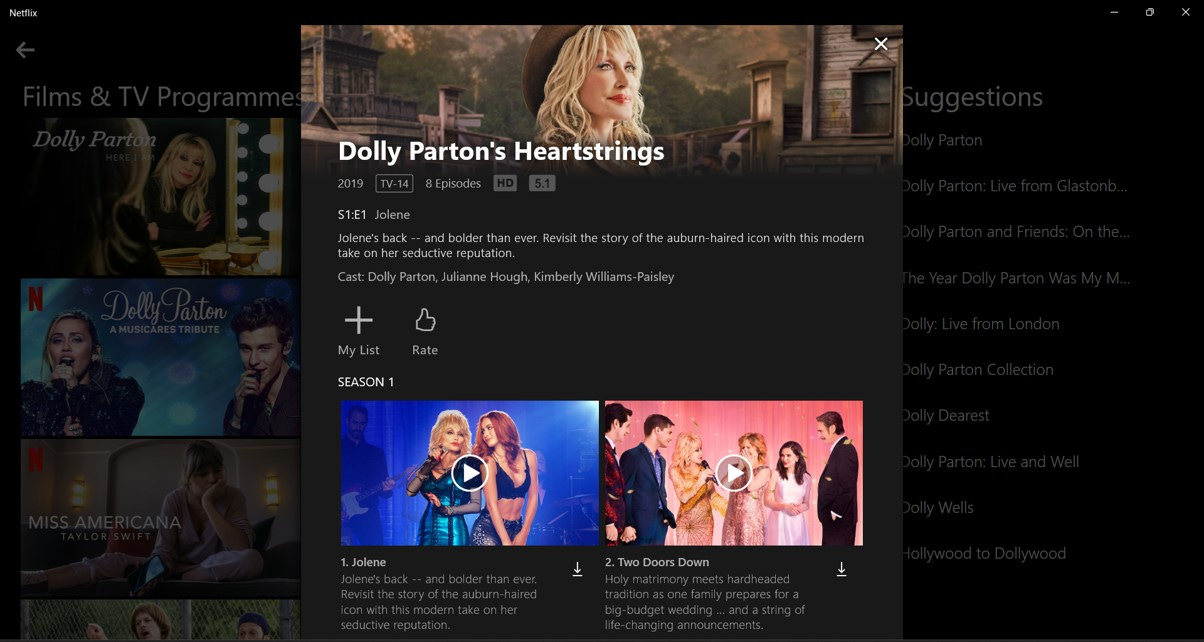

The song has been responded to in other ways on film and television, for example in an episode of the Netflix series Dolly Parton’s Heartstrings and as a recurring feature in drag queen shows (its presence as a drag staple is not limited to the screen, of course).

Parton has in turn responded to the drag legacy by performing an alternative refrain from her famous song, replacing ‘Jolene’ with ‘drag queen’.

It’s a reminder that refrains are song objects too, part of what makes a song so recognisable. Refrains generate new refrains, a practice popularised in appropriations of songs by sports fans and protesters. As well as the ‘drag queen’ version, Parton has used a ‘vaccine’ version in response to Covid-19.

Experience

Songs about objects are often really songs about experiences, but these are experiences mediated through objects: both the objects the songs are about and the song as object.

Then there are the objects that songs get attached to and which I think of as human and nonhuman songholders.

In the world of popular music, we tend to receive songs as telling us something about the singer or songwriter ‘behind’ them. To do this we often rely on notions of experience, biography or back story. This is true of the original ‘Jolene’. Look the song up online and pretty much every piece of explanatory writing will tell you that Parton was inspired to write the song by encountering an auburn-haired bank teller flirting with her husband and/or signing an autograph for a young girl called Jolene and finding the name attractive for songwriting.

The details of the relationship between the teller, the child and the character of Jolene as represented in the song will vary with each telling, but the main thing seems to be that there’s a story to tell that connects the song to Parton’s life. This is also true when people offer alternative readings of the song. The ‘Jolene’ episode of Dolly Parton’s America, for example, features musicologist Nadine Hubbs adding an extra verse to the song to bring out the possibility that the singer is attracted to Jolene herself. Again, such a reading relies on the importance of back story, on what we know, or think we know, or would like to know about Dolly Parton.

The response songs that have been written after ‘Jolene’ also root their relevance in notions of experience. Esme Patterson has spoken about the motivation behind her Woman to Woman album (which contains her song based on Jolene’s response), saying that she wrote the songs out of a sense of frustration with how female characters were presented in songs.

So too with Holly+ and the 2022 ‘Jolene’. However well listeners think it may compare to other versions, it would probably not have caused much attention as yet another cover of a classic song were it not for the way it was created. That seems to be the whole point of the story.

Experience and biography, then, are crucial to how we connect song objects to songholders, to real people and their lives. That is doubtless why, in books and articles I’ve pubished previously, I have tried to listen to the ways singers, songwriters and listeners use the voices ‘behind’ the songs to reveal aspects of their lives and experiences.

This line of thinking would seem to go along with what some academics who write about music refer to as ‘musicking’. This term, coined by Christopher Small, is used to argue that what people do with music—music thought of as verb or process, in other words—is more important than the idea of music as a ‘thing’ to study in isolation.

Does this emphasis on experience move us away from the song object, then? Do we move back along that spectrum from music as thing to music as process? No doubt we do, but my point remains that we are still relying on song objects to do that. Processes and experiences and musicking all require objects in order to happen.

In an article about the various afterlives of ‘Jolene’ and what the song has meant for ideas of LGBTQ+ community, James Barker writes:

Treating ‘Jolene’ as a text with this kind of sociability shifts the spotlight from Parton herself and refocuses the emphasis within scholarship from reifying country stardom’s white and heteronormative biases onto the active participation of LGBTQ+ artists and audiences.

This emphasis on community and on finding different meanings for a song object strikes me as a way of reconciling things and processes. Similarly, I don’t see any contradiction with thinking about music as a collection of things while also thinking of it as something that people do, take meaning from and build community around.

Nonhuman coda

What of songs’ own lives, though? What about the ways they are able to travel, seemingly as it thay had their own agency, separate from those musicking human beings looking to do things with them?

In his book Non-Things, Byung-Chul Han writes:

We no longer inhabit earth and dwell under the sky: these are being replaced by Google Earth and the Cloud. The terrestrial order is giving way to a digital order, the world of things is being replaced by a world of non-things – a constantly expanding ‘infosphere’ of information and communication which displaces objects and obliterates any stillness and calmness in our lives.

Songs as recordings—in other words, as the kind of things that encourage all the examples I’ve mentioned above to happen—are examples of the infosphere, of how things can become non-things. All those versions of ‘Jolene’ out there, available to many of us via a few clicks, are all just so much information. It’s no wonder that bots are being trained to feed off online tracks and to create fake new tracks that spread like viruses though the infosphere.

Has song modelled all of this before for us, even prior to AI? Was song itself always a form of artificial intelligence, a herald of what Christopher Bollas calls ‘the unthought known’?

Song as AI, as something generative but also as something sourced from the extrahuman: what would it mean to pursue that idea, to ask where song comes from? Or to ask the question that musicologist Lawrence Kramer asks: what do songs want? How might thinking of song as AI move us away from historical—and some might say patriarchal and colonial—notions of authorship?

This is all part of the discourse prompted by nonhuman songholders. If music predicts the future, as theorists like Jacques Attali have argued, then it’s not so a much a question of whether nonhuman songholders could really operate without some kind of human involvement (whether at the production or consumption end), but rather of how so many musical examples make it so easy for us to imagine such a possibility.

March 2024 update: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=x9XHMK3nWr4