A song can be a shawl worn by a mourner. A tear can become a fetish, something longed for and something that can never be captured. A fado song can be a beam of moonlight, exposing hidden presences while creating new shadows, doubts and absences.

The death of Amália Rodrigues in 1999 made news nationally and internationally. In Portugal, three days of national mourning were announced, and many newspaper and magazine articles reported on the late ‘queen of fado’. Outside the country, there were obituaries, feature articles and, soon, the release of compilation albums and audiovisual tributes to Amália.

Among those paying homage was Mísia, the Portuguese-Spanish fado singer who had begun her recording career in the 1990s. Along with Dulce Pontes, another young singer whose cosmopolitan song choices ventured beyond fado while usually circling back to it, Mísia was an early example of what would soon become known as ‘novo fado’. She brought to the genre a sense of visual style that had been missing since Amália’s heyday, appearing in concert and on her CD covers dressed in haute couture outfits that recalled fado’s past—shawls, dark colours, dramatic gestures—and its present in a world of fashion photography, light shows and music video. As Amália had done, Mísia highlighted the work of many of Portugal’s most notable poets in her choice of fados, setting them to newly commissioned music.

While Mísia paid homage to Amália from early in her career, her 2001 album Ritual was more explicitly directed toward the late fadista in that, as well as including songs associated with her, it added a song written in her memory (‘Xaile de Silêncio’) and an arrangement of Rodrigues’s unrecorded poem ‘Vivendo Sem Mim’.

This ‘Amálian’ angle accounts for part of the ritual of the album’s title, though there’s also a more general nod to fado as an ongoing ritual of practice, a way of living and making music. In an interview published in 2007, Mísia told the French journalist Hervé Pons that she wanted to celebrate the world of amateur fado with Ritual:

I dedicated a disc to the small world of fado, because, no matter what people might think, it is those zealous amateurs who maintain the ritual and perpetuate the tradition. Fado with a capital ‘F’ is not Amália, Mísia or Mariza; it is this river of anonymous souls who play and sing in the tabernas. It’s the mechanics, lawyers, seamstresses, merchants, fishmongers, primary school teachers, nurses and office workers who get up in the semi-darkness of the vaulted basements and sing for friends, onlookers and lost tourists. For me, it’s them who keep fado alive, not the commercial enterprise of ‘novo fado’, which like all trends is bound to die. Fado of the street has this immortal quality: being new every day rather than being fashionable!

Notwithstanding this admirable intent and the concern over fado becoming faddish in the hands of a new generation of recording artists, Ritual created an object that could be disseminated far and wide and that can still be returned to. Indeed, it stands up well a quarter of a century after its recording, as does Mariza’s debut album from the same year.

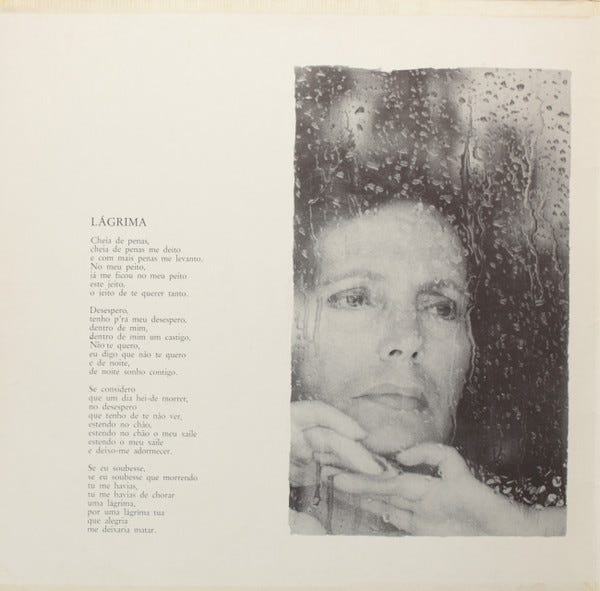

It’s the songs that dwell on the Amálian legacy that I want to consider when exploring fado’s objects of longing. First off, ‘Lágrima’, the astonishing poem written by Amália and set to music by the guitarrista Carlos Gonçalves. Amália recorded it on an album of the same name released in 1983.

As I described it last year, in my piece ‘Sixteen Song Moments’, ‘Lágrima’ is ‘a song of despair, unrequited love, the dream-world and death’. It offers up a protagonist who is desperately hoping that the object of their desire might finally notice her, might finally offer up a sign of emotion if she were to die. For a single tear, she’d happily cease to exist.

We are clearly in the presence of despair, so it’s little surprise the word appears in dramatic form at the start of the second verse, ahead of a thwarted attempt at self-denial:

Desespero Tenho por meu desespero Dentro de mim Dentro de mim um castigo Não te quero Eu digo que te não quero E de noite De noite sonho contigo Despair I have my despair Inside me Inside me a punishment I don't want you I say that I don't want you And at night At night I dream about you

Here’s Amália singing that verse:

Here’s Mísia singing the same verse on Ritual:

I want to highlight this verse partly because I dwelt on the first and fourth verses of the song in last year’s post on song moments, and partly because there is another song on Ritual with the title ‘Desespero’, marking despair as something of a theme for the album. It’s a great mournful mouthful of a word to sing.

The object given the most pathos in ‘Lágrima’, however, is the titular tear drop, the sign that love or something approaching it might be returned. Consequently, it gets the prime position near the end of the song, where it’s also repeated in typical fado fashion. I don’t know of an interpreter who doesn’t make the ‘lágrima’ the object the singer has been working towards, however expressive the delivery of the earlier verses.

It’s not the song’s final word. That honour is reserved for ‘matar’: to die.1 The song dies, or is killed, almost immediately after that word is sung, the guitars quickly bringing the executioner’s blade down. But ‘lágrima’ remains the pivot of the song’s final stretch, the word it all hangs on.

Here’s Amália’s delivery of the line, in one of the clips I shared last year:

And Mísia:

Another highly singable, songful word is ‘xaile’, the Portuguese word for shawl. It appears in the third verse of ‘Lágrima’, when the singer says that she will lay out her shawl on the floor and let herself sleep. For Pascale Petit, who provides an English translation of the song in Saudade: An Anthology of Fado Poetry, ‘it is as if this shawl is the longed for single tear wrung from the unfeeling lover’.

A shawl stands in for a tear, just as shawls have often been symbols of mourning. Amália popularised the wearing of a shawl during performance as a gesture to Maria Severa, the nineteenth-century ‘mother of fado’ who died in her twenties. Mísia followed suit and could often be seen donning a shawl prior to singing, as in this rehearsal video for the last album she released prior to her own passing last year.

The song ‘Xaile de Silêncio’ originated as lines sent to Mísia by the poet Mário Cláudio on hearing of Amália’s death. The central metaphor, the shawl of silence, is what the late diva has left her audience. Perhaps it’s what has been left upon the ground in the wake of her passing. It’s a symbol of mourning, of course, but also an object associated with Amália’s self-presentation and, as we’ve seen, her lyrics.

Cláudio lines up more objects from the legacy in his verses: ‘a strange way of living’ (in reference to Amália’s classic fado ‘Estranha Forma de Vida’); ‘the shadow of lovers on the corner’ (more timeless fado imagery); ‘the flight of the most perfect seagull’ (recalling the ‘perfect heart’ and the seagull of another Rodrigues signature song, ‘Gaivota’). These all become objects of longing and memory, traces of the person whose absence is felt.

Wrapped around them all is the silencing ‘shhh’ of the xaile, the shawl.

The music for ‘Xaile de Silêncio’ was provided by Carlos Gonçalves, who had been Amália’s composer and accompanist during the last stage of her career and who composed the music to ‘Lágrima’. Gonçalves also acted as guitarrista and musical director for Ritual, providing another important continuation of the Amálian legacy.

‘Mistério Lunar’ is a poem by João Monge. The version on Ritual uses music by the guitarrista Armandinho that Amália had sung with different words, as ‘Fado Mayer’, in the 1950s. Monge’s lunar reference finds a correspondence with other moonlight-referencing songs on Ritual—’Duas Lunas’, ‘Cor de Lua’ (which also mentions a shawl), the ‘lap of the moon’ in ‘À Beira Da Minha Rua’—and contributes to a saturation of metaphors throughout the album connected to night, shadow, darkness, light, absence and altered realities.

There’s even something of a woman-in-the-moon quality to some of the pictures in the CD booklet.

‘Vivendo sem Mim’ is a poem written by Amália, published in her book Versos but not recorded by her. On Ritual, it is put to music by Mário Pacheco and performed by Mísia and the pianist Christian Boissel in a manner that evokes Amália’s rehearsals with Alain Oulman in the 1960s. The title translates as ‘Living without Me’ and so has obvious connections to the absence left by Amália’s passing. The lyric is full of fragments that shift between clarity and abstraction. There’s a mention of the moon again, and of lessons learned over the course of a life. There are observations, or memories, of a little girl, a ‘Spring flower’ who was given ‘the fate that was already yours’. Such themes recur in Amália’s poetry and interviews, as does the memory of lessons learned. In ‘Vivendo sem Mim’, those memories punctuate throughout: ‘they told me the sky … they told me love … they told me God’.

‘Mistério Lunar’ and ‘Vivendo Sem Mim’ work as a pair. By putting new words to a tune Amália sang and new music to words the great fadista wrote, Mísia suggests the ways in which fado’s ritual might proceed. The ritual extended beyond the song texts to the recording process too, with the use of valve microphones and single takes to emulate recording practices of the 1940s and 1950s.

In her interview with Pons, Mísia highlighted Amália’s awareness of song and poetry as sources of learning. ‘Once, during a concert, she claimed, “I didn’t have much formal study, but I was educated by poets …” Amália understood very well the lyrics she was singing. In addition to her marvellous voice, she had an intelligent way of singing [uma dicção inteligente]’.

In the interview, Mísia goes on to talk about the verses that Amália wrote, singling ‘Lágrima’ out as ‘the fado that made me love fado, my fado fetish’. Mísia recorded an earlier version of the song on an early album, 1993’s Fado, and would return to it for one of her last, 2019’s Pura Vida (Banda Sonora). The 2019 version is one of several tracks on Pura Vida featuring electric guitar, which Mísia said she used to convey ‘the feeling of tragedy’. More forcefully, in her liner notes, she writes ‘the Portuguese guitar is Heaven and the electric guitar Hell’.

On a track such as ‘Ausência’, there is a strong contrast between the two instruments. But on ‘Lágrima’, the electric guitar is the only instrument other than Mísia’s vocal, making for an unusual arrangement. Spanish musician and producer Raül Refree provides the guitar and arrangement on this version. Though unusual, this feels like a more understated version than those Mísia had previously recorded. There is still drama around the longed-for tear, however; when she reaches that word, Refree’s guitar falls silent and the singer’s intake of breath is audible. It’s a subtle moment, suggesting a maturity of approach that is then underlined by a firm resolution of the lyric.

While it’s no more unusual for a fadista to revise a favourite song than it would be for a jazz singer, there’s something in Mísia’s trademark dramatic presentation—in her liner notes and interviews as well as in her performances—that makes this late take on ‘Lágrima’ feel more like a painter obsessively returning to a scene: Paul Cézanne with Mont Sainte-Victoire, for example. Mísia herself makes analogies with painters, writing in the liner notes to Pura Vida:

I do not think Fado is happy or sad, it is Life, Fate. Only a music with this nobility allows us to use its most symbolic melodies the way painters use primary colours to express everything their souls need to say. That is why I say that this album includes Fado musics but it is not an album of Fado.

It’s a slightly confusing message, but perhaps no more so than the ones we always encounter when trying to define fado. Fado, as Amália would sing, is ‘all I know and that I can’t say’.

Running through it all are those objects, gestures and signs of longing, a yearning that is unending. Speaking about her ‘fado fetish’ song, Mísia told Pons, ‘This tear will never stop flowing’.

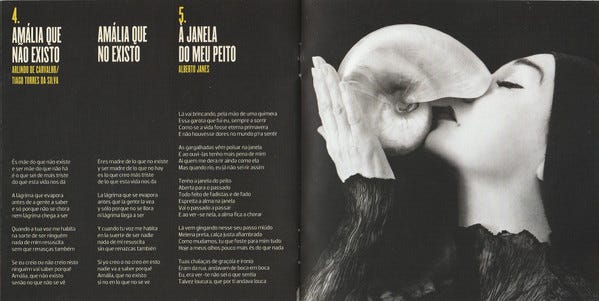

A final tear reference before I pause from remembering Mísia remembering Amália. It comes from a 2015 album, a double CD simply entitled Para Amália. That album doesn’t include ‘Lágrima’, though it has several other songs from the Rodrigues catalogue. It also contains newly composed songs that would fit well in my ongoing series of songs about musicians: ‘Amália Sempre E Agora’, written by Amélia Muge and Mário Pacheco; ‘Amália Que Não Existo’, by Tiago Torres Da Silva; and ‘Madrinha de Nossas Horas’, a new poem by Mário Cláudio, author of ‘Xaile de Silêncio’.

There’s also ‘Uma Lágrima por Engano’, a song with a lyric by Mísia constructed from several song titles and lyrics associated with Amália. Rather than provide a translation for the quoted lyrics below, I’ve linked some of the titles and lyrics to recordings. Aside from being a quick primer on the Amálian repertory for anyone inclined to follow them up, the links at indicate how that repertoire is studded into Mísia’s song.

Nasceu sem ti a cidade Lisboa ficou pequena Nesta Fria Claridade Deito-me cheia de penas Amália nossa Senhora, Luz deste cego caminho, Na tua Prece redentora Erros Meus choro baixinho, Foi por vontade de Deus que de nós foste levada num Barco Negro p’los céus Triste Sina Conta Errada Vagamundo por ti trago O meu coração cigano Roubam-me as cordas do Fado Uma Lágrima por engano!

The ‘Lágrima’ reference at the end should be obvious for anyone whose stayed with me this far, though I’d also note that this ‘fado fetish’ song is also quoted in the first verse (‘cheia de penas’ is the first line of ‘Lágrima’).

What more to say? Only that there’s more than one kind of listing going on here. The obvious one is the accumulation of fragments, the almost verbless set of things common to list songs. When I wrote about Richard Dawson’s ‘Fulfilment Centre’ recently, I mentioned Ian Bogost’s take on Tom Jobim’s ‘Águas de Março’, a song that ‘gives sonorous voice to flat ontology’. Another term Bogost uses is ‘ontography’, a way of writing that tries to capture ‘the jarring staccato of real being’.

When I wrote about the musicality of lists last year, I mentioned that, in addition to ‘list’ meaning a collection of short pieces of information, the word can also refer to leaning. And I said that list songs often have a listing/leaning quality to them, another aspect of Bogost’s ‘jarring staccato’. I suppose we could also think of list songs as ‘lean-to’ songs, constructed from bits and pieces that wouldn’t otherwise go together.

I like the suggestion of asymmetry that comes with this definition of list/ing. While Mísia finds a way to scan her Amálian fragments, there’s a risk of the song leaning into them, collapsing in on itself. For me, this brings to mind a description of fado and saudade written by Rodney Gallop in 1933:

In a word saudade is yearning: yearning for something so indefinite as to be indefinable: an unrestrained indulgence in yearning. It is a blend of German Sehnsucht, French nostalgie, and something else besides. It couples the vague longing of the Celt for the unattainable with a Latin sense of reality which induces realization that it is indeed unattainable, and with the resultant discouragement and resignation. All this is implied in the lilting measures of the fado, in its languid triplets and, as it were, drooping cadences.

I’ve found myself using that ‘drooping cadences’ line often over the years, and not only when talking about fado. Lilting, drooping and listing are not the same, but they all say something about the distribution of weight in a song.

There, for now, is where I’ll stop my tracing of these shifting weights, these rituals and flowing tears, these moonlit shadows and absences, these songs of despair and of bearing up. There is much more that fado is and that I haven’t touched upon, as I’ve been reminded in revisiting the genre for these last two essays. I’ve enjoyed returning to the work of Amália and, perhaps even more, of Mísia. She was an artist whose work I came to know so well while trying to make sense of fado two decades ago, and I’d yet to process the effect on me of her death, though I felt it deeply when I read the news last summer.

‘Matar’ translates literally as ‘to kill’, with ‘morrer’ being used for ‘to die’. For the sense of this song’s final verse, however, I have found ‘how happy I would be to die’ poetically preferable to the more literal ‘how happily I would let myself be killed’ (the translation by Ivan Moody used in the CD booklet of Ritual) or ‘for such bliss I would die’ (Pascale Petit’s translation in the book Saudade: An Anthology of Fado Poetry).

Another absolutely fantastic article written with so much respect and passion. Obrigada.

Fado is new to me, and I have enjoyed this two-part history lesson and your contextual and critical analysis of musicians and songs. I love the analogy of the mourning shawl. The songs, like the shawl, wrap, protect, and provide cover & warmth as well as obscure, hold tight, and shield one's grief.

I went to Portugal in 2003. We were in Lisbon for a few days before my sister and her family arrived, and then we all hired a car and drove down to Faro (or was it Lagos?) on the Algarve. Our kids were young then, so we didn't venture out into bars, but I am sure I may have heard fado in cafes, restaurants, or even on the street. We had a wonderful time in Lisbon, and it was still a bit gritty in 2003; I am sure it has changed a lot since then.

I don't feel that I can comment too deeply on fado itself, but I really appreciate you as my teacher, Richard. Thank you!