The Musicality of Lists Part 1

In which Bob Dylan reads canned food labels, Edwards Lear and Gorey get abecedarian, and Robert Wyatt riffs on Bob Dylan.

As 2023 nears its end, we are well and truly into listing season. While there are many forward-facing or anticipatory lists at this time of the year (Christmas to-do lists, shopping lists, resolutions for the new year), most are retrospective: the Top 100, 50, 25 or 10 movies/books/albums/TVshows/sporting events/stories of the year. I’m always struck by how early they start (many appear in November) and I tend to hold off getting involved until as late as possible. So, while I may end up sharing my own ‘of-the-year’ list(s) here or elsewhere, it’s unlikely to happen until the very end of December or even early January.

In the meantime, I’m going to publish three pieces about lists and, specifically, about how lists sound. I’m labelling these posts ‘the musicality of lists’ and I’ll be focussing on the use of lists in literature and song for the most part. My starting point, however, is a film.

A reciter of food labels

Bob Dylan will be a recurring presence in my posts about the musicality of lists and I want to start with the sound of his speaking rather than singing voice. The audio clip below is taken from Sam Peckinpah’s 1973 Western, Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid. The film’s soundtrack was composed by Dylan, with its most famous song being ‘Knockin’ on Heaven’s Door’. Dylan also appeared in the film, playing a mysterious character named Alias. This excerpt (also available at the time of writing as a film clip on YouTube) is from a scene in a bar, when the Sheriff Pat Garrett (played by James Coburn) orders Alias to read the labels on a shelf of canned food as a way of staying audible but out of the way. Alias starts reading the labels:

The result of this set-up is that we get to hear one of America’s most lauded songwriters—a ‘poet of rock n roll’—reading a list of foodstuffs, mostly beans. There’s humour to the scene, both within the film world in which Alias’s fool-like character plays his part and in the adding of new layers to the enigmatic Dylan persona, providing another thing among countless others that Dylan has been for his fans: a reciter of food labels.

But there’s also a kind of poetry to the scene and, to my ears, a musicality that is at the heart of what I want to talk about here and in the next two posts. I happen to be one of those people who love the sound of Dylan’s voice, and have done since some point in my mid-teens when I got over an earlier aversion to its dominant presence in the family house and the car stereo (my dad’s been a huge Dylan fan since the 1960s). I admire Dylan’s phrasing and the way he emphasises certain sounds by elongating syllables, shifts the stress of words and phrases, adds nasal twangs, raspy grain and occasional, surprisingly tender mellowness, and delivers mostly understated but hilarious dry humour and irony to the lines he sings or speaks.

I enjoy hearing Dylan in interview almost as much as I enjoy hearing him in song; his appearances in two Martin Scorsese documentaries and his side career as a radio host highlight his skill as a wry observer of his own life, a consummate storyteller and an intriguing, if not always reliable, narrator. Listening to him recite the contents of food labels reminds me of what I appreciate in the tone, phrasing and humour of his voice, offering a reminder of how seemingly mundane content can be brought to life by evocative voices and how important listing has been in Dylan’s own songs (I’ll come back to that in a subsequent post).

In thinking about listing here, I’m mainly thinking about how lists of words have a sonority or musicality to them, but I also want to play with another meaning of listing, which is to do with tilting or leaning to one side, causing to become unbalanced. Dylan’s voice connects to this meaning of the word in that his pronunciation makes the lines of his songs tilt or lean, forever threatening to unbalance verses, songs and spoken stories, but then managing, for the most part, to set them right again.

That listing/leaning quality is also, I would argue, part of the musicality of lists (yes, lists have a tendency to list). To start exploring that musicality, I want to think first about how lists sound before moving later to the use of lists in songs. I believe that lists work well in songs because there is already something catchy and songlike about lists themselves.

What lists do

Lists have long been a source of fascination to authors, artists, philosophers, scientists, literary theorists, anthropologists and many more. In the 1970s, the social anthropologist Jack Goody theorised the list as a way for communities not only to take stock of things that they were growing, accumulating and trading, but also as a way of constructing stories that they could tell about themselves and others. Goody thus saw lists as a key moment in the development of literacy.

The artist and journalist Katie Kitamura, meanwhile, starts at the other end of the process by considering listing as a literary device or style rather than a stepping-stone to literacy. ‘How do we describe the fact of human existence?’ Kitamura asks:

At a certain point, perhaps, style fails us. Language, even … at its most evocative, becomes less of an aid and more of a difficulty. In these circumstances, a certain kind of writer has, again and again, reverted to the list – perhaps as the simplest proof of existence in the first place. It's no accident that these lists often delineate material objects, the physical evidence of a life.

This is an aspect of listing that has long fascinated me, and some of my favourite writers have used lists as ways of taking stock of their own and others’ lives, memories and fragile existence. I’m thinking here of writers such as the Argentinian Jorge Luis Borges, who placed listing at the heart of his prose and poetry, and the French authors Roland Barthes and Georges Perec, who wrote short, brilliant texts listing their possessions, their likes and dislikes, and the objects and events that told the stories of their lives. Listed objects could become what Barthes called ‘biographemes’, small elements within a life that managed to evoke or summarise a person in a way that more extended prose sometimes failed to do.

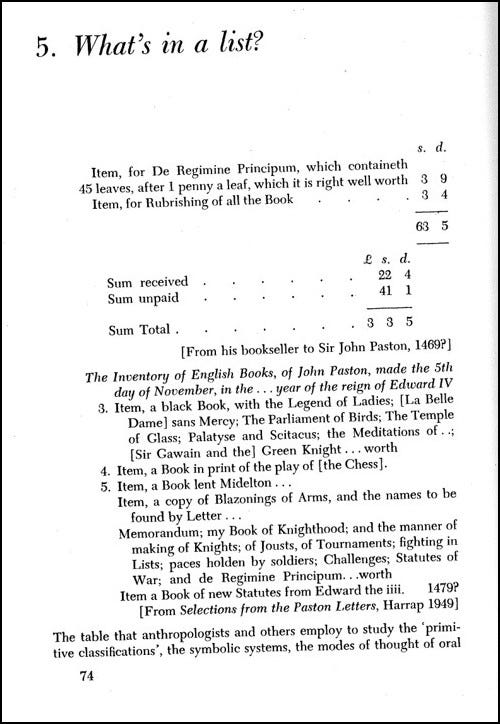

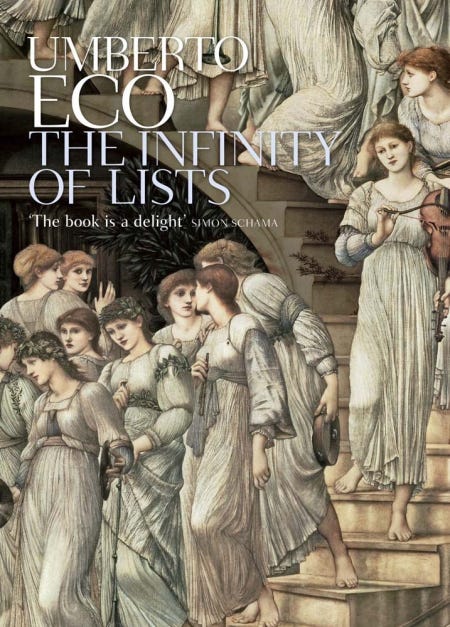

As a student, I was swept up by the listing to be found in Pablo Neruda’s epic poetry (from his ‘Elemental Odes’ to his Canto General), in the work of Walt Whitman, who wrote of containing multitudes, in the magical realism of Gabriel García Márquez and the closely related style that can be found in the work of the Portuguese novelist José Saramago. These writers loved the epic sweep of accumulated imagery, the excessive flow of piled-up verses or pages-long sentences that felt like lists (even when they weren’t) due to a sense of exhaustive completeness and abundance, something that always hinted at what the Italian writer Umberto Eco called ‘the vertigo of lists’ (Vertigine della lista is the Italian title of the book published in English as The Infinity of Lists).

Lists are not always lists of objects, though I suppose those are the ones that interest me most in Songs and Objects. But even lists of events or other things can create an object-like quality because reality gets condensed into items within a list.

Referring to lists of objects in the introduction to his compendium of lists in literature, Francis Spufford makes a comparison between the literary list and the catalogue list, observing that ‘A catalogue of a collection describes its objects so that they can be imagined as nearly as possible in the absence of the objects themselves, for a practical purpose; by doing so it offers them to multiple interpretations, to impractical delight in what goes next to what’. A literary list, meanwhile, represents ‘the stage just before language changes its status by becoming imaginative, ceasing to be a simple denotation for objects and becoming a body in itself with its own self-sufficient rules’. Writing, then, would be the filling-out of imaginative detail, putting wind into the lacklustre sails of merely listed word-objects.

Listing can also be a literary end in itself and not just a means, as Spufford notes, which is why there are so many enjoyable literary lists. To the textual pleasure of lists, I want to add a sonic pleasure. Whereas Jack Goody was keen to stress the ways that lists might have been ways from oral cultures to move towards being literate cultures, with lists working as a kind of outsourcing for information stored in the brain, I’m interested in the ways that lists invite oral recitation. Sound makes things catchy, which is why learning a foreign language or a set of calculations or a historical event is aided by spoken. chanted or sung elements, which often are kinds of lists. Think of mnemonic devices used to recall multiplication tables, or how many days there are in each month.

Lists, in fact, are all about sound, rhythm and repetition. Find a good written list in a work of fiction or factual reporting and read it, noting the affect created though rhythm, imagery, alliteration, and so on. Read it silently and aloud: there should be notable effects either way, though they may be quite different. This is the power of the word in its sonic dimensions, as words themselves become sound objects.

The sound of lists may or may not summon up what the word is referring to. Conisder the following for example, which I’ve taken from Mario Maffi’s New York City: An Outsider’s Inside View:

In certain subway stations ... a rolling rumble that almost induces feelings of panic as the trains draw near ... honkings, sirens, skiddings, and brakings [of] the traffic ... hurried scurrying along the massive sidewalk stones, the wooden thud of skateboards leaping up steps, the intermittent whirring of helicopter blades, the metallic frizzle of police car radios, the full-throated singing of a passerby ... the vibration of the air as it sneaks its way about the stairways of the high-rises ... the wind that whistles through cracks in the guillotine windows; the deep droning of the air-conditioning system of the supermarket below the house; the sound of a phrase muttered in the narrow streets that echoes all the way up to the top floor ...

When I read this list, I can tell I’m supposed to be imagining the sounds that Maffi describes. But there is also the incantatory power of the list, which builds a different but complementary affect that still has me thinking of sound, rhythm, musicality, and in which I may be focussing on these features of the list itself rather than what each item of the list describes. This complementary effect still gets at what Maffi is writing about because I am still thinking about sound: the cacophonic and multiphonic sonic palimpsest that is New York city in my imagination.

The sound of nonsense

In 2018 I published a book called The Sound of Nonsense, in which I connected nonsense literature of the kind written by Lewis Carroll, Edward Lear and Edward Gorey to examples of sound poetry and popular song. In thinking about nonsense literature, I wanted to emphasise the way it sounded. Rhyme and rhythm, which Jacqueline Flescher recognises as ‘the very stuff of nonsense’, are vital aspects of nonsense songs and limericks and provide examples of the sonic logic that provides the framework to the nonsense.

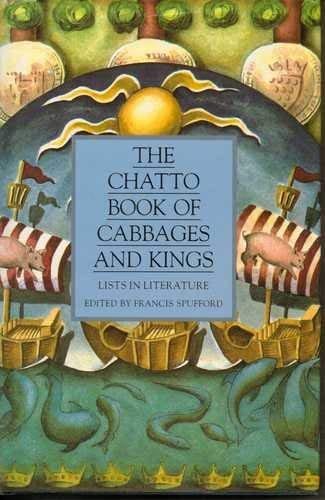

Alliteration, which is a particular kind of rhyming-rhythmic device, plays an important role in the way sound orders words in the nonsense text, as in the lines from Lewis Carroll’s ‘The Walrus and the Carpenter’ that tell ‘of shoes and ships and sealing-wax / Of cabbages and kings’. As Flescher notes, ‘Once the pattern has been so sharply defined, shoes, ships, and sealing-wax can co-exist happily, and cabbages and kings live side by side’. A kind of normality thus ensues, returning us from the world of nonsense. Francis Spufford, who uses this same example for the title of his compendium of lists, writes that these ‘five words from different categories of concrete noun … alliterate as if they sat together by natural dispensation of sound’.

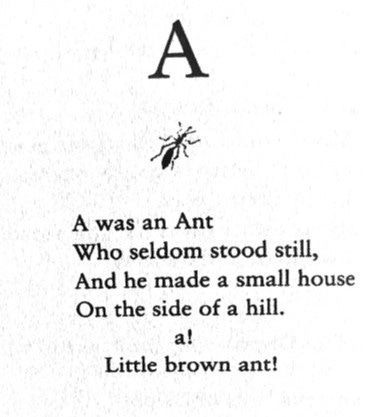

Another way in which alliteration, rhyming and listing combine is in the nonsense alphabet, of which Lear provided examples such as ‘A was an ant’, ‘The Absolutely Abstemious Ass’, ‘A was an Area Arch’ and ‘A was once an apple pie’. In the latter, each verse begins with the same verbal and rhythmic structure—‘A was once an apple-pie’, ‘B was once a little bear’, ‘C was once a little cake’—deviating only when encountering a letter with more than one syllable or whose word provides difficulties for the single syllable word or the countable noun: ‘W was once a whale’, ‘X was once a great king Xerxes’, ‘Z was once a piece of zinc’.

Variations applied to the opening lines cater for the need for real words to be used, whereas the body of the verses show allegiance not to existing vocabulary but to the sonic pleasures of nonsensical rhyming groups that riff on each alphabetical noun: ‘apple-pie’ morphs into ‘Pidy / Widy / Tidy / Pidy / /Nice insidy’; ‘cake’ into ‘Caky / Baky / Maky / Caky / Taky Caky’; ‘goose’ into ‘Goosy / Moosy / Boosy / Goosey / Waddly-woosy’.

Like Lear, Edward Gorey was drawn to writing and illustrating nonsense alphabets that play with the possibilities of sonic serialism. The Gashlycrumb Tinies (1963) details, in abecedarian form, the grisly undoing of twenty-six children, from ‘Amy who fell down the stairs’ and ‘Basil assaulted by bears’ to ‘Yorick whose head was knocked in’ and ‘Zillah who drank too much gin’. The Utter Zoo, published in 1967, is an A-Z nonsense bestiary that houses the Ampoo, the Boggerslosh, the Ippagoggy, the Twibbit, on through to the Zote. In the former work, sound plays its most obvious form in the rhyming dactyls; in the latter, there is the pleasure of speaking the beast’s names out loud.

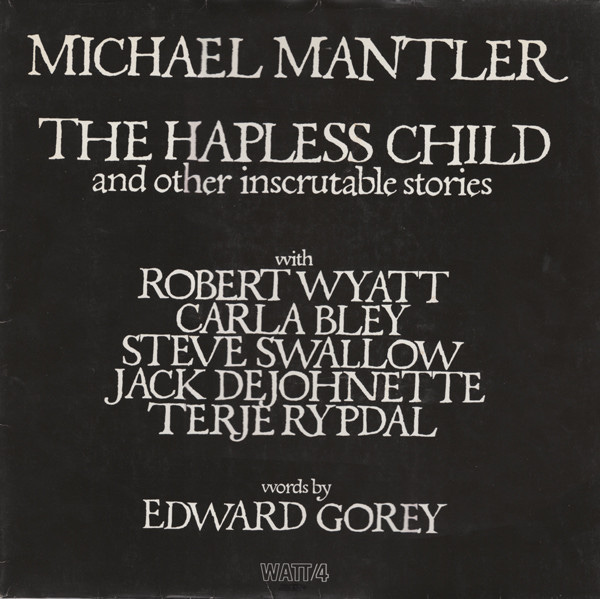

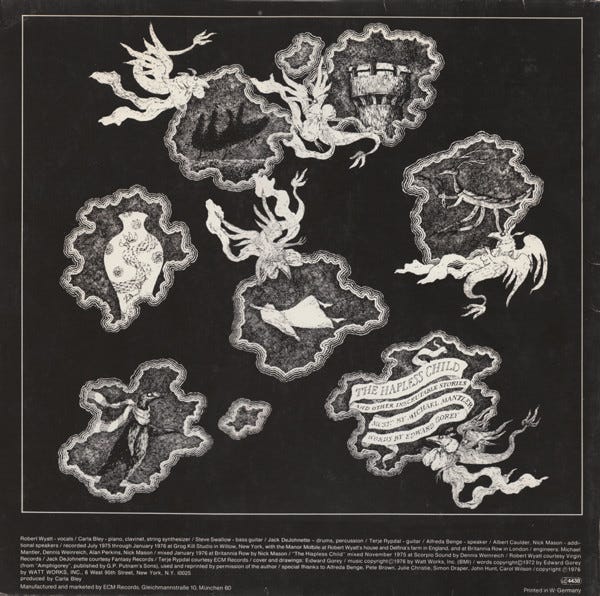

As a link to the next post, where I’ll be focussing on lists in popular songs of more recent vintage, I’ll mention the work of Robert Wyatt, a musician who has a long association with the British and American nonsense traditions. As well as many references to the work of Carroll and Lear that can be found in Wyatt’s songs, he also collaborated with the arranger Michael Mantler on an adaptation of Edward Gorey’s work in 1976.

Wyatt has deployed the rhyme and rhythm of the alphabet in songs such as ‘A Concise British Alphabet’, recorded with his group Soft Machine. And he has shown a fascination with the rhythmic and sonic qualities of lists in songs like ‘Blues in Bob Minor’.

Like ‘Weird Al’ Yankovic’s ‘Bob’—a parody of Bob Dylan’s songwriting that uses a list of acronyms to emulate list-like Dylan songs such as ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues’—’Blues in Bob Minor' doesn’t appear to be based on a single song, though it certainly borrows from ‘Subterranean Homesick Blues’ with lines such as ‘Toe’s in the water but you've only got ten' and ‘Don’t take a weathergirl to see where the wind is blowing’. Like Yankovic, Wyatt provides his own lyrics, in this case a relentless stream of word associations. As he sings ‘Tunnelling a wormhole Eartha Kitty catfish’ and ‘Hibernate in winter of our discotheque no end in sight’, the words and phrases combine to suggest others: whole earth, Kit Kat, winter of our discontent, techno, insight …

As I mention in my section on Wyatt in The Sound of Nonsense, the effect of the listed word associations is similar to what Marnie Parsons says about the modernist poet Louis Zukofsky in Touch Monkeys, her book about ‘nonsense strategies’ in poetry. Parsons notes how Zukofsky juxtaposes words that are ‘seemingly incongruous’ but which send out ‘sonal shoots’ that ‘anticipate words that aren't there’. I like that term ‘sonal shoots’ and I think it relates to what I was trying to describe in my book as ‘the nonsense moment’, that is ‘the moment in perception when one is beyond, between or ahead of the moment of ascertaining sense … a glitch moment, a temporary period of blurring, the point in the process of code-switching where the codes are muddled’.

Wyatt's ‘Blues in Bob Minor’ has another effect. In addition to its own internal soundplay, it makes ‘sonal’ reference to the work of Bob Dylan and therefore acts as a critical reading of Dylan's own linguistic and sonic experimentation.

Mention of Dylan brings me back to the starting point of this post. There will be more Dylan in the next posts as I turn to the use of lists and listing in various songs.

The text above is a slightly revised extract from the fourth episode of the Songs and Objects podcast, originally released in November 2021. I’ve divided the episode into three for this version. Parts 2 and 3 will follow soon.

Enjoyed this very much — have never thought much about lists per se at all, and this was a wonderful introduction to them as worthy of literary/musical attention.