This is the third part of my reflections on Richard Dawson’s object-oriented songcraft, following ‘I Can Feel It in My Molecules’ and ‘The Quiltmaker’.

The songs featured in this post use the device of listing everyday objects in ways that highlight their humanising and dehumanising effects, switching between the ‘flat ontologies’ described by theorists of object-oriented ontology (OOO) and the ‘evocative objects’ and ‘object biographies’ analysed by sociologists, anthropologists and media theorists.

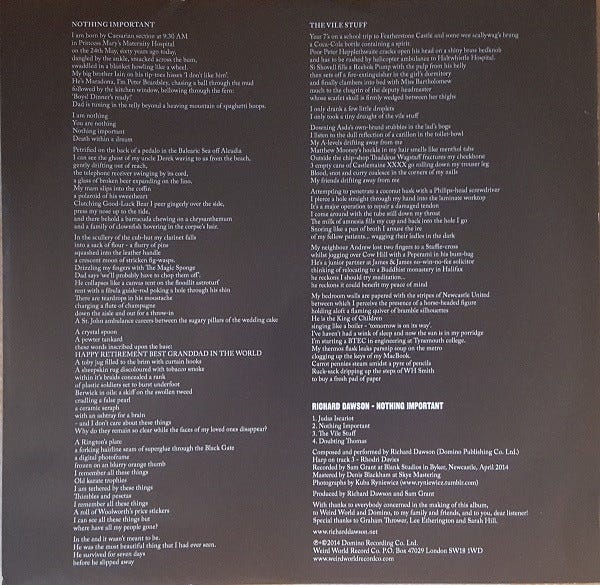

Tethered by Things: ‘Nothing Important’ (2014)

‘Nothing Important’ is a sixteen-minute song that folds together several narratives over five long verses, a refrain and a short final verse. The lyrics are written in first person and relate the remembered fragments of a life, focussing on members of the narrator’s family. Because there are references to Newcastle upon Tyne and the North East—the Princess Mary Maternity Hospital, Ringtons tea company, the Black Gate of the city castle, Berwick-upon-Tweed—and because Dawson has discussed the song by recollecting scenes from his past that inspired it, there’s a temptation to read the song as autobiography. It’s important to note, however, that Dawson has also mentioned the fallacy of his own memories when discussing the song:

Some things get exaggerated in the same way that a little scratch on your hand can develop into a really nasty wound if you don’t leave it alone but it all comes from the same place. I hope there are little clues about where those moments are … It could be one person or a number of people. I think there are a number of possibilities about who the singer is and whether it’s one person or two or many is open for debate. Whether they are many who think they are one, or one who thinks it is many, or whether it is even human to begin with is a moot point.

—Richard Dawson, interview with John Doran for the Quietus

I’m tempted to read the title track of Nothing Important and its long companion piece ‘The Vile Stuff’ not so much as personal autobiography, but something closer to collective or regional autobiography. By ‘regional autobiography’ I mean something to do with those regional references thar appear in many of Dawson’s songs. Again, we shouldn’t take them too literally; there’s that point that Dawson makes about everyone having a Newton-by-the-Sea, that these specific reference points can be translated by listeners into their own local versions. But it still seems important to me that its these details rather than those that illustrate the songs.

Another way to explain what I mean is to think about three versions of what I call the ‘I remember’ template. By this I mean Joe Brainard’s 1975 book I Remember, consisting of a series of entries beginning with the words ‘I remember’ in which Brainard recollects moments from his past, some of them highly individual and others doubtless shared by an enormous number of his contemporaries. The second version of the template I’m thinking of is Georges Perec’s Je me souviens (1978), not a direct translation of Brainard’s text into the French language (which was done by Marie Chaix), but rather an adaptation of the template that would incorporate Perec’s own memories and a set of French cultural reference points. The same thing was done by Gilbert Adair in 1986 for his book Myths & Memories; Adair adapted the template Perec had inherited from Brainard, using references that would speak more obviously to a British readership.1

When I think of the Ringtons plate that features in ‘Nothing Important’, I sometimes think of the ‘England’s Glory’ matchbox that adorns the cover of Adair’s book.

What all of these writers achieve is a rendering of personally-inflected regional memory, the kind of things that reinforce what Benedict Anderson called ‘imagined community’.

Two of the verses of ‘Nothing Important’ rely on extensive listing, presenting the contents of a room (or rooms) that serve as witnesses to lives lived. The first of these verses is closer to being a neutral list, if indeed lists are ever really neutral:

A crystal spoon A pewter tankard These words inscribed upon the base: "HAPPY RETIREMENT BEST GRANDDAD IN THE WORLD" A Toby jug filled to the brim with curtain hooks A sheepskin rug discoloured with tobacco smoke Within its braids concealed a rank Of plastic soldiers set to burst underfoot Berwick in oils: a skiff on the swollen tweed Cradling a false pearl A ceramic seraph With an ashtray for a brain - and I don't care about these things Why do they remain so clear while the faces of my loved ones disappear?

As the list goes on, evocative objects are lined up in a manner similar to the earlier ‘Wooden Bag’. Like Brainard, Perec and Adair, Dawson’s narrator is explicit about remembering—‘I remember all these things’ (repeated), ‘I can see all these things’—but also claims that the things themselves are unimportant and even obtrusive in that they stubbornly persist while the people the singer wishes to remember disappear from memory: ‘Where have all my people gone?’

There is poetry in all this stuff, and in the listing of it, suggesting that art always goes further than the flatness or equivalence of objects that its philosophical counterpart might seek to highlight (I’m thinking here of philosophers of object-oriented ontology—I’ll come back to them shortly). Poems and lyrics do this through poetic language, while song does it through adding musical expression to poetic language, forging a new poetic language of its own.

The more interesting tension to note here might not be between poem and song but between prose and song. Michael Hann, reviewing Nothing Important for The Guardian in 2014, described the two long songs on Nothing Important as ‘matter-of-fact diary entries rather than verse-chorus-verse songs’. I’d contend that they work equally well as poems, and the lyrics that appear in the LP’s inner sleeve add weight to this.

We are given a seemingly random assortment of objects and yet we can understand from the context that this is in fact a quite precise collection, a catalogue of what might be found in many people’s houses, rooms or tables. As well as Brainard and Perec, I think of Jorge Luis Borges and his frequent revisiting of the theme of who will be remembered and how. In a passage from ‘The Witness’ that I’ve been drawn to quote many times before, Borges moves from the final memories of an imagined Saxon to a reflection on his own mortality:

He is awakened by the bells tolling the Angelus. In the kingdoms of England the ringing of bells is now one of the customs of the evening, but this man, as a child, has seen the face of Woden, the divine horror and exultation, the crude wooden idol hung with Roman coins and heavy clothing, the sacrificing of horses, dogs and prisoners. Before dawn he will die and with him will die, and never return, the last immediate images of these pagan rites; the world will be a little poorer when this Saxon has died.

Deeds which populate the dimensions of space and which reach their end when someone dies may cause us wonderment, but one thing, or an infinite number of things, dies in every final agony, unless there is a universal memory as the theosophists have conjectured. In time there was a day that extinguished the last eyes to see Christ; the battle of Junín and the love of Helen died with the death of a man. What will die with me when I die, what pathetic or fragile form will the world lose? The voice of Macedonio Fernández, the image of a red horse in the vacant lot at Serrano and Charcas, a bar of sulphur in the drawer of a mahogany desk?

Such things are matter that matters, even when we believe that what matters most are the people the objects point towards.

I particularly like the Borges passage in this context, given that Dawson is an artist whose frame of reference is just as likely as Borges’ to span centuries.

Many of the references in ‘Nothing Important’ are to places and things which have either disappeared or have a precarious existence in the twenty-first century. The Princess Mary Maternity Hospital in Jesmond was closed in 1993. Woolworth’s is long gone from British high streets. The classic era of Maradona and Beardsley on the football pitches of the world is pre-millennial.

As for Ringtons, I’m drinking a cup of their tea as I write this, just as I do almost every morning. I buy the tea from a man who delivers it to my door, with a van and a basket just like Ringtons have been doing for decades. As far as I can tell, the company continues to be successful, but it still feels like the kind of tradition that struggles to sustain itself in this world.

Endless Things: ‘Fulfilment Centre’ (2019)

‘Fulfilment Centre’ relates the experiences of workers slogging to meet orders in a warehouse, with the work depicted as relentless and dehumanising. While the song is structured around people, events and feelings of frustration, it also uses the device of verbless listing as a way of underlining the endlessness of the ‘tat’ contained in the centre and of the labour required to process it.

Trying to keep up with the nonstop demand for ‘trainers and tarot cards, dash-cams and wall-art, Lego and shaving foam, onesies and retractable extension leads’, the pickers are doomed to Sisyphean repetition.

‘Fulfilment Centre’ sends the message that desire can never be fulfilled, even as the objects listed in the song fulfil some part of their destiny as they move from the flat, alien world of items living incongruously together to a new life elsewhere. This song, like ‘Nothing Important’ and ‘Wooden Bag’, shares qualities with a subcategory of songs known as list or catalogue songs; examples include ‘These Foolish Things’, ‘Thanks for the Memory’ and ‘It Never Entered My Mind’. Such songs do explicitly what I suggest many other songs do partially, which is to place objects in play with each other.2

In his book Alien Phenomenology, or What It’s Like to Be a Thing, Ian Bogost suggests that lists found in literary texts produce what he and Graham Harman refer to as ontography, a way of representing ‘the rich variety of being’. For Bogost and Harman, ‘the inherent partition of things is a premise of OOO [object-oriented ontology], and lists help underscore those separations, turning the flowing legato of a literary account into the jarring staccato of real being’.

Bogost extends this to examples in songs, claiming that Tom Jobim’s ‘Águas de Março’ ‘gives sonorous voice to flat ontology’. While OOO theorists look to the listing of things as evidence of a world of objects not reliant on humans, others see listing as an inherently human reference.3 Katie Kitamura discusses the list as ‘proof of existence’, something that bears witness to a life: ‘Lists are used as a formally alienating device, a dehumanizing agent, that is nonetheless entirely wrapped up in human life’. I’ve written about that kind of thing in more detail in my three-part series on the musicality of lists.

‘Nothing Important’ and ‘Fulfilment Centre’ cover both these axes, albeit in different directions. Where the first song strains to see past the listed objects to the human lives they witnessed, it leaves little doubt that these objects can still summon up ghosts (and that sometimes ghosts are all that can be summoned). The second song uses the alienating device of listing commodities to emphasise dehumanizing work conditions, but reminds us that these objects bear witness to lives outside the workplace; whether they have the potential to be anyone’s future evocative objects is open to debate, but the possibility cannot be ruled out.

Futile Things: ‘Museum’ (2022)

‘Museum’, from the 2022 album The Ruby Cord, is one of Dawson’s sweetest, most accessible melodies; if you only have time to check out one of the musical examples linked to in this post, I’d recommend this one.

That melody, and some of the words, were first essayed on a couple of the many albums released by Richard Dawson and Sally Pilkington as part of their Bulbils project. The refrain can be found as the title track of Bulbils 17: Distant Memories; it also appears in elongated form on Bulbils 35: Vision.

In keeping with other songs on The Ruby Cord, ‘Museum’ employs science fiction ideas, presenting a welcome message to the first visitor to ‘our museum / in the dozen centuries / since humans disappeared’. It’s not clear who is speaking, who ‘we’ are, but presumably a more-than-human entity: alien, animal, AI?.

Nor am I sure who the ‘you’ of the song is: ‘distant memories of you’. A human survivor? Or just a saudade-fuelled robot making the metaphorical leap from the memories that a museum puts up on trial to their own time-and-spaced removal from an object of affection as they put in the hours on this endless caretaker gig?

The contents of the museum are described harshly: ‘An archive of futility / Miles of hard corridor / Bustling with projected people / Bound in loops of light forevermore’. Not so distant, perhaps, from some of the museums that already exist back on our human world here and now, and even imagined decades ago: projected loops of light sounds a bit like a 1970s sci-fi vision, something George Lucas would have fun with.

Then comes the list, the reason I’m including this song with the others in this post:

Scared young soldiers wielding guns Shoppers idly flicking through clothes Gently spinning astronauts A classroom deep in thought Throngs of cheering football fans A doctor crying alone Riot police beating climate protestors Babies being born

Miles of hard corridor. An archive of futility. When I first heard ‘Museum’, in late 2022, I hadn’t yet read Liu Cixin’s mind-blowing Remembrance of Earth’s Past trilogy. I would read it the following year and, on nearing the end of the final volume, Death’s End, would discover the Earth Civilization Museum, a massive repository built into the body of Pluto to house the cultural treasures and history of a doomed humanity.

Pluto, like Earth, is on course to be flattened, ‘two-dimensionalized’, when two of the book’s characters, Cheng Xin and AA, visit the museum to transport some of the artefacts away from the planet for redistribution in a different part of space. In conversation with the museum’s curator, Luo Ji, they find that the museum has become something more sinister than originally intended: ‘Why, do you still think this is a museum? No, no one visits here. This is not a place for visitors. All of this is but a tombstone—humankind’s tombstone’.

Cheng Xin and AA encounter their own sense of futility as they hear from Luo Ji about the difficulties of preserving any record of human existence for the hundreds of thousands of years that will likely pass before a future civilisation can discover them. What’s more, it seems that little that has been made by humans will compete with the display that the flattened solar system would offer.

Optimistically, the flattened Solar System would not have visitors until a few hundred thousand years from now. In their eyes, Neanderthals and modern humans would appear to be the same species. Cheng Xin looked around at the other artifacts, and none excited her. For themselves in the present, nothing here mattered as much as the world that was dying outside.

They took a last look at the dim hall and left with the artifacts. Mona Lisa watched them leave, smiling sinisterly and eerily.

Two different visions of what a museum of vanished humankind might offer, how it might operate, both connected by the idea that, amidst all the futility and self-destruction, a desire for recovering the past might live on as ‘distant memories’ or the ‘remembrance of Earth’s past’.

Seasonal Things: ‘Boxing Day Sales’ (2024)

To bring things up to date, my final example for this post is Richard Dawson’s most recent single, ‘Boxing Day Sales’. It’s the second of two songs released so far in 2024 in advance of an album arriving next February. Dawson announced it via social media in late November as a ‘bid for the Christmas No. 1’. With his characteristic self-deprecating wit, he posted a longer description to various platforms on the day of release (the below is taken from Instagram):

I wanted to make a small, pure, jaded ‘pop!’ song that would somehow resemble an unwanted Xmas pressie: A pair of novelty socks, some Lynx Africa, or a daft plastic puzzle you find in your stocking then chuck in a drawer for the next 10 years. I hope, despite there not being much room in the verses for the central character to say what’s been troubling them, that somehow their bright spirit might melt away the brown-grey slush, and their voice be heard.

That lumping of the song with a list of unwanted presents marks it as no better than the things it seems to otherwise be critiquing: a seasonal consumerism based on the accumulation of things rather than a dedication to human connection. That critique finds its place in the song’s verses by a list that fits in well with Dawson’s previous songs:

A drawing tablet with a 30 inch screen A hulking stainless-steel espresso machine Green amber earrings, noise cancelling headphones Cranes paused mid-flight on a quilted kimono You can't afford to not own this

This list feels like those in ‘Fulfilment Centre’, with the objects underlined as ‘must have’ lifestyle accessories imbued with a sadness quite distinct from the pewter tankards, Toby Jugs, Ringtons plates, seraph ashtrays, sea shells and handkerchiefs of ‘Wooden Bag’ and ‘Nothing Important’. To paraphrase a classic fado song, all of this stuff exists, all of it is sad, and all of it is indicative of what these songs are all about.

As icing for this seasonal cake, Dawson and collaborator James Hankins have produces a video for ‘Boxing Day Sales’ that turns Richard himself into an object.

Tying Things Up / Doing Justice to People and Objects

‘Can it be that talking about things involves exhibiting the bits and pieces of self that adhere to their substance? Is it possible to do otherwise, or are we hopelessly entangled with things?’ Questions posed by Roger-Pol Droit in his book How Are Things? A Philosophical Experiment (2005).

Questions such as these arise frequently as I work on Songs and Objects. Some of the writers whose work I cite have tried to move away from the attachment of humans to things as a way of challenging anthropomorphism (thinking about objects as being like humans: having ‘biographies’, for example) or a more general anthropocentrism (thinking about things only inasmuch as they mean something for humans). For now, I will note Droit’s discovery that, in seeking to set out a non-personal account of things, he finds himself writing the kind of memoir or intimate journal that he normally ‘detests’.

Meanwhile, discussing his book Paraphernalia: The Curious Life of Magical Things (Connor 2011), Steven Connor observes that

The writing about an object can highlight the “objectness” of one’s own writing … and I think one of the most liberating things about writing about objects is that you stop thinking about the writing. You start thinking about the object. You start thinking, “no, that’s not quite right for the sound of Sellotape. Does it rip, no it sort of rasps but it does a sort of shriek”. So you have to do justice to the object and you stop thinking about the writing.

This resonates with comments that Richard Dawson has made regarding his songwriting, whether it be in the attention given to the description of the objects he uses as devices (the feel of the Ladbrokes pen, the sound of the foil on a strip of pills, the smell of the sea in a handkerchief) or the commitment he feels to doing right by the people he is singing about and for.

This sense of responsibility goes together with an ambition to stretch conventional forms. He has said that ‘you’re not doing justice to the form, but also not doing justice to the community that you’re a part of, if you’re just singing about yourself—well, it has to be something grander. The idea that you would want to make something bog-standard or average, I don’t get that. Let’s be ambitious, even if it really fails’.

The results of this human-oriented songcraft rely, I suggest, on a process of enstrangement whereby the automatization of everyday life is challenged by songs that rely on objects that don’t usually get sung about. The result is that human-oriented narratives rely on object-oriented devices.

What I’ve said about Richard Dawson’s songs in my last three posts could be said of other songwriters. Enstrangement (which I’ll go into in more detail in a future post) could be thought of as a technique used in all songwriting as both a poetic and musical device and as a way of creating new work in familiar templates: in short, as a way of overcoming standardisation.

Similarly, object-oriented songcraft can be found in the lyrical and compositional techniques used by many songwriters. If I single out Richard Dawson for an exploration of these techniques, it’s because I believe that he’s a relatively extreme example. Certainly, he is one of the songwriters who opened my ears to the idea of song objects. I maintain that ‘Wooden Bag’ is, in a very literal sense, an object lesson in how evocative objects do their work, while ‘Joe the Quilt-Maker’ teaches its listeners that quilting points are the elements that fix the patchwork of experience narrated or collaged in songs; they pin things down enough for them to take on recognisable form and stability.

That Dawson articulates the care with which such songs were brought to fruition exemplifies the continued relationship a songwriter has with their craft and its outcome(s). Yet he has also made clear the importance of recognising what is ‘coming through’ in the writing process and of ‘do[ing] justice to what the song wants’.

This opening up of a potential tension can be taken further by a listener who is attuned to what comes to life or notice in song, and what lives on in song itineraries. Such a listener places emphasis on the ontology and agency of objects stacked or stitched together in verses and given vital and viral energy by the weirdly catchy nature of song objects.

I have referred to these books a few times before on Songs and Objects, for example in a post a year ago about Mary Chapin Carpenter’s songs—another three-part series that focussed on memory, objects and listing. I also wrote about Brainard, Perec and Adair more than a decade ago on my Place of Longing blog; these writers, and these works, have been a reference point for me for a long time now.

Part of this description of ‘Fulfilment Centre’ appears as my contribution to

’s recent collaborative post on protest songs. It’s well worth checking out the longer list, and the wider series.I realise some additional information about OOO would be useful here for the uninitiated. As it is, the post is already long and I’m not sure I have space to do justice to the theoretical framework(s). Good places to start are Graham Harman’s Object-Oriented Ontology: A New Theory of Everything (2018), Timothy Morton’s Being Ecological (2018) and Bogost’s aforementioned Alien Phenomenology.

Nice piece. Your mention of “ The Waters of March “ was timely I am off to listen to it again.

Wow, Richard, I am in awe of your passion, research, and level of detail you have given these three pieces! They are extraordinary. I am also somewhat overwhelmed and wish I could offer more, but I don't know Dawson's music/art, and I'm unsure where to start. I did, however, love the quilting analogy in Part II, and coincidentally, when you posted it, I was looking at Pacita Abad's large quilt tapestry pieces!

You have definitely inspired me to explore and listen deeper to Dawson's music. However, I wonder if his work is so quintessentially English, like, say, Michael Head (who I love, btw!) that his lyrical references are missed on many listeners outside of the UK. That said, I did live in England (albeit London) for 14 years, and my wife is English. However, as Dawson is a Northerner, there still may be things lost on my ears and even my wife's (she grew up in Cambridge and London).

Nevertheless, I respect and applaud you for the deepest of dives you have taken us on. I also hope you have shared this three-part essay with Dawson. He would no doubt be chuffed to read it. Thank you for sharing it with us.