While writing about Portuguese music nearly two decades ago, I became fascinated by the number of old records I’d see in the UK that featured versions of songs derived from fados. The two most common were ‘April in Portugal’ and ‘Lisboa Antiga’ (sometimes rendered as ‘In Old Lisbon’). I told the story of the former song in my last post, and it will make further appearances below. I may write about ‘Lisboa Antiga’ later. But I also want to venture beyond the southwest of Europe in this essay to explore the wider world of holiday or souvenir records, a subgenre of easy listening, light or mood music that flourished in the 1960s, though with a longer and still ongoing history.

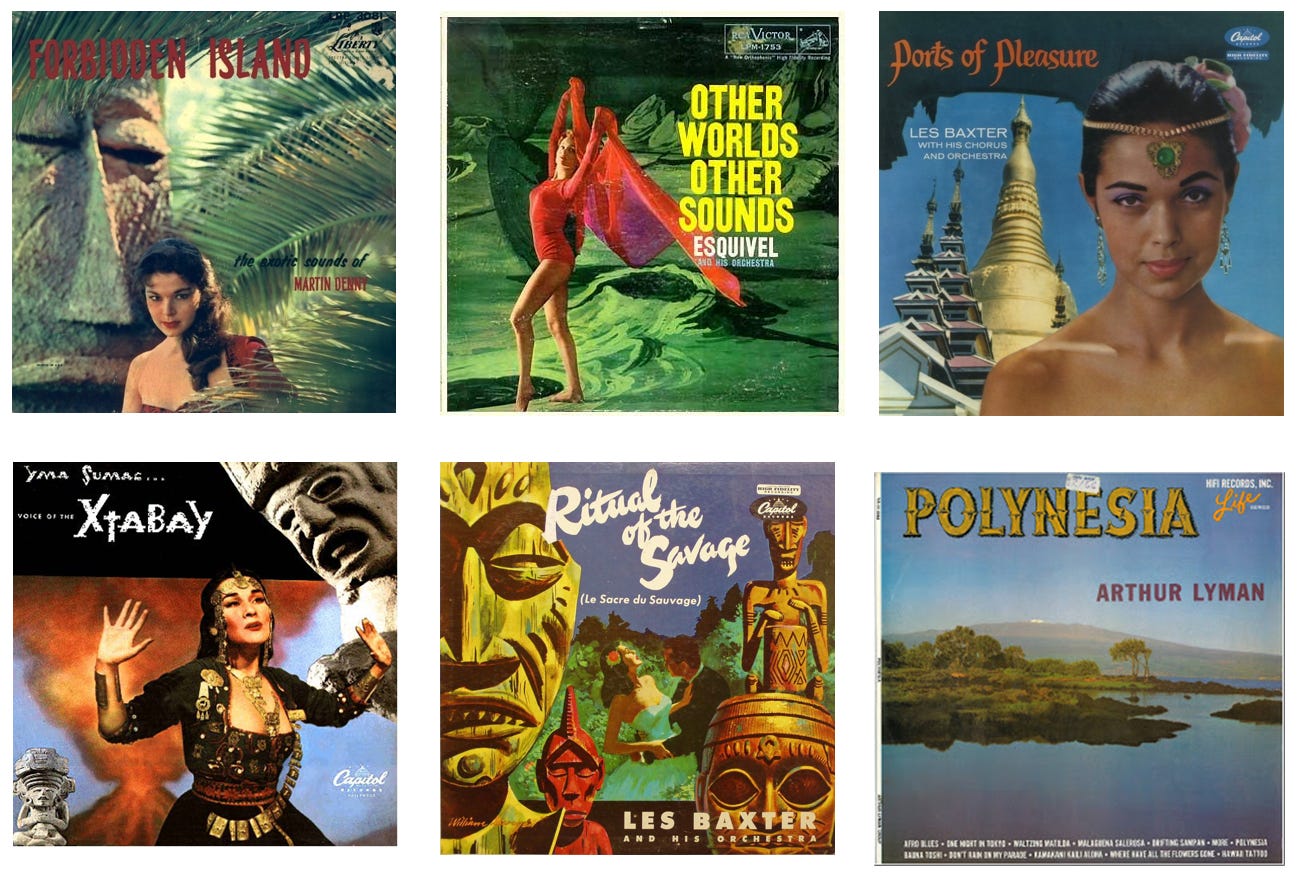

The records I’m writing about here are the kind of thing I used to find a lot when scouring British charity shops. They have something in common with the exotica records of musicians such as Les Baxter, Martin Denny, Yma Sumac and Arthur Lyman, though they’re far less likely to be collected, revered or seen as cool or culturally redeemable. Some have a kitsch appeal, but many lack even that.

There were, I think, a few things that drew me to these records. One was the promise (seldom fulfilled by the music unfortunately) that these records could successfully evoke a sense of place, whether that was an imagined or remembered location. That was also something I’d found interesting in the far more successful evocations of fado recordings, and it was that connection to a country and city so close to my heart that had got me intrigued by these records in the first place.

Another reason was a long-held fascination with music of other countries. While it was obvious for anyone with a modicum of phonographic literacy that these would not be authentic field recordings, traditional tunes or ‘world music’, there was still something alluring to me about records that promised to expose me to the sounds and experiences of other countries.

That exotica connection also played a part. I recall stumbling across Arthur Lyman’s Taboo Vol. 2 in the mid 1990s and wondering what on earth (or elsewhere) it was. Drawn by its lurid cover and promise of ‘exotic sounds’, I bought the LP, took it home and got my first proper introduction to exotica. Around the same time, various labels were issuing compilations of this kind of music as part of a broader lounge/tiki/exotica revival. I didn’t really get the American cultural context of tiki culture or its ironic revivals, but I was intrigued enough to follow up on the music of Martin Denny, Yma Sumac and other exotica artists.

One thing I found interesting about exotica and holiday records is that the LPs were essentially concept albums, mostly predating those rock albums that usually get written up as being the first of their kind. The concepts behind the albums were established not only through thematic connections between the songs, but also through the vital role of the record covers and liner notes.

While I tended to buy exotica records for the total package—music, covers, liner notes, labels—I started buying cheap examples of holiday records in my local charity shops mostly for the covers and liner notes. This is because the music on them was typically not my cup of tea (or glass of Liebfraumilch). It was mostly generic easy listening music played by orchestras, all swooping strings and deracinated arrangements.

In the early 2000s, I started scanning the sleeves of the records I’d collected and posted them on a blog, usually without further commentary. I called it ‘Vinyl Vacations’. I had plans to build a research project from it, but I took other directions with my research and teaching and abandoned the blog to work on other things. The most I’ve done with the material since then is to write about some of it in the occasional journal article or book chapter and to use the records as examples in a university class I ran for several years called ‘Global Pop’.

I’ve enjoyed following the work of other people with an interest in this area of pop memorabilia. In recent years that has included a series of books published by Janet Borgerson and Jonathan Schroeder: Designed for Hi-Fi Living: The Vinyl LP in Midcentury America (2017); Designed for Dancing: How Midcentury Records Taught America to Dance (2021); and Designed for Success: Better Living and Self-Improvement with Midcentury Instructional Records (2024). These books analyse album covers and liner notes as examples of how the LP format taught consumers about things like home entertainment, interior design, travel, dance, leisure and all kinds of other activities.

As the authors put it in Designed for Hi-Fi Living,

midcentury record albums played the role of advice column, cultural guide, and travel brochure, as they promoted postwar consumer lifestyles and celebrated iconic sites, sounds, and tastes of featured locations. And travelers, whether actual or armchair, were offered a comforting position from which they might enjoy a sense of belonging, rather than exclusion, in otherwise unfamiliar places and spaces.

I agree with Borgerson and Schroeder that many covers were designed to teach sophistication and cultural awareness. At the same time, many of my examples I collected in the UK have covers that are not design classics, nor models of sophistication. There is an abject quality to some of them, a point I’ll return to later.

Like Borgerson and Schroeder, most of my examples are mid-century ones dating from the 1950s and 1960s, though I’ve also explored how the holiday record legacy has evolved in the digital era. In my classes, I typically include sessions on how YouTube and Spotify playlists continue ideas and tropes that can be found in much earlier analogue recordings and broadcast media.

While most of the records I’ve considered feature instrumental numbers, I’ll start this tour in more familiar waters, with well-known singers who got caught up in the jet setting holiday fever of the 1950s and 1960s. Given that many of the instrumental albums featured well-known songs shorn of their lyrics, it makes sense to start with some examples that still contain words.

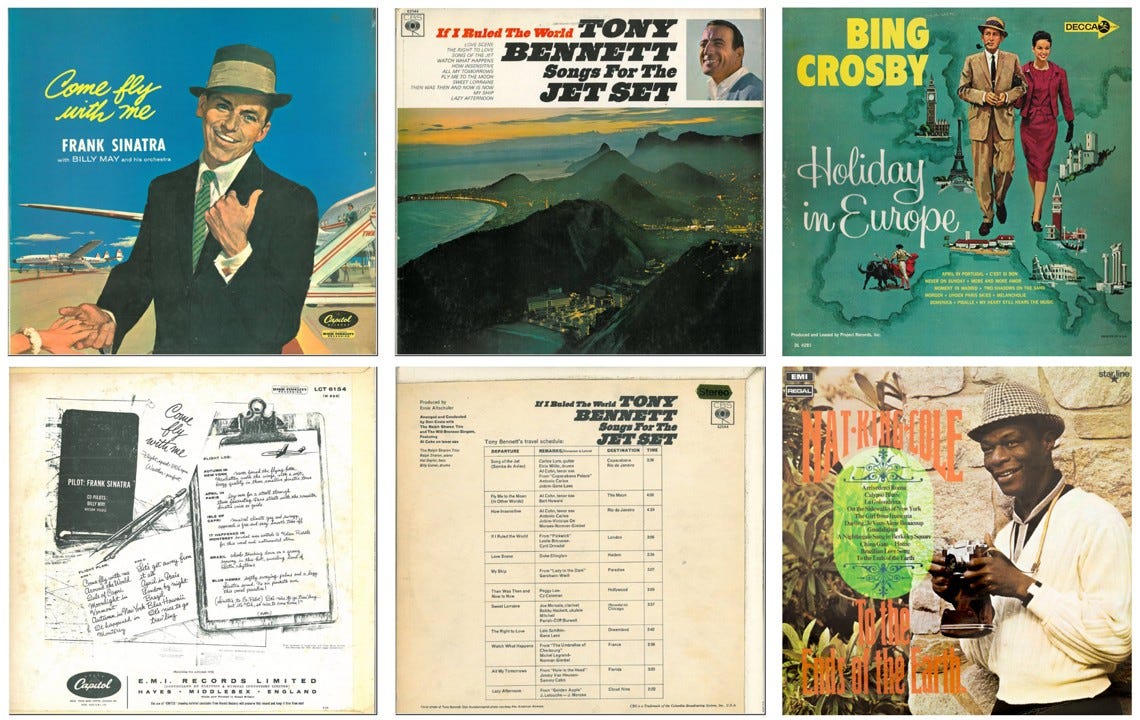

Classic examples here include Frank Sinatra’s Come Fly With Me (1958), Bing Crosby’s Holiday in Europe (1962) and Tony Bennett’s If I Ruled the World: Songs for the Jet Set (1965). These albums presented themselves as tourist itineraries. The rear cover of Come Fly With Me depicted a ‘flight plan’ (the songs), a ‘flight log’ (notes on the songs) and listed the pilots as Sinatra, Billy May and Nelson Riddle. If I Ruled the World had a similar table on the rear jacket listing ‘Departure … Notes … Destination … Time’.

I’d also include Nat King Cole’s To the Ends of the Earth in this group, though this was a posthumous compilation from 1969 that gathered place-themed recordings by Cole from across his career rather than a pre-planned concept album. Cole is shown with a camera on the cover, modelling the sightseeing tourist. He sings in Italian and French as well as English, adding to the air of cosmopolitanism the album conveys.

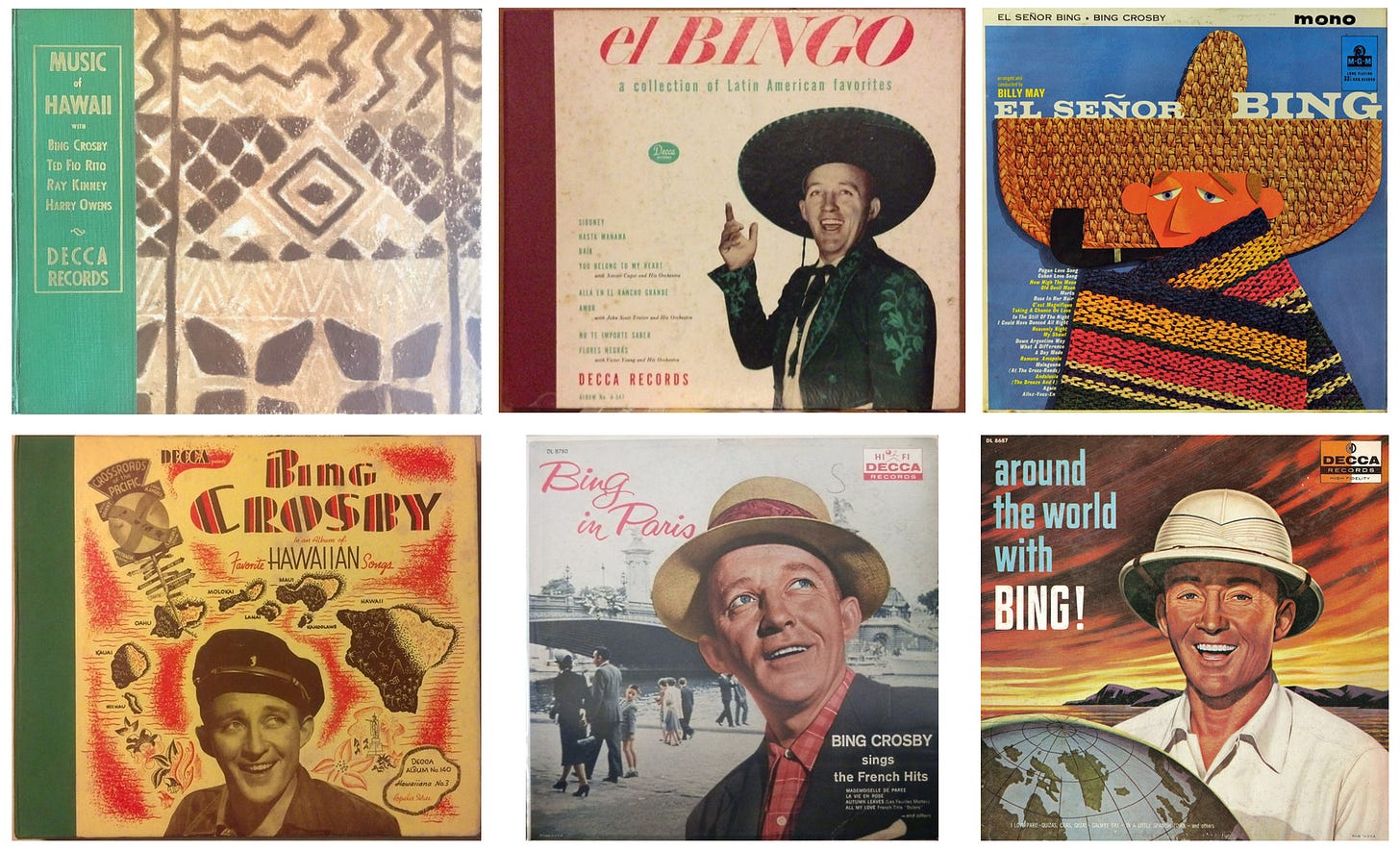

Crosby’s Holiday in Europe may have come after Sinatra’s Come Fly With Me, but the older singer already had form with travel-themed albums (and movies). As far back as 1939, two of his Hawaii-related songs had featured in an album of five 78RPM discs released by Decca as Music of Hawaii. The following year saw the release of a Crosby-only selection of Favorite Hawaiian Songs, while 1947 brought El Bingo: A Collection of Latin American Favorites. Nearer to the period I’m discussing was the similarly Latin-themed El Senor Bing (1961) and, preceding that, Bing in Paris and Around the World with Bing! (both 1958).

All these albums came with notes that promoted the places the music was celebrating or sourced from. El Bingo and El Senor Bing traded on Crosby’s position both as someone who was revered enough to be familiarly nicknamed in Latin America and as someone who was an exemplary celebrity traveller or vacationer. The rear cover of Around the World tells us that ‘Bing belongs to the world’ and describes him as a ‘sophisticated world figure’ who ‘retains a quality which is unobtrusively but unshakably American’.

I picked up on Holiday in Europe when I saw it in a charity shop partly because it’s a holiday record and partly because it includes Crosby’s recording of ‘April in Portugal’. When I was collecting holiday records, I was more likely to go for those with Portuguese songs on them for reasons my recent posts should make clear. I suppose for a while I became like Clarence, the record collector profiled in Evan Eisenberg’s book The Recording Angel, who would ‘collect anything with Clarence on it’.

Crosby’s ‘April in Portugal’ opens the album with confident ease, his phonogenic croon delivering Jimmy Kennedy’s lyric like a whispering serenade. As for the rest of his vacation, Crosby spends most of his time in France (five songs), followed by Italy (three), Greece (one), Germany (one) and Spain (one). Though we might expect more destinations from a twelve track album, there’s enough here to provide a sense of Crosby’s cosmopolitanism. The liner notes tell us that ‘Bing’s unique charm dismisses the barriers of language, culture and geography with the casual aplomb that is so characteristic of everything he does’. As with other albums in my holiday record collection, the aim of the liner notes is to present the artist as a comfortable, confident connoisseur of global culture, someone whose ‘casual aplomb’ and way of being in the world the average consumer might envy or wish to emulate.

The cover of Sinatra’s Come Fly With Me is an anomaly among the singer’s run of concept albums of the 1950s and 1960s. Where many of those had placed Sinatra in the foreground or background of street scenes, barroom vignettes, dance floors or celebrations of young love, this one has him inviting a female companion aboard a waiting plane. In the background stands a TWA jet, a bit of product placement that apparently infuriated Sinatra when he saw it. The producer George Martin, who was present for some of the Come Fly With Me sessions, reported the singer’s reaction in his memoir All You Need Is Ears:

Sinatra’s view was that Capitol were ripping him off by doing some private deal with TWA. The innuendo was that if the record went out like that the Capitol executives would get free publicity, free fares, or free something-or-other. Whatever the truth, Sinatra’s attitude was plain—TWA were getting a free advertisement out of his face. Soon after that he left Capitol and set up his own Reprise label.

Billy May’s arrangements for Come Fly With Me are upbeat, bringing sunshine to these globetrotting tales (May, by the way, also handled the arrangements for Crosby’ s El Senor Bing). In his excellent book Sessions with Sinatra, Charles Granata describes Come Fly with Me as ‘one of the jauntiest Sinatra albums of the period’. Of the opening title track, written for the project by Sammy Cahn and Jimmy Van Heusen, Granata writes ‘[It] is a lofty affair that is the perfect vehicle for Sinatra’s languid, breathy vocals, so evocative of the feeling of flight’.

The song’s lyric also has a jaunty quality. I’ve always liked the song, but I feel it’s the quality of the arrangement and Sinatra’s singing that pulls me along rather than silly lines like ‘let's float down to Peru / In llama land, there's a one man band / And he'll toot his flute for you’. It’s hardly ‘One for My Baby’, but then we’re getting the brushing-all-that-melancholy-off Sinatra here: blue eyes and blue skies rather than the long blue moments of the wee small hours.

Like Crosby, Sinatra gives himself to us as the world-traversing sophisticate, whether sourcing exotic booze in Bombay or contemplating a flying honeymoon en route to Acapulco bay. Other destinations on the album include Hawaii, Brazil and Capri. There are the common associations between times, seasons and places: Moonlight in Vermont, Autumn in New York, April in Paris, London by Night.

I have a UK mono release of the album, meaning that the first side ends with ‘It Happened in Monterey’. This song replaced ‘On the Road to Mandalay’, an adaptation of Rudyard Kipling’s poem that appeared on the original US release. Kipling’s daughter Elsie Bambridge, acting as executrix of the poet’s estate, had the song banned in the UK due to her intense dislike of it.

When I wrote recently about the versions of ‘April in Portugal’ by Bert Kaempfert, George Melachrino and Manuel and the Music of the Mountains, I explored how notions of ‘Portuguese-ness’, ‘Latin-ness’ and more general ‘foreign-ness’ were vital aspects of the music’s meaning and the way it was presented to an assumed Anglo-American public. By the time of that tune’s ascent into easy listening ubiquity, the development of jet travel was opening up new possibilities for tourists. If the singer-centred albums by Crosby, Cole, Sinatra and Bennett were still suggesting a globetrotting actor who was more able to define the jet set than the average person, the mostly instrumental albums that I class as holiday records removed that celebrity aspect somewhat, making the imagined places seem more reachable.

A sense of luxury still attended these records, however. Mantovani’s Continental Encores (1959) was a lavish affair, a genuine ‘album’ in that its gatefold cover incorporated an eight-page booklet featuring colour photographs of European tourist destinations (complete with glamorous young tourist couples) and gushing notes describing the ‘journey in sound’ contained on the record: the combination of music and recording technology, we are told, can bring Europe into our living rooms, or ‘to put it another way, it can now be employed to take you out of your home, and lead you gently by the ear to familiar or imagined places.’

Like the use of glamorous locations in films of the period, this type of holiday album presented itself, above all, as an account of something that other, more sophisticated people were doing, or that gifted musicians could make you believe you could do. These were other people’s holiday albums, which listeners were invited to peruse and to imagine being a part of.

It’s worth distinguishing between souvenir records and armchair travel records. While the former allowed tourists to purchase a sonic memory of their trip—a potential future nostalgia trigger—the armchair travel album played on the understanding that music could be escapist or nostalgic even if you hadn’t had the direct experience of the places being evoked. These aspects were often combined, as in the liner notes to Continental Encores, which contained the following two observations:

Of course, the comparative ease of Continental travel these days has helped to introduce us to French, Italian and German tunes which in the ordinary way might never have reached these shores had they not been stowed away in the memories of English holiday makers, wistfully returning from unimagined sunshine.

[…]

bring out the liebfraumilch, the frankfurters, and the apfelstrudel, and settle back in your arm-chair, for a detour that takes in O mein papa and Mutterlein, better known to us as Answer me. Also a sweep to the warm South West for the pleasure of seeing April in Portugal.

This mixing of experience and fantasy, actual and virtual travel, is reflected in Mantovani’s musical arrangements, which swoop and swoon around their source material, swelling it beyond familiar proportions or particular geography. The place this music most authentically evokes is the one we find on all the arranger’s albums: the Mantovaniscape.

Again the liner notes explain this as a deliberate objective:

To be effective, this kind of playing has to be done with tremendous skill, for the human ear would not be satisfied and convinced by the flat side of real life. The mere playing of a tune from some place or other is not quite enough. If, in the yellow-grey days of winter, we are to be carried to the spring warmth of the Iberian Peninsula, a group of musicians sawing away at April in Portugal is insufficient transport; the warmth must be in the playing, not merely implied in the title.

And so with all the tunes in this album, Mantovani produces a sort of heightened impression of the places he takes us to in his music.

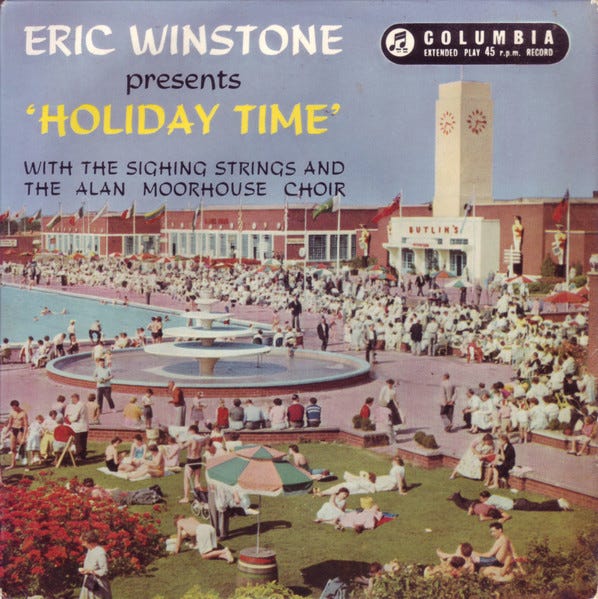

Another way that real and virtual travel was combined, in the UK at least, was in the use of bands at holiday camps to provide nostalgic music appropriate for holiday moods. One such bandleader, Eric Winstone, released an eight-track EP in 1958 entitled Holiday Time, made up of two sections: ‘Holidays at Home’ and ‘Holidays Abroad’. Once again ‘April in Portugal’ was included, leading off a medley of choral and orchestral arrangements that included ‘Wonderful Copenhagen’, ‘Vienna City of My Dreams and ‘Arrividerci Roma’ [sic]. The liner notes referred to the ‘carefree, happy-go-lucky atmosphere … maintained throughout’ and to Winstone’s ‘long-established reputation for creating and dispensing happiness, nostalgia and escapism’.

As I mentioned, holiday records share several similarities with the more heavily chronicled world of exotica and ‘space-age bachelor pad’ music in that they provide what Joseph Lanza, in his book Elevator Music, calls ‘an environmental recreation’ or ‘whirlwind tour’ based on exotic stereotypes. As Lanza notes,

Despite their vaunted weirdness, exotica and space-age bachelor pad music are almost invariably placed in the murky miscellany with the Mantovanis and [Hugo] Winterhalters. They took mood music as far as it could go but, in turn, provided a flashy doorway into the larger easy-listening manse that may seem less ‘cool’ at first but gets equally (if not more) beguiling on closer listen.

Indeed, it’s hard to distinguish between Muzak, mood music, easy listening, exotica, space-age bachelor pad music, lounge and holiday records; they all constitute Lanza’s ‘murky miscellany’. Like exotica pioneer Les Baxter, mood music outfits such as The 101 Strings and the Mystic Moods Orchestra went for feeling and mood rather than authenticity, providing an explicit fakeness, a refusal to be enslaved to the aura of the original even as their record labels and album covers promised authenticity. The basic sonic template for all such groups was interchangeable from the representation of one locale to that of another. Many featured what Borgerson and Schroeder call ‘the all-purpose European symphonic sound’ (Designed for Hi-Fi Living, p. 166).

Holiday records present the exotic, but not the spectacular exotic associated with Baxter, Denny, Lyman and Sumac. Where exotica indexes impossible fantasies beyond the borders of the wildest orientalism, holiday records showcase reachable but romanticised destinations, even if they do often settle for armchair representation. Where exotica focuses on the fantasy of adventure and the nostalgically misremembered dangers of elsewhere, the holiday record trades in the possibilities of leisurely travel and tourism and in cultural misrepresentations of a more modest kind.

Where the holiday record does trade on excess and spectacle is in its frequent recursion to massed instruments. Recalling the ‘heightened impression’ praised in those Mantovani liner notes, there seems to be a need to go for more than ‘the flat sound of real life’. Why have just a few guitars visit a locale when, like Tommy Garrett, you can have fifty? Garrett wasn’t the only person to take guitars on holiday: Buddy Merrill did too. Arthur Ferrante and Louis Teicher took pianos.

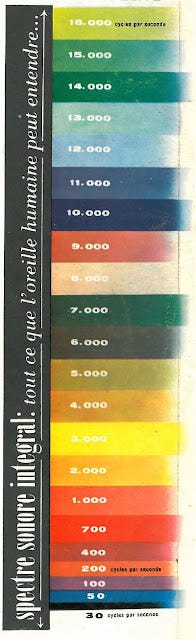

Taking instruments to new places, or having instruments evoke those places, was tied in to ongoing developments in studio sound, most obviously stereo recording. Like many of the functional, pedagogical or mood-based LPs that appeared during the 1950s and 1960s, records that focussed on holidays, trips and global tours would connect the success of their ventures to experiments in sonic technology.

To take another instrument-focussed travel record as an example, Percussion Around the World by the International ‘Pop’ All Stars offered a global tour that was facilitated by the clear stereo separation of the various instruments. As the liner notes explained,

The magic of PHASE 4 recording has brought us this superb long playing album … whose sonic brilliance and precision is truly ‘world-wide’ …

This album does more than just hold a selection of tunes denoting far away places. It attempts to capture not only the colour of a locale—which is done with a judicious use of the instrumentation—but it attempts realistically to excite the spirit native to the place from which the song originates. To hear ‘Volare, therefore is to be in Italy, to hear ‘Auf Wiederseh’n’ is to be in Germany. France can’t be more closely portrayed than it is in this LP’s interpretation of ‘Poor People of Paris’, and the list extends to such far-off places as China, Greece, South America, Austria and India.

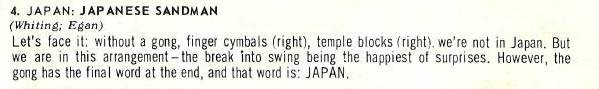

The album contains a version of ‘April in Portugal’, of course, but I said I would venture further afield in my examples, so here’s the primer for ‘Japanese Sandman’ followed by the track itself:

In thinking about what holiday records do, I find myself drawn to the metaphor of the postcard. As examples of visual and textual representation, the comparison seems apt. Postcards do several things. They mediate between senders and receivers. They promote and represent places. They do so in ways that are reductive, essentialised, sometimes ironic and knowing, at times sophisticated, at others cheap and tawdry.

The postcard one sends to family or friends says as much about the sender and receiver as it does about the place being represented on the front and the experience being reported on the rear. Postcards may be bought for oneself, of course, in which case they play the role of souvenir. They are objects which connect the here and now of buying and sending to the then and there of receiving or remembering.

Postcards are objects purchased in the knowledge of a future moment in which the present will have been reported on or recalled. They are both prescriptive and transcriptive. They are prescribed because a network of actors—photographers, illustrators, designers, manufacturers, printers, distributors, retailers—has anticipated the need for the purchase (a need, of course, saturated in ritual and precedent) and also because the postcard buyer has anticipated buying the postcard as part of their travelling experience. Postcards are transcribed because the same network of actors has attempted to get something of a place and an experience down on paper. It has committed itself to an act of documentary. Postcards imagine remembering.

Holiday records are comparable. I’m struck by how many variations on a theme there are, just as with postcards. There are attempts at sophistication, as in some of the George Melachrino and Mantovani albums, and there are cheaper, more garish examples.

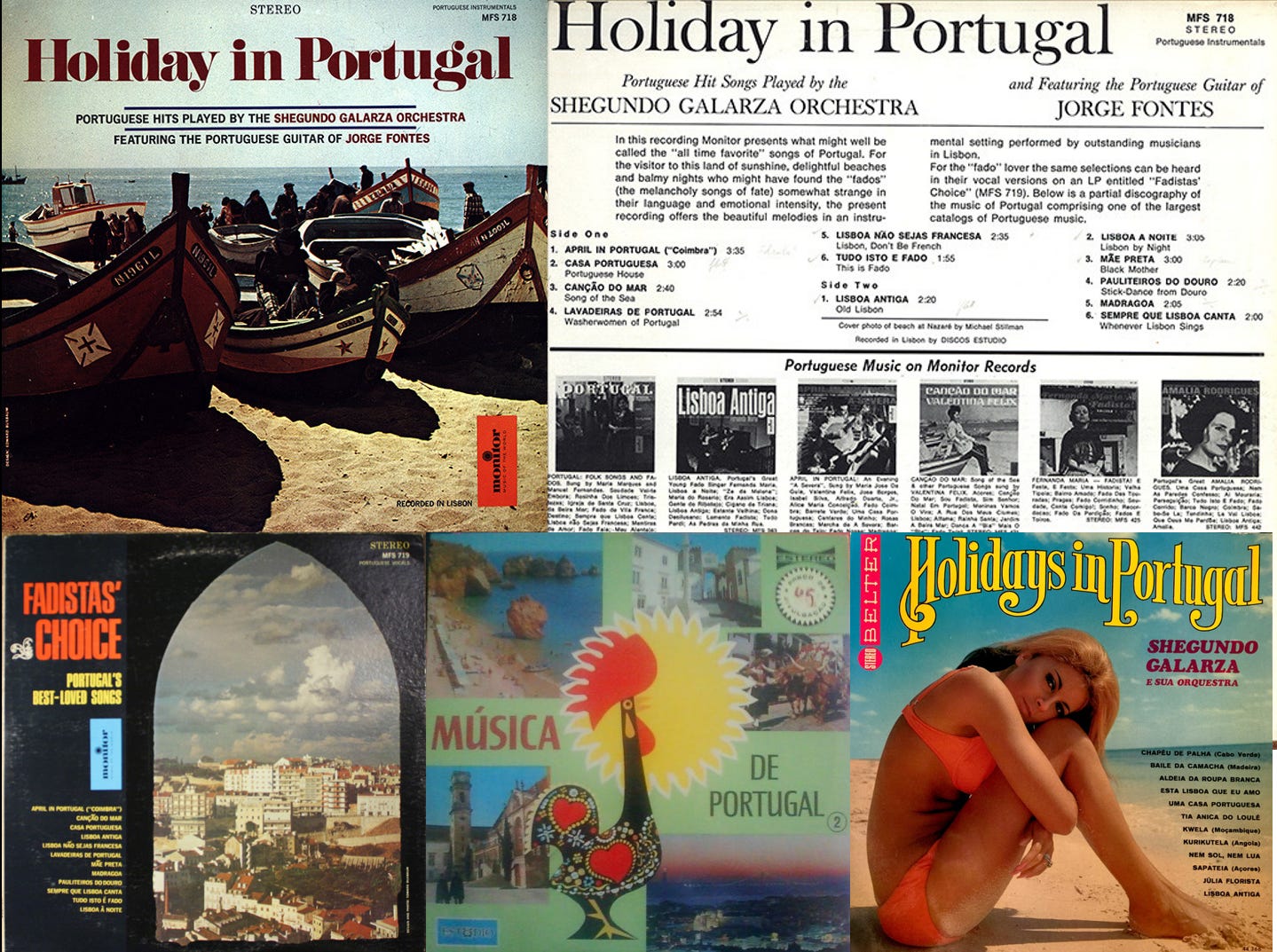

This may sometimes relate to the extent to which the album is marketed as an artist-centred one or an activity-centred one. For example, there are multiple versions of Portuguese holiday music arranged by the Basque-born bandleader Shegundo Galarza, who spent most of his career in Portugal. The album Holiday in Portugal contains instrumental versions of several fados, including the ubiquitous ‘Lisboa Antiga’ and ‘Coimbra’. Vocals are removed from these arrangements, we are told, because visitors might find them ‘somewhat strange in their language and emotional intensity’.

For the braver soul or the connoisseur, vocal versions of the same tracks are made available on an album called Fadista’s Choice. The instrumental versions are also issued on the collection Musica de Portugal, which removes reference to Galarza and the Portuguese guitarist Jorge Fontes from the cover in favour of a recreation of a Portuguese postcard. The album Holidays in Portugal, meanwhile, contains some of the same songs but is a distinct collection, again aiming for the cheap and cheerful postcard aesthetic.

The brochure is another metaphor for considering the holiday record. Holiday brochures, of course, attempt to portray the holiday experience and to paint places in the best possible light. Mantovani’s Continental Encores is one example. A more modest one is this album featuring the fado singer Lidia Ribeiro, which was privately released by the Hotel Estoril Sol and Casino Estoril as a way of promoting their businesses, as well as that of another hotel in Lisbon.

I’ve paired Ribeiro’s record above with the ‘Holiday Abroad’ series that was a collaboration between RCA Victor and the Belgian airline Sabena. Borgerson and Schroeder discuss this series and other examples of business synergies between record and travel companies.

Holiday records have never really gone away, it’s just that they are much less likely to be records these days. In their book Music and Tourism, Chris Gibson and John Connell trace the processes of virtual tourism and vicarious journeys from the holiday records of the 1960s to ambient and new age records and CDs and to what became, in the 1980s and 1990s, the genre of world music. And, as I noted in my fado book, it was easy to find examples in the world music sections of shops of what passed for holiday CDs in the early 2000s, with titles like Bar Lisbon, Bar Istanbul, Bar Bombay, Café Italia, Café do Brasil, Café Arabia.

The holiday records of the 1960s were very much part of the vinyl LP boom, where the long-playing format lent itself to grouping songs together via concepts and themes. This idea was easy to continue in the CD era. In the streaming era in which we now find ourselves, this function has been taken up via the playlist.

Nostalgia is immune to format, while format is often intimately connected to nostalgia. At the heart of the phonograph—imagined by Thomas Edison in the nineteenth century as a dictation and memorial device—is a desire to create and revisit old haunts. With each subsequent development in phonography, we find related desires, ways to summon moods and affects and to posit journeys to remembered and imagined places.

Leonieke Bolderman’s book Contemporary Music Tourism: A Theory of Musical Topophilia (2020) has productively analysed how people use playlists in services such as Spotify to imagine and plan voyages before travelling, to accompany those trips and then also to recall them later. ‘Music can be like a book or painting’, Bolderman writes,

something to be pondered over, forming the start of developing elaborate imaginary worlds. However, music experienced in its unfolding over time can also be a tool to set the mood and atmosphere of a place, used more instrumentally to enchant the physical world with that which is not present.

Music is about connection to and disconnection from the listener’s environment: for Bolderman’s interviewees, ‘Music … was used as a tool to literally tune into or out of a landscape’. This matters because we often think about music in terms of location, but we should also consider it in terms of dislocation. The dislocative possibilities of music allow it to both seem to be about or connected to particular places while equally detachable from them. Music makes us feel in and out of place.

For all the continuities, however, holiday records of the kind I once collected are anachronisms now. We’re far enough removed from the moment of production and reception that it’s hard to discover what the producers of these records intended, how the records were received and what people actually did with them. One reason I’ve found so many of these records in charity shops, house clearance auctions and other sites of the unwanted is that their original purchasers were either no longer interested in them or, more likely, no longer with us. The records themselves are ‘exhausted commodities’, to use Will Straw’s term.

Holiday records traded on escapism and nostalgia, but it was less certain whether they could become objects of nostalgia themselves. Despite the occasional lavish products released by the culture industry, one cannot easily imagine something like Continental Encores being released now; as an object seemingly forever indexed to the past, it has a nostalgic mystery to it. To take a humbler example, whenever I see a copy of Music from the Greek Islands by Tacticos and his Bouzoukis in a charity shop, I think of my parents’ ownership of this record and the holidays they took in Greece. This works by association, too, meaning I can feel that familial tug when seeing other Greek holiday records.

Mostly, though, these records have become homeless objects in a way that seems to mock their once brazen attempt to sell the pleasure of travel.

I sometimes wonder whether these kinds of records have the potential that exotica records showed to become objects of interest to those concerned with what culture discards on the road to canonising other tastes. It would also be interesting to explore notions of kitsch and abjection along the routes sketched by theorists of material culture or chroniclers of the pop’s bizarre pasts. Many of the records I own are not strange enough to make collections like Juno & Vale’s two volumes of Incredibly Strange Music, but there’s an overlap.

I wonder how the holiday records in my collection present a nostalgic reflection on leisure time itself, of travel and a certain (mis)understanding of the world.

They are representations of nostalgia, especially when considered as complete packages with liner notes, covers and marketing. They may be more important as representations of a general nostalgia than as souvenirs of particular experiences. The tourists depicted in the sun-drenched pages of Mantovani’s Continental Encores represent a general index of youth, travel, cosmopolitanism, wealth and leisure, but also a nostalgia for a time when this might have been possible.

As Edward Casey once observed, nostalgia has more to do with imagination than memory, and therefore employs invention and a priori speculation rather than accurate documentary history. What persists as documentary history in these records is a reminder that they presumably responded to a felt need of the times in which they were produced. It’s easy for us to dismiss the gushing liner notes that I’ve quoted here as baseless hype. But I suppose the distance between reality and what was being aimed for was clear back then too.

Enough people were convinced to take trips with Mantovani, George Melachrino, Eric Winstone, James Last, the 101 Strings and others to keep these musicians selling records for years. When I came to them secondhand, I should have known they were never going to be portals to alluring destinations. Despite what the notes to Percussion Around the World promised, I wasn’t going to experience the native spirit of place.

What I was getting was a connection to an earlier record buyer. Someone had purchased this musical safari in cardboard and vinyl, housed it for a while, then left it behind. I was collecting yesterday’s abandoned dreams and illusions.

Very interesting piece, Richard. Seeing those album covers brings back memories, as my mom had some. 'Exotic' foreign cultures were certainly a big thing in both records and films when I was growing up in the US in the 60s.

Wonderful article! Great examples and nice to see those classic Incredibly Strange Music books mentioned.