He could not abide the ends of days: it was one thing he had no control over. So he made an enemy of the clock, of merely human time, each night’s feeble apocalypse: that dire moment when the ring-a-ding bell must be wrapped in cotton wool and stowed away.

—Ian Penman, ‘Swoonatra: The Afterlives of Frank Sinatra’

Like all great stars, he was susceptible to the twin temptations of flattery and mythomania. But in the end, his finest work takes place at the midnight hour, when he tells the bartender that it’s a quarter to three and there’s no one in the place except you and me.

—Pete Hamill, Why Sinatra Matters

April felt like coming out of dreams. Spring finally arrived in northeast England. The birds multiplied. Daffodils succeeded snowdrops and were followed by tulips and snake’s head fritillaries. The days got longer, something you can’t help noticing in this part of the world. It felt like an odd time to be contemplating the long hours of the night and those indoor spaces where it’s always dark. That’s where I found myself, though, revisiting the gloom of the wee small hours, and all because of an anniversary I’d flagged several weeks before.

I began the month listening to Patti Smith’s ‘April Fool’ and that led to three posts on Smith’s later work. Before May brings its promises of starting over, I have two more April-related stories. One, slightly postponed by the Patti series, is about ‘April in Portugal’, a major hit of the early 1950s that wore its travels and changes in ways that are worth recording. Before that, though, I’m spending some time with an album that appeared seventy Aprils ago.

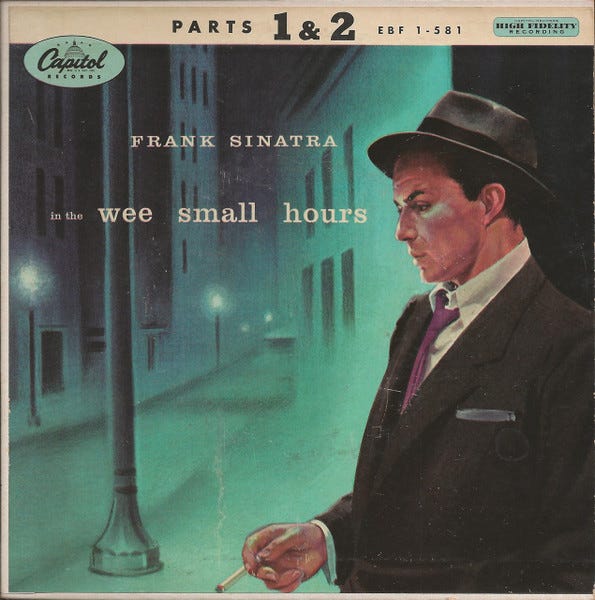

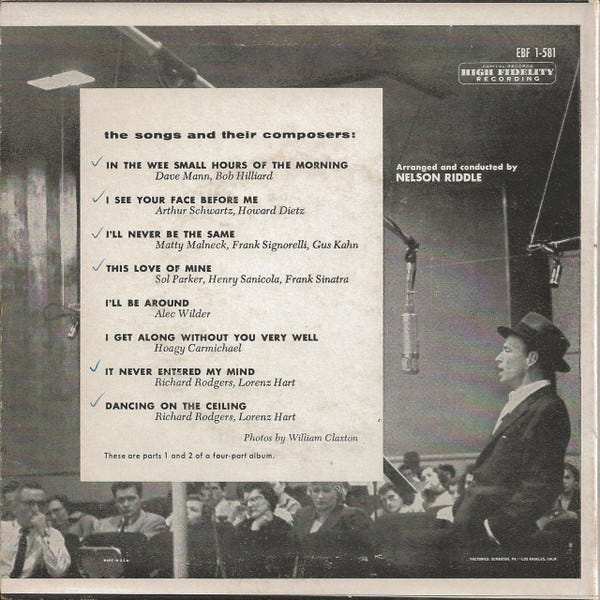

Frank Sinatra’s In the Wee Small Hours emerged from the long nights that served as its inspiration, and from those spent crafting its sonic perfection in the studio, to face the light and the public in April 1955. It was Sinatra’s third album for Capitol, following Songs for Young Lovers and Swing Easy (both from 1954). Where the first two were eight-song affairs released as 10-inch records, Wee Small Hours doubled the length to sixteen tracks, appearing as two 10-inch records, four 7-inch EPs and, importantly, as a single 12-inch LP.

The LP, which had appeared in the late 1940s and came of age during the following decade, was a technological event that helped to secure Sinatra’s persona and was arguably as crucial to his mature art as the microphone had been to his early career. It allowed for the concept album, which allowed for the crafting of time and narrative and brought cohesion to his major projects.

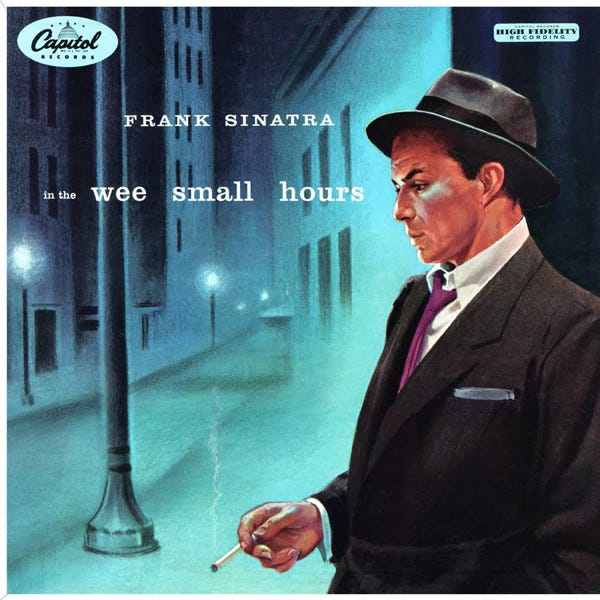

If we consider In the Wee Small Hours as a concept album, it’s as well to start with the cover, which depicts Sinatra in suit, tie and hat, leaning nonchalantly against a building on a night-time street. We see him from the side, left profile. He’s not looking at us but at the ground in front of him, lost in thought. His preoccupation extends to the lit but neglected cigarette held between two fingers of his right hand, down by his side and almost out of the frame.

Sinatra’s positioned to the right of the frame. The rest of the cover is taken up by the blue-lit, deserted street, with a prominent lamppost to the left. The lettering on the cover carries Sinatra’s name, further identifying him in case his familiar face and ‘uniform’ were not enough. The album title, meanwhile, reinforces the time of day depicted in the picture, recognisable despite the stylised buildings and lights: in the wee small hours, all lowercase, the last three words in much larger font than the first two.

The general blueness of the cover evokes a noir world but also plays on the general sense of blueness that was a pervasive mode of melancholy by this time. As Richard Williams has noted, ‘No colour has so saturated music over the last hundred years, while permitting so many shadings’. In the Wee Small Hours, in both title and cover imagery, is a fine example of what Williams calls ‘the blue moment’.

Will Friedwald notes the album’s jazziness, highlighting frequent deviation from melody and much playful musical exploration. Friedwald suggests that the musical dynamism somehow contradicts the moody, static film noir aspect of the cover, though I would argue that the noir world is also a jazz world.

If there’s a contradiction between the cover of Sinatra’s album and its contents, it’s the suggestion that the singer is outdoors, whereas the mood is one of being indoors with the lights dimmed.

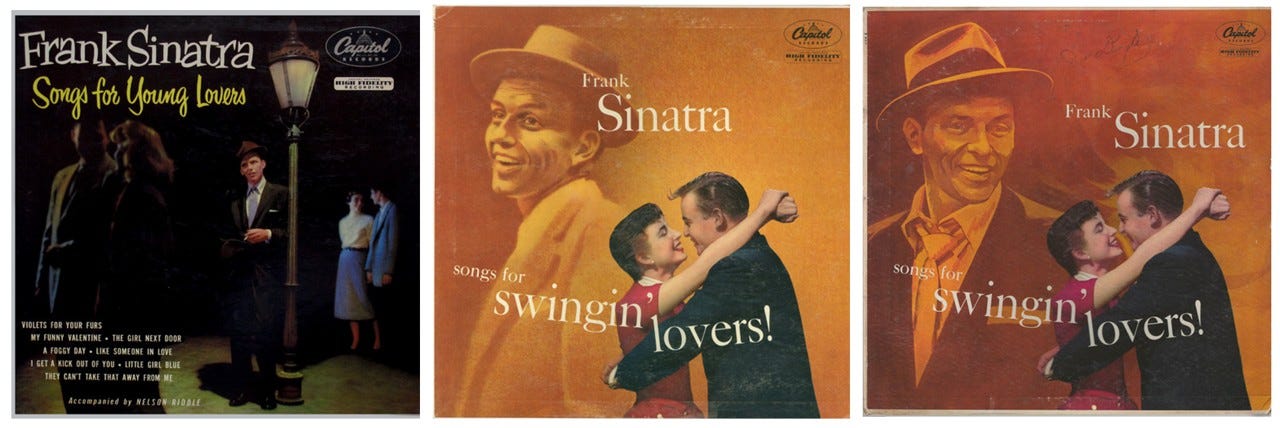

The picture provides continuity, though, taking its place in a series of Sinatra album covers that feature the singer as detached observer of the world around him. The year before, he’d stood by another lamppost watching the young lovers for whom he’d offer his songs. The following year he’d be a ghost-like figure haunting a new pair of swinging sweethearts (initially, in the 1956 cover, facing away from them; on subsequent versions, looking towards them, still removed from their world). Later albums will place him alone at the bar while other patrons carouse, or paint him as a tragic jester, hiding his tears behind the make-believe of comforting those same carefree couples.

To the songs of In The Wee Small Hours. The title track is the opener. It’s narrated in the second person throughout. The ‘you’ who’s lying awake, thinking of an absent lover, the repentant whose ‘lonely heart has learned its lesson’, could be the singer addressing himself, but it’s also a shared ‘you’, a description of the type of person who, it seems, always has to relearn this lesson.

The realisation that the wee small hours are the time you miss your lover most of all could come from immediate experience—the autopsy of a newly dead relationship—or from longer, accumulated experience, the knowledge that this happens repeatedly, that it’s always this time of the night, or morning, when the feeling returns.

Placing ‘Mood Indigo’ after the title track strengthens the sense that we’re hearing from an experienced loser in love; the lines ‘you ain’t been blue / till you’ve had that mood indigo’ seem to speak from a place of repeated rejection and dejection, a site of endless blue moments.

While these songs evoke disappointment in such a predicament, ‘Glad to be Unhappy’—a song memorably performed by Billie Holiday on 1958’s Lady in Satin—finds the narrator wallowing in the perverse glee of being down. He has unrequited love ‘pretty bad’ but feels that ‘for someone you adore, it’s a pleasure to be sad’.

The fourth song on the album, Hoagy Carmichael’s ‘I Get Along Without You Very Well’ (also memorably performed by Holiday, and later by Nina Simone), attempts another perspective on absence. This time we get a narrator who initially tries to fool himself, and the listener, into thinking everything’s alright, that he can find balance and normality in life after the relationship. But the truth of the song lies in the list of exceptions to this newfound ability to get along: ‘except when soft rains fall’, ‘except when I hear your name’, ‘except perhaps in Spring’.

These songs establish the blueness that pervades the sixteen tracks of In the Wee Small Hours. The hue isn’t always monochrome. As Friedwald notes, the strings, horns and piano sometimes dance ahead of or between the lines, throwing in a sense of jollity that might seem at odds with the aura of doom that pervades the stories being voiced. I think these sounds can be heard as the background bustle of normal life that continues apace around the singer as he narrates his tales of woe, or as the party in the bar that must go on despite the despondent man in the corner pouring out his blues, or the wedding party that’s in full swing while the ancient mariner delays a guest outside in order to unburden himself of his past and his guilt.

Sinatra’s barroom raconteur anticipates another who will appear nearly two decades later on Joni Mitchell’s album Blue, an old romantic who’s ‘cynical and drunk and boring someone in some dark cafe’. The tinkling piano that plays behind Sinatra in ‘Glad to Be Unhappy’, meanwhile, anticipates the piano playing ‘Jingle Bells’ that lurks behind Mitchell’s otherwise gloomy ‘River’ and, prior to that, Nina Simone’s interpolation of ‘Good King Wenceslas’ into her version of ‘Little Girl Blue’ (a blue moment that Sinatra himself had essayed on Songs for Young Lovers).

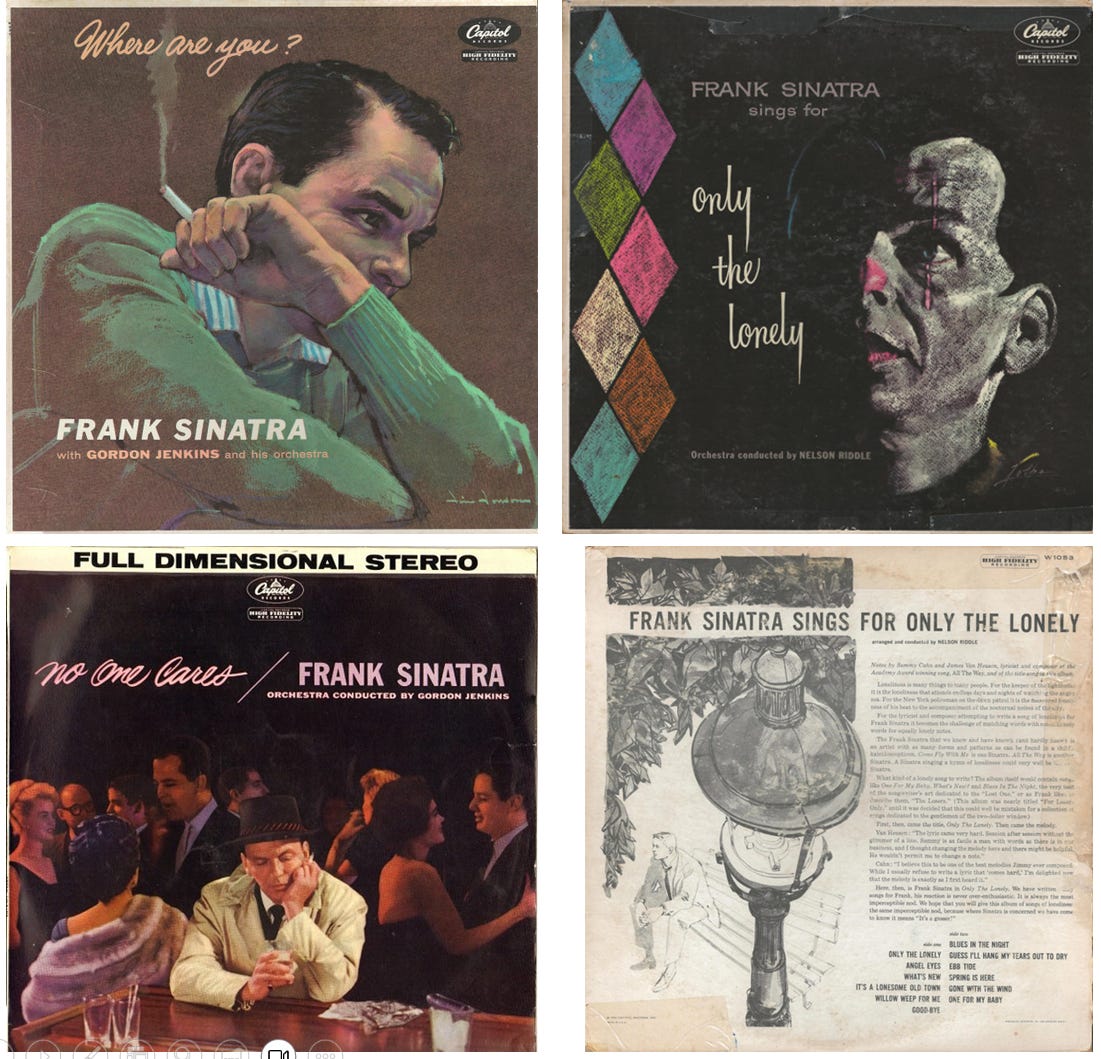

As Sinatra sings these hymns to doomed love, he highlights the importance of rhythm in singing. In up-tempo numbers from other albums—‘You Make Me Feel So Young’, ‘Young at Heart’, ‘I’ve Got You under My Skin’—rhythm is crucial to the vocal delivery; the voice has to keep to time, to stay rhythmic and melodic, in order to deliver the lines effectively. What I hear on a lot of Sinatra’s slow ballads, and in particular the doomier songs of In the Wee Small Hours, Close to You (1957), Only the Lonely (1958) and No One Cares (1959), is a severe loosening of the rhythm.

The sense of losing time seems to echo what can happen when drunk or depressed, a feeling of being liberated from temporal norms. This is another thing that connects Sinatra to Holiday, for this freeing of the rhythmic line is one of her legacies. From the listener’s perspective, it’s more difficult to follow, and to sing along with, these meandering songs.

I feel Sinatra’s upbeat songs sound the way they do because having to stay on top of things demands a kind of business-like efficiency. I don’t mean that Sinatra’s sunnier songs are short of vocal brilliance. Far from it. They’re all about brilliance, meaning both excellent vocal technique and light-filled disposition. It’s just that, with the gloomy songs, consummate control comes with a side order of excommunication, as if the singer’s been released from the everyday time of bearing up.

Sinatra is still displaying mastery amidst the vulnerability, his singing suggesting that voice can deliver a reliability that romantic relationships cannot. When he stretches the first word ‘straying’ in the line ‘like a straying baby lamb’ (‘Glad to Be Unhappy’), when he elongates the first syllable of ‘ages ago’ in ‘Last Night When We Were Young’, or when he provides an emotional uplift to ‘Oh, the night!’ in ‘This Love of Mine’, he is escaping the vulnerability of which the lyrics speak by showcasing deft control of breath, tone and phrasing.

If this is a victory for the singer, it’s not necessarily so for the listener seeking solace, reflection or identification. And it’s the listener who is likely to spend the most time with this material in this order, merely by playing and replaying the album. That there are sixteen songs on In the Wee Small Hours makes us feel we’ve spent a long time with Sinatra, that we’ve shared a long night of the soul.

Sinatra would ask us to spend more such nights with him, on subsequent albums Close to You and Only the Lonely. When these albums are discussed together, as they are in Will Friedwald’s book Sinatra! The Song Is You, they can be seen as presenting different emotional hues:

Wee Small Hours was hardly all gloom and doom, apart from ‘Last Night When We Were Young’ (and even that bears a pregnant-with-hope pause); it suggests a dark point that we hope will be followed by the dawn. Close to You depicts that sunrise, with Sinatra’s protagonist refusing to wallow in self-pity but rather taking a self-deprecatingly bittersweet look at his own romantic foibles. The singer then painted what many consider his greatest ballad collection, Frank Sinatra Sings for Only the Lonely, in colors so pitch black that no light could possibly escape.

This is partly achieved, as Friedwald records, by the loosening of the tempos of the songs and by the use of rubato in places. The result is a kind of drift, reminiscent perhaps of a drunken night of maudlin self-reflection. In such times the mind goes wandering and, with some songs on Only the Lonely, it seems this wandering is adopted by the restless body too as it goes in search of places of escape, only to find sites of painful memory. That place might be the bar (as in ‘Angel Eyes’) or the small cafe that ‘only the lonely know’ (‘Only the Lonely’), or it might be the streets of the city that tempt you to lose yourself and let your footsteps trace out a new map of existential despair.

‘It’s a Lonesome Old Town’ is one such song, the singer wandering the wastelands of his town and his mind. Friedwald connects this wandering to the voice and its instrumental accompaniment: ‘the two voices, Sinatra and his shadow, [trombonist] Sims, wander about this godforsaken landscape aimlessly in search of love but finding only an abyss of nothingness.’

This sense of nothingness is also there at the closing of ‘Angel Eyes’ when Sinatra sings ‘excuse me while I disappear’, a line which reflects on the protagonist in the song’s lyric who’s been drinking himself into oblivion and encouraging those around him to do the same. It’s also a reflexive moment for Sinatra, who does indeed disappear as his voice brings the song to a close.

‘Good-Bye’, closing the first side of Only the Lonely, is an excellent example of Sinatra’s vocal dynamics. I wrote about it last year in my post ‘Sixteen Song Moments’, focussing on the part where the mellow reminiscence of the song’s studium is punctured by Sinatra bellowing ‘but that was long ago’, then dipping back to melodic reflection for ‘you’ve forgotten I know’.

‘Spring Is Here’, another melodrama from Only the Lonely, centres on a repeated ‘Nobody loves me’ refrain. As in many popular songs, Spring is presented as the season of hope, a time when one should be delighted by the world. But it cannot delight Sinatra’s protagonist, who’s alone. The rediscovery of the world that one can experience with a partner has disappeared. The following ‘Gone With the Wind’ intensifies the mood of loss. The album closes dramatically but enigmatically with ‘One for My Baby’, a performance described by Roger Gilbert as ‘an intricate vocal dance of defensive bluster and wounded retreat’:

If Sinatra’s first impulse as a young singer was to master breath control so that he could produce long, continuous, legato lines free from artificial pauses, his second impulse was to learn where to put the pauses so that they could speak as forcefully as the words. But it’s the way the very grain of his voice reveals precisely how and where his contradictory selves are joined, shows us the seam or scar that connects and divides swinger and loser, that makes this record such a monumental work of expressive art.

Mastery may be experience’s gift, but it’s also born of a desire to overcome vulnerability and anxiety. Compulsive repetition of acts of mastery can lead back to a position of vulnerability. This tension presents itself in the figure of the man-of-experience slumped at the bar, well illustrated in the musical worlds explored by Sinatra and Hank Williams. David Brackett writes of Williams:

The very phenomenon of the ‘vulnerable’ male (an image circulated widely at the same time in Tin Pan Alley popular music as well), frequently perched on a bar stool in a honky-tonk, constituted one of the recurring figures of the honky-tonk style. If the expression of loss does carry with it conventional associations of femininity, then the use of those conventions by males is something of a convention itself during the period of Williams’ ascendance to popularity.

It’s interesting to note Brackett’s connection here between honky-tonk and Tin Pan Alley. And it is also worth noting that the image Brackett describes has continued to have a long history in the period since Williams’s heyday. Indeed, the cowboy provides a crucial mytheme for several popular song genres, from rock through reggae to hip hop. Cowboys and cowboyism have long provided male rock (and other) musicians with a romantic role model of the loner, the outlaw or the man true to himself. While Frank Sinatra may not have obviously presented himself as such, there is something cowboyish about his late 1960s persona and his posse of Rat Packers.

Cowboyism, while supposedly basing itself on the image of the ‘real’ man, also evokes notions of play, and this connection marks a paradoxical position of vulnerability in which the man becomes a child again. Vulnerability and projections back to more innocent times were staple features of several Sinatra’s concept albums, such as Where Are You? (1957), No One Cares (1959), All Alone (1962), September of My Years (1965), Cycles (1968), A Man Alone (1969) and Watertown (1969). Chris Rojek suggests that, even though Sinatra went through a variety of stages in his career, at a certain point he seemed to remain the same man:

Between the ages of 38 and 70, that is, during the period between 1953 and 1985, there was a sense in which Sinatra decided to put the ageing process on hold. In these years he was a sort of middle-aged adolescent.

I would add to this a suggestion of a constant dialogue between the ‘vulnerable’ qualities associated with the youthful Sinatra and those associated with the confident mastery of his middle age. Roger Gilbert writes of a similar relationship between ‘the swinger and the loser’ in Sinatra’s work. This is something that continues into the 1960s, by which time Sinatra seems prone to a certain amount of repetition when exploring these tensions.

I’ll return to that topic and that era later in the year when I plan to publish another Sinatra anniversary essay, this time about September of My Years. To close this piece, though, I want to connect two things I mentioned earlier: Sinatra album covers and the album as an invitation to share time and mood with a singer.

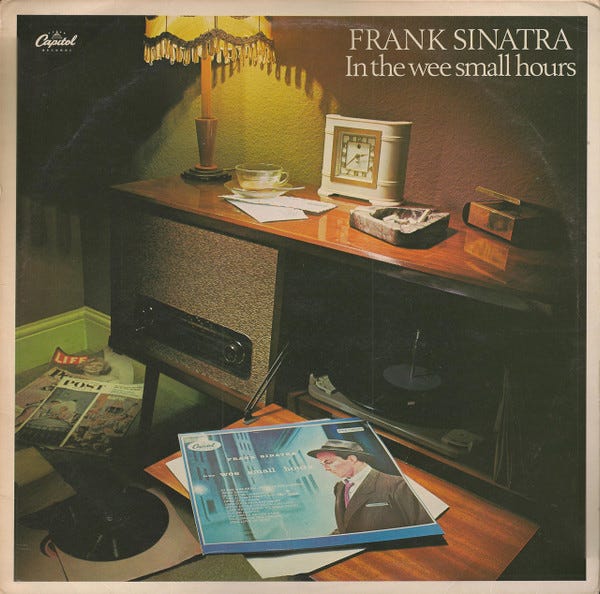

I talked about the iconic cover of In The Wee Small Hours as an invitation to an extended blue moment. But my own vinyl copy of the album is the one reissued in the UK and New Zealand in the 1970s (and again the following decade). It has an alternative design that eschews the original street scene for a domestic interior.

I like the way Ian Penman describes this sleeve’s ‘line-up of allegorical objects’ in his brilliant ‘Swoonatra’ essay:

At the centre of the front-room still life is a stately radiogram, anticipating our own scene of listening. A thick onyx ashtray, already lined with butts. A clear Pyrex cup … Art Deco clock, reading somewhere around 2.39 a.m. LIFE magazine with a Marilyn cover. Selection of shiny LP sleeves scattered over the rug. Best of all—there among them is the original US sleeve of In the Wee Small Hours! All these hallowed objects add up to something like an Eisenhower-era retouch of Dürer’s Melancholia: alchemical union under the cold urban stars.

Penman has one thing wrong here. It’s not the original US issue of the album that features in the new line-up, but a 1962 abridged version of the album with only twelve of the original tracks. (For a rigorous, audiophile-focussed history of the various lives this album has had, see Matthew Lutthans’ account of his favourite album).

The general point holds, though, that this strange packaging brings a shift of focus from the singer to the listener. The listening space becomes iconic, nostalgically recalled as a mid-century modern set-up, the sort of ambience Joseph Lanza writes about so well in his book Elevator Music.

It’s no longer about a singer alone in the street, the saloon or the studio. It’s about you, the listener, and what you need to do when that mood indigo comes creeping. You don’t think about the lover who has gone. You don’t wait for the call. You don’t spend time wondering whether your heart has learned its lesson. You put the needle on the record, or you press ‘play’. You recall what Pete Hamill called ‘the music that Sinatra loved most, the music of the hours after midnight’. And you sink back into the early morning sound of seventy Aprils ago.

It's A Man Alone for me, love that album, the spoken word interludes, late night companion, it's kin to Tim Hardin's Suite For Susan Moore, both albums are regularly played in my own personal ergosphere.

I used to facetiously say I was more a Buddy Greco man, but time has disabused me of that frivolous idea. Frank grows with the years.

A nice piece Richard.

I love Sinatra’s late night, melancholy albums. “No One Cares” is my favorite but they’re all wonderful.