I’ve been heartened by the positive response to my post on Frank Sinatra’s In the Wee Small Hours. Thank you to all who liked, commented and/or subscribed. It encourages me to continue with my planned post on September of My Years (aiming for August for that one to mark the sixtieth anniversary) and to publish other thoughts I’ve had on Sinatra over the years.

There’s a tangential link to Sinatra in the post I’m planning for next week, which will be on holiday and souvenir records. Today’s post is a kind of set-up for that one and also concludes my recent run of April-themed posts. And yes, I know it’s May now. But in my mind, it’s still April in Paris, Portugal and The Waste Land.

This essay is part of my occasional series of song itineraries. It’s about one of the biggest hits of 1953, and it discusses where that song came from and where it subsequently travelled. The cast of this story includes an iconic fado singer, a world-famous jazz trumpeter and singer, a pioneer of exotica, a Bollywood movie, a Yorkshire-born bandleader masquerading as a Corsican, and the man who wrote the lyrics to ‘Teddy Bears’ Picnic’.

The song is ‘April in Portugal’, though it began life as ‘Coimbra’. Here’s what happened.1

From ‘Coimbra’ to ‘April in Portugal’

Portuguese composer Raul Ferrão wrote the music to ‘Coimbra’ at the end of the 1930s but the tune lay dormant until 1947, when, with the addition of José Galhardo’s lyric, it was performed by actor and singer Alberto Ribeiro in the film Capas Negras. The film’s female lead was played by Amália Rodrigues, a rising star of fado in Portugal and abroad. It was one of several acting roles taken by Amália on her path to becoming the preeminent fado singer of the twentieth century and the most famous Portuguese popular music artist in the world. (My ‘All of This Is Fado’ posts provide further background to the genre and to Amália Rodrigues).

‘Coimbra’ appears in the film as a serenade delivered by Ribeiro’s character to Amália’s. It’s what I call an ‘associative’ lyric in that it’s mainly a list of features associated with the historic university city of Coimbra. Capas Negras is set amongst the students and faculty of the university, and the town is one of the main ‘characters’ of the film, not only in the depiction of its scenery but also through several mentions of Coimbra in the script. The song fits with this theme by hymning the ‘Coimbra of the Choupal [a tree-lined avenue] … of songs … of doctors’ and declaring the city to be ‘the capital of love in Portugal’.

‘Coimbra’ might have travelled no further. It wasn’t a significant hit with audiences beyond the movie theatre. Amália maintained a fondness for the song, however, and kept it in her concert repertoire. Performing in Ireland in 1950, she met the French singer Yvette Giraud, who had two of Amália’s songs adapted to French by the chanson writer Jacques Larue. One of these was ‘Coimbra’, re-titled ‘Avril au Portugal’, for which Larue provided a new lyric to Ferrão’s music rather than translating the original. The new song became a nostalgic glance back at a fleeting romance voiced by a French traveller to Portugal.

Giraud’s recording was a hit in France and the song’s popularity spawned other versions by Elyane Dorsay, Anny Gould and Yvonne Blanc. It was common practice at the time for music publishers (in this case, Chappell) to capitalise on a successful tune by having artists on different record labels record simultaneous versions.

A Dutch recording of the song appeared soon after, titled ‘April in Portugal’ and with lyrics by Jack Bess which I believe are a Dutch adaptation of the French chanson. The version released by Metropolis Amusements-Ensemble, with a vocal by Jan Verbraeken, is styled as a bolero, further internationalising the tune.

Following the success of ‘Avril au Portugal’, in 1952 Chappell approached the Irish-born, New York-based songwriter Jimmy Kennedy (author of the lyrics to ‘The Teddy Bear’s Picnic’) to write an English version called ‘April in Portugal’, a title which was already in use by some bands. Kennedy took on the job but refused the title, wanting to avoid becoming known as a writer of ‘geographical songs’. Instead, he wrote a song called ‘The Whisp’ring Serenade’, whose lyric bore no mention of any place other than poetic allusion to the moon and stars.

The protagonist of the song recounts a tale of falling in love with a piece of string music, which comes to act as a surrogate for a lost lover: ‘old ecstasy returned / I lived and loved and learned / but then you went’.

The song remained both a self-referential serenade and a tale of memory and longing, but all references to Portugal had vanished. Georgia Carr’s recording (with Nelson Riddle’s orchestral arrangement) is arguably the standout version of this point in the song’s journey.

Despite heavy promotion of Carr’s recording and a version by Rino Senteri that mixed Larue’s and Kennedy’s lyrics, ‘Whisp’ring Serenade’ was not a commercial success. Chappell offered Kennedy an ultimatum: either rewrite the song as ‘April in Portugal’ or the publisher would find someone else to do the job. Convinced by the generous fee on offer, Kennedy quickly wrote the new version, in the process creating one of the most popular songs of 1953.

Bigger than ‘Blue Tango’

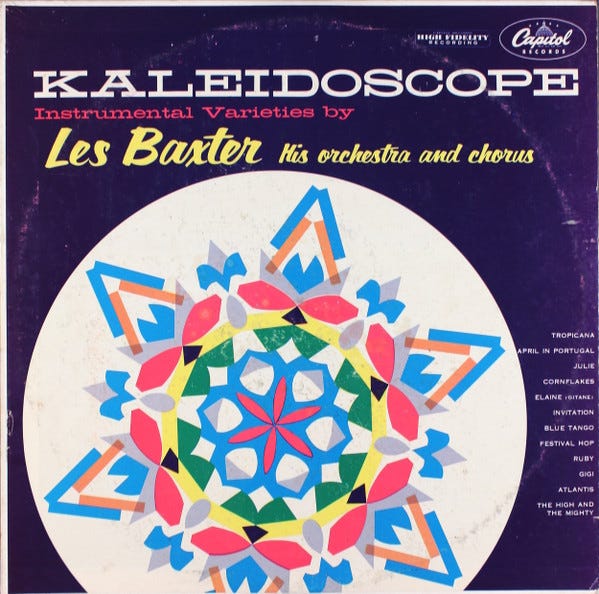

The biggest hit version of ‘April in Portugal’ came not from a singer, but from an instrumental arrangement by Les Baxter, who took the tune to no. 2 in the American Billboard chart in 1953. Freddy Martin’s orchestral arrangement had appeared earlier, but it was Baxter, a rising star of what would come to be known as ‘exotica’, who made the impact.

I’ll come back to Baxter’s version later. For now, let’s stay with the song’s onward journey. By April 1953, when Vic Damone’s recording was advertised in Billboard as being the ‘first version with new lyrics’, ‘April in Portugal’ was well on its way to becoming ubiquitous in the USA; in fact, Damone’s version had to vie with several vocal renditions, including those of Louis Armstrong (who also provided a trumpet rendition of the melody), Eartha Kitt (who combined the French and English lyrics) and Tony Martin.

The song was also a hit across Latin America the same year, with Spanish-language and instrumental versions (from mambo to tango) being produced by Perez Prado (based in the USA by then), Oscar Alemán and Bobby Capó. As ‘Coimbra’, the song had already been a notable success in 1952 in Brazil, where there was no need to change the Portuguese lyrics.

Amália didn’t miss out on the popularity of the song, appearing on Eddie Fisher’s American show ‘Coke Time’ twice in July 1953 and performing a version of ‘Coimbra’ that combined Galhardo’s original lyric with Kennedy’s English version.

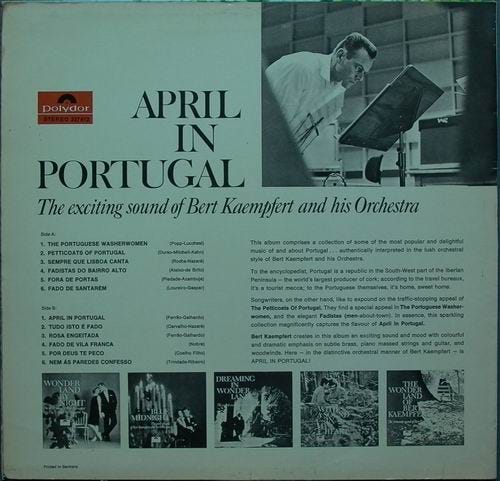

Over the following decade, more versions followed from Xavier Cugat (1957) George Melachrino (1958), Bert Kaempfert (1959), Manuel and the Music of the Mountains (1961), Bing Crosby (1961) and Joe Quijano (a ‘chachacha-twist’ version from 1963).

The song’s global reach was evident with the 1956 Bollywood film Bhai Bhai, in which the character Sangeeta (played by Shyama) danced and lip synched to Geeta Dutt singing ‘Aye Dil Mujhe Bata De’ (written by Madan Mohan and Rajendra Krishan). In the middle of the song the familiar music to ‘April in Portugal’ appears (just after the 20-second mark in the clip below; the full movie clip can be seen here).

There was also a Japanese language version of the song, courtesy of Yvette Giraud, the French singer who had done as much as anyone to set the song on its international journey by performing ‘Coimbra’ as ‘Avril au Portugal’. Having gained a sizeable audience in Japan, Giraud re-recorded some of her most popular numbers in Japanese.

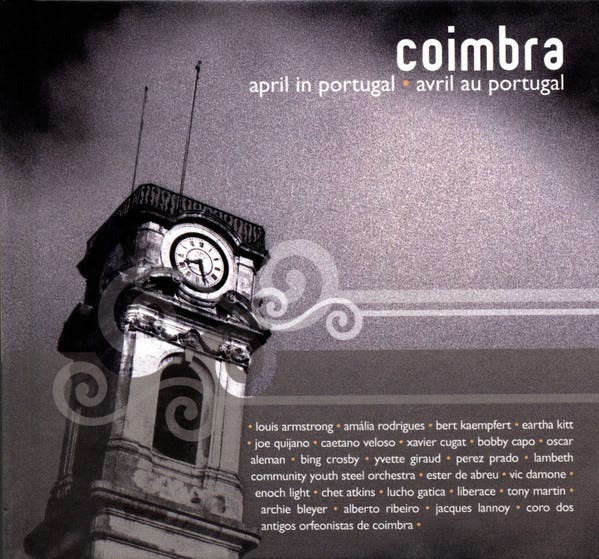

In 2004, the Portuguese record label Tradisom released a CD entitled Coimbra – April in Portugal – Avril au Portugal, featuring 24 versions of the song selected from a list of over 200 known to compiler José Moças. Besides several of the aforementioned recordings, the collection included others by Liberace, Caetano Veloso, and a version in Italian sung by Amália in 1974.

Time, Distance and Longing

Outside of the more dance-oriented instrumental versions of ‘April in Portugal’, the one constant amongst the myriad recordings of the song is a sense of longing. This association begins with the original song, with its romanticised depiction of Coimbra, students, youth and love. As a city, Coimbra had long maintained such associations, not least through the tradition of black-caped male students serenading young women from outside their windows (the source of the ‘capas negras’ of the film). In a 1931 review of fado recordings from Coimbra, the British folklorist Rodney Gallop was keen to connect text and context by describing the city, where, ‘[o]n full-moon nights you may see the students in their black gowns wandering through the dim white streets, and hear them singing to the silvery accompaniment of the guitarra the haunting strains of the fado chorado’.

As I wrote recently, one of the principal aspects of fado is saudade, the famously untranslatable Portuguese term that describes variations of nostalgia, yearning, and longing. ‘Saudade’ is the last word in the lyrics of ‘Coimbra’, meaning that the song resolves with a direct reference to this typically Portuguese framing of nostalgia.

In terms of metre, verse structure and so on, even allowing for certain differences between the Lisbon and Coimbra fado styles, ‘Coimbra’ is not a traditional fado. By mid-century, however, the growth of fado canção (‘song fado’) had made distinctions between fado and other popular styles blurry, and Amália more than anyone would develop this lack of easy distinction.

Whether in the Coimbra or Lisbon fado styles, the guitarra portuguesa is essential. In Capas Negras, Alberto Ribeiro is shown playing a guitarra while he sings ‘Coimbra’, but he’s not heard doing so; the music comes from orchestral strings on the film’s soundtrack. When Amália performed the song in her subsequent concerts and recording sessions, the guitarra returned and she typically performed it in a conventional trio style (voice, guitarra and viola [Spanish guitar]). The vocal style, too, could be heard as fado—Coimbra-style for Ribeiro, who stays closer to bel canto; Lisbon style for Amália, who offers a typically grainier vocal—though again there’s potential vocal slippage between fado and other song styles.

Ultimately, the song became a fado because it was part of Amália’s ‘Portuguese’ repertoire, distinct from the rancheros, flamencos, chansons, Hollywood show tunes and canzone Napoletana that she also performed. But all the while, gaps were opening up: between tradition and commerce, between original and adaptations, between the targets of nostalgia that the song was aiming for.

From ‘Fado’ to Holiday Record

The many versions of ‘Coimbra’ and ‘April in Portugal’ take on the baton of nostalgic representation and, through further slippages, produce new meanings. Of the early non-Amália versions of ‘Coimbra’, Les Baxter’s might, surprisingly, be the closest to fado because it uses what Baxter later recalled as ‘Brazilian mandolin’. The instrument, presumably a bandolim, provides the melody in the first part of Baxter’s ‘April in Portugal’, before the tune settles into a more conventional string arrangement. It’s both ‘exotic’ and indexically linked to Portugal and the guitarra portuguesa because of the similarity of the bandolim’s tone and playing style.

Baxter would later claim that the style he adopted for ‘April in Portugal’ would provide a template for much of his subsequent work, though that work would aim at representing far more mythically fantastic and unreachable locations than the Iberian Peninsula. Indeed, Baxter was a pioneer of the exotica style that would be taken up by musicians such as Martin Denny, Arthur Lyman, Yma Sumac (with whom Baxter worked), Sondi Sodsai and Juan Esquivel.

Esquivel, by the way, released a startlingly arranged ‘April in Portugal’ on his 1958 album Four Corners of the World.

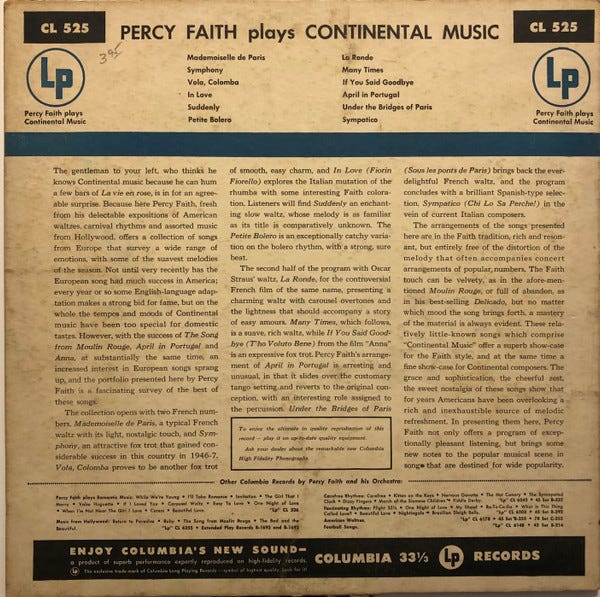

Les Baxter’s version of the song did much to establish it as an instrumental standard and many other bandleaders and arrangers would incorporate it into their repertoires. In 1953, Percy Faith included ‘April in Portugal’ on an EP and LP entitled Percy Faith Plays Continental Music. It can be taken as a sign of how widely Ferrão’s ‘fado’ melody had travelled by this point that the liner notes describe Faith’s arrangement as ‘unusual, in that it slides over the customary tango setting and reverts to the original conception, with an interesting role assigned to the percussion’.

I’m not sure what this ‘original conception’ was, though the use of military drums throughout the arrangement signals that it has little to do with fado, which rarely includes percussion. Also of note from the title of Faith’s record and its liner notes is the use of the term ‘continental music’. The notes maintain that ‘not until very recently has the European song had much success in America’, but that, ‘with the success of The Song of Moulin Rouge, April in Portugal and Anna, at substantially the same time, an interest … sprang up’. They conclude with the observation that ‘the grace and sophistication, the cheerful zest, the sweet nostalgia of these songs show that for years Americans have been overlooking a rich and inexhaustible source of melodic refreshment’.

The marketing of music as ‘nostalgic’ was a common feature of the time and signalled one way in which musical representations could be heard as a kind of prescribed memory trip. I’ll say more about this in my upcoming post on holiday records, of which Faith’s LP is an example.

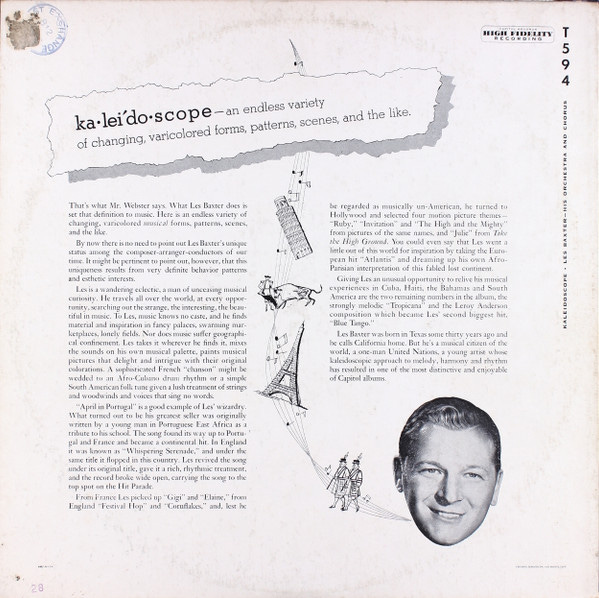

Another aspect to note from the liner notes to Faith’s LP is how he, as bandleader, is cast as uniquely gifted to bring the diversity of the world’s music to the understanding of a less-travelled audience. A similar process is at work in the liner notes to the 1955 Les Baxter album Kaleidoscope, which collected the original hit version of ‘April in Portugal’ for the first time onto a LP. The text glosses the song’s biography in such a way to suggest that, prior to Baxter’s rescue, its survival was almost accidental.

What turned out to be his greatest seller was originally written by a young man in Portuguese East Africa [a reference to Ferrão’s military career] as a tribute to his school. The song found its way to Portugal and France and became a continental hit. In England it was known as “Whispering Serenade,” and under the same title it flopped in this country. Les revived the song under its original title, gave it a rich, rhythmic treatment, and the record broke wide open, carrying the song to the top spot on the Hit Parade.

Baxter is also praised for his eclectic taste and his cosmopolitanism:

Les is a wandering eclectic, a man of unceasing musical curiosity. he travels all over the world, at every opportunity, searching out the strange, the interesting, the beautiful in music … Les takes it wherever he finds it, mixes the sounds on his own musical palette, paints musical pictures that delight and intrigue with their original colorations.

Myth relies on some connection to reality. Amidst the fairly typical hyperbole, then, we find untruths (Baxter was not an experienced traveller and apparently never left North America), half-truths (Chappell had recognised the hit potential of ‘April in Portugal’ before Baxter’s recording) and reasonably accurate information (Baxter did indeed adapt his myriad influences to his own style, making for a certain uniformity to his music, or an artistic vision, depending on one’s view). Accuracy, as ever, is one of the first things to be sacrificed on the altar of hype.

We can witness a similar process at work with the release, in 1959, of German bandleader Bert Kaempfert’s album April in Portugal, the liner notes of which proclaimed:

This album comprises a collection of some of the most popular and delightful music of and about Portugal … authentically interpreted in the lush orchestral style of Bert Kaempfert and his orchestra.

To the encyclopedist Portugal is a republic in the south-west part of the Iberian peninsula – the world’s largest producer of cork; according to the travel bureaus, it’s a tourist mecca; to the Portuguese themselves, its home sweet home.

Songwriters, on the other hand, like to expound on the traffic-stopping appeal of The Petticoats of Portugal. They find special appeal in Les Lavandieres Du Portugal (Washerwomen of Portugal), and the elegant Fadistas (men-about-town). In essence this sparkling collection magnificently captures the flavor of April in Portugal.

It’s difficult to recognise the authenticity of which these notes speak, given the distance between the sound of Portuguese music and what Kaempfert offers. As with most Kaempfert albums, it’s easy to connect the melodies to their well-known vocal or instrumental originals, yet the similarity of style removes rather than revives the original texts and contexts (a process amplified on this album by the prominent use of Spanish guitar and castanets, providing a sonic dislocation to a non-Portuguese ‘Latin-ness’). The liner notes, meanwhile, read as though someone with little or no experience of Portugal has written them. Reference to ‘the encyclopedist’ may be a rhetorical device, but it also suggests that the writer has merely gone to an encyclopaedia for information. This experience of the world from a distance would appear to be connected to the aims of the music, with listeners being invited to ‘close your eyes and listen’, suggesting that the journey to be taken is virtual.

Kaempfert, an exponent of mood music and easy listening, sits in a different camp to exotica artists like Baxter, Denny and Lyman. Fellow orchestrators George Melachrino and Geoff Love recorded versions of ‘April in Portugal’. Melachrino was an artist associated with mood music due to a series of albums designed with specific functions in mind, including Music for Dining, Music for Reading, Music for Courage and Confidence, Music for Daydreaming and Music for the Nostalgic Traveler.

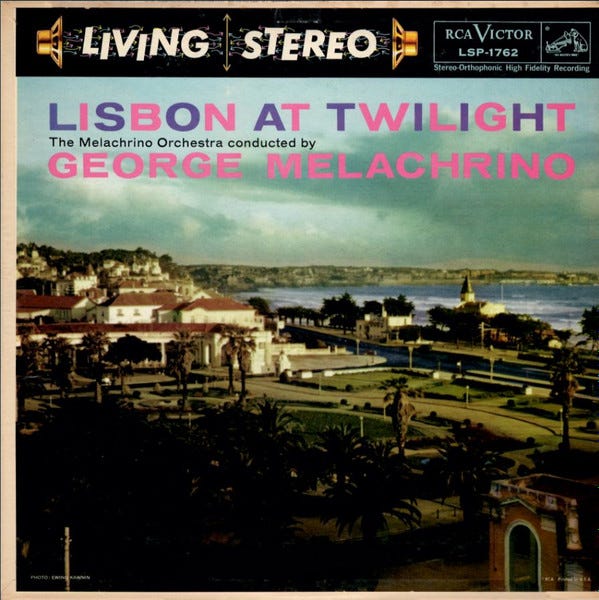

Like many other bandleaders, Melachrino released a version of ‘April in Portugal’ in 1953. He returned to the tune on Lisbon at Twilight, a 1958 album which contained twelve instrumentals based on Portuguese themes and arrangements of fados. Intriguingly, the album also featured the Portuguese guitarist Raul Nery, a composer in his own right and an accompanist to many major fado singers such as Amália. Nery, who flew to London to record with Melachrino’s orchestra, contributes two compositions to the album, and provides guitarra accompaniment (and solo lead) to all the tunes, including ‘April in Portugal’.

The liner notes to the album, which describe fado as ‘nostalgic little ballads telling of death, disappointment, drownings, stabbings and general heartbreak’, give an accurate enough account of fado practice (addressed to an American audience, despite the album’s UK provenance) before observing that Melachrino’s record will cost ‘approximately $450 less than the round-trip economy-class air fare between New York and Lisbon’.

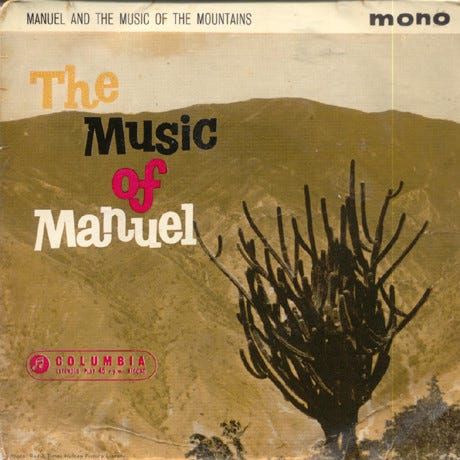

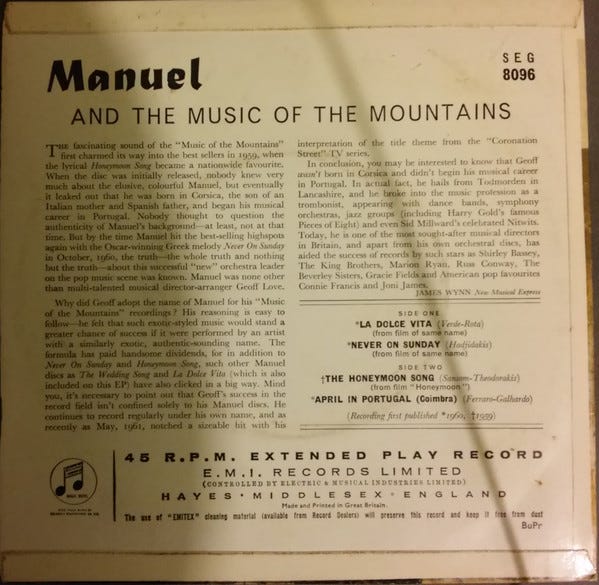

The version of ‘April in Portugal’ that appeared on the first album by Manuel and the Music of the Mountains in 1960 could not make such claims to authentic fado practice. However, like Les Baxter’s version, it provided a prominent role to an unidentified string instrument, providing a gesture towards fado.

If there was deception here, it lay in the character of Manuel himself. When the group scored its first hit in 1959 with ‘Honeymoon Song’, a story circulated that the mysterious Manuel was the Corsican-born son of an Italian mother and Spanish father and had begun his career in Portugal. In fact, Manuel was soon unmasked as none other than Geoff Love, the Todmorden-born, UK-based bandleader who was simultaneously enjoying success with lush arrangements of film and television themes. The story appeared on the back of a 1961 EP featuring ‘April in Portugal’, where the author explained that Love ‘felt that such exotic-styled music would stand a greater chance of success if it were performed by an artist with a similarly exotic, authentic-sounding name’.

As with Kaempfert, it’s difficult to gauge quite what Manuel was being authentic to. The cover of the EP, for example, depicted cacti growing in a desert, with mountains in the background, while Manuel’s name could equally reference the Iberian Peninsula or Latin America. While a later album liner might claim that Manuel’s first recording was ‘evocative of all that was Mexican’, the tendency for his records to depict various tropical scenes (sparkling coasts, waterfalls, carnival processions), combined with musical selections from around the globe, suggests that the authenticity being aimed for was mainly a general ‘foreign-ness’ imbued with exotic undertones. The album Blue Waters put it well when it declared:

Everything is here for the would-be adventurer in sound. Time and distance are no object. A warm clear mountain stream; a vast expanse of unblemished blueness above; and the subtle hint of a breeze. The music of Manuel is working.

The Nostalgia Gap

If there’s a representational slippage between actual and virtual tourism, between places and the representation of places and between vacations and their evocation, so there is a gap between described nostalgia and prescribed nostalgia. It’s as if nostalgia is something pre-programmed into us and available by affective triggers other than those of directly lived personal experience. Put another way, nostalgia plays on experience, the kind of recognised ‘universal’ experiences we can all tap into, even if we have to then map them onto personal experience.

There’s also a slippage that takes place between the associations conjured by music, memory and place. Melachrino’s Lisbon at Twilight pairs twilight with reflection, while all versions of ‘April in Portugal’ arguably tap into a chain that connects April to romantic reflection, to remembered Springs, to Paris, to love and to a fixed perfect moment. This was one reason Jimmy Kennedy had been loath to write a song called ‘April in Portugal’, feeling it would be compared with the already famous ‘April in Paris’. Perhaps he needn’t have worried, because this association was likely a major factor in his song’s success.

Besides widening the gap between the original musical representation of a city and its object of nostalgic desire, one effect of the multiple derivations of ‘April in Portugal’ was to render versions of the original Ferrão/Galhardo song into authentic fados due to their proximity to source. Thus, the semi-ethnomusicological record label Monitor (later to come under the administration of the Smithsonian Institute alongside the more famous Folkways) could release a series of fado and folk music albums in the 1960s with titles like April in Portugal, Holiday in Portugal and Lisboa Antiga.

‘April in Portugal’ and ‘Lisboa Antiga’ would become staples on the kind of holiday records I’ll write about next time around. I’ll venture beyond Portuguese-themed songs and there will be many ports to call at. I hope to see you on board.

Playlist

For anyone wishing to follow up on the versions of ‘April in Portugal’ that I wrote about here but didn’t link to, here’s a YouTube playlist that gathers several of them.

The information in this essay is adapted from a 2014 article I wrote for Volume!, the French popular music journal. Its title was ‘“Time and Distance Are No Object”: Holiday Records, Representation and the Nostalgia Gap’. I’ll be adapting the material on holiday records for a subsequent Substack essay. One of the things I enjoy about doing these song itineraries is that they’re never complete. There are always new versions to discover, new points to plot on the journeys that songs take. It was only after publishing the article in Volume! that I was made aware of the use of the ‘April in Portugal’ melody in ‘Ae Dil Mujhe Bata De’. And it was only while working on this post that I found about about Yvette Giraud’s Japanese language songs. I’ve also discovered and corrected some errors I made in the 2014 article.

Fascinating article and questions you raise, Richard. I walked into the article ignorant of the music, but found your article fascinating. You also raise some good points and interesting questions about places, tourism, and authenticity. I wonder if it's somewhat similar to seeing tribal art in a gallery or museum? One can be transported into the dimly lit Rockefeller Room at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in NYC, which houses hundreds, if not thousands, of Pacific Islander art pieces, especially Papua New Guinea. This setting and environment make the viewer feel intimidated and overwhelmed as we are surrounded by these significantly powerful objects. However, because they are stripped of their surroundings and context, and we view them from Western norms and culture, they lose their power and become subjects for Western eyes to romanticize and even fetishize.

Very different from what you pose in your post regarding the "would be Adventurer," they need not leave their home as they can experience Portugal from their living room in Topeka, Kansas.

Yet, in some respects, the museum exhibitions are similar.

I always walk away from your articles feeling educated and introduced to new thoughts and ideas, and they leave me with many open-ended questions. Thank you!