In the beginning there were objects in process and processes which relied on objects. At least that’s how I like to think about it. Especially when people tell me I have to choose between objects and processes. Or when I read ‘The world is made up of subjects, not objects’.1 Or when I’m told that music is a process, not a thing. Or that I should think about a world without objects, a world that is all about verbing and becoming (so no ‘in the beginning’ either), not a world that, nounlike, just is.

I think what many writers mean when they make statements like these is that they’re suspicious of objects thought of as ‘passive props’ (to use James Bridle’s term). Fair enough. So am I. But those of us who are interested in objects enough to write about them at length probably already feel that objects are not passive props, that they are vibrant matter with some kind of agency or capacity for evolution.

The kind of texts where I read these statements are ones I’m often sympathetic to. They speak a language I’m drawn to. I just want to get rid of their binary ‘ors’ and ‘nots’, replace them with ‘ands’: the world is made up of objects which are also subjects; music is a process and a thing; the world is a thing in a state of becoming.

I suppose I want to have my cake and eat it too.

When I find myself thinking about these things (and processes), there are all manner of artists, thinkers, poets and musicians I turn to for inspiration. I like to look for links between them. I enjoy looking for patterns and connections.

Instead of thinking of objects as ‘passive’, I might be inspired to think of them as ‘at rest’. Pablo Neruda could help me here:

It is useful at certain hours of the day and night to look closely at the world of objects at rest: wheels that have crossed long, dusty spaces with their huge vegetal and mineral burdens, bags of coal from the coal bins, barrels, baskets, handles, and hafts in a carpenter’s tool chest. From them flow the contacts of man with the earth, like an object lesson for all troubled lyricists. The used surfaces of things, the wear that hands have given to things, the air, tragic at times, pathetic at others, of such things—all lend a curious attractiveness to reality that we should not underestimate.2

From them flow … There’s that vibrant matter. And it must be at least implicit here that things wear (out) hands as much as hands wear (out) things. Humans and their tools become assemblages. Things are momentarily at rest but have worked, have worn, have been worn and used, have borne and witnessed.

Instead of worrying about nouns and verbs and objects and processes, I might turn to Timothy Morton. As a proponent of object-oriented ontology (OOO) and speculative realism, Morton has felt the need to set up defences against those who wish to do away with object-thinking. In a book review from a decade ago that struck a few notes with me, Morton summarised one line of attack: ‘If you are into objects, you are into objectification’. A bad thing. Morton wanted to trouble the binary, as did Steven Shaviro, the author whose book Morton was reviewing. In Being Ecological (2018), Morton identifies a mode of thinking that places verbs as ‘good’ and nouns as ‘bad’ and connects this to the contrast between writing and speech interrogated by Jacques Derrida. For Morton, ‘Object-oriented ontology is a way of thinking that wants to re-confuse us, much like deconstruction, about the status that we take for granted’.3

In recent months, when I’ve wanted to think about images that offer an ambiguous materiality, or that offer a delicious weirdness to the visual realm, I’ve frequently turned to Remedios Varo. Varo was not an artist whose work I knew until a few years ago. When I encountered it, I was immediately struck by its uncanny, dreamlike imagery, paintings that seemed both ancient and modern, of the real world and of imagined times and places: sensual, saturated, magic realist.

Predating all these figures for me, somewhere nearer the beginning, there was Björk. The Icelandic singer has been a thread running through my listening life, from the noisy fun of the Sugarcubes in the 1980s to the ever-morphing personas and concepts of her solo work.

Still now, when I want to encounter songs about objects and processes, song-objects in process and art worlds being ecological, I’ll go back to Björk.

Pablo Neruda. Timothy Morton. Remedios Varo. Björk Guðmundsdóttir. Four minds out there in a random cosmos, connected by a fifth: mine. What makes me want to link them? I’ve said before that I both seek and follow connections. Is it the remnant of a childhood desire for everyone and everything to get along, for no one and nothing to be left out of place? I’ve lived enough life now to know that can’t happen, that there’s as much division and distinction as there is connection and reconciliation. I know it’s okay to let things be, to not force them together.

And yet I want to. I’d be untrue to myself if I didn’t nurture my personal ecology, to see which strands affect which. The connections that follow are those that keep Björk at the centre because she is a beacon for my project. It would be interesting to follow potential connections between the others (Morton and Neruda via the figure of William Blake, for example, or Neruda and Varo as exemplars of distinct artistic camps in Latin America), but I’m not pursuing those here.

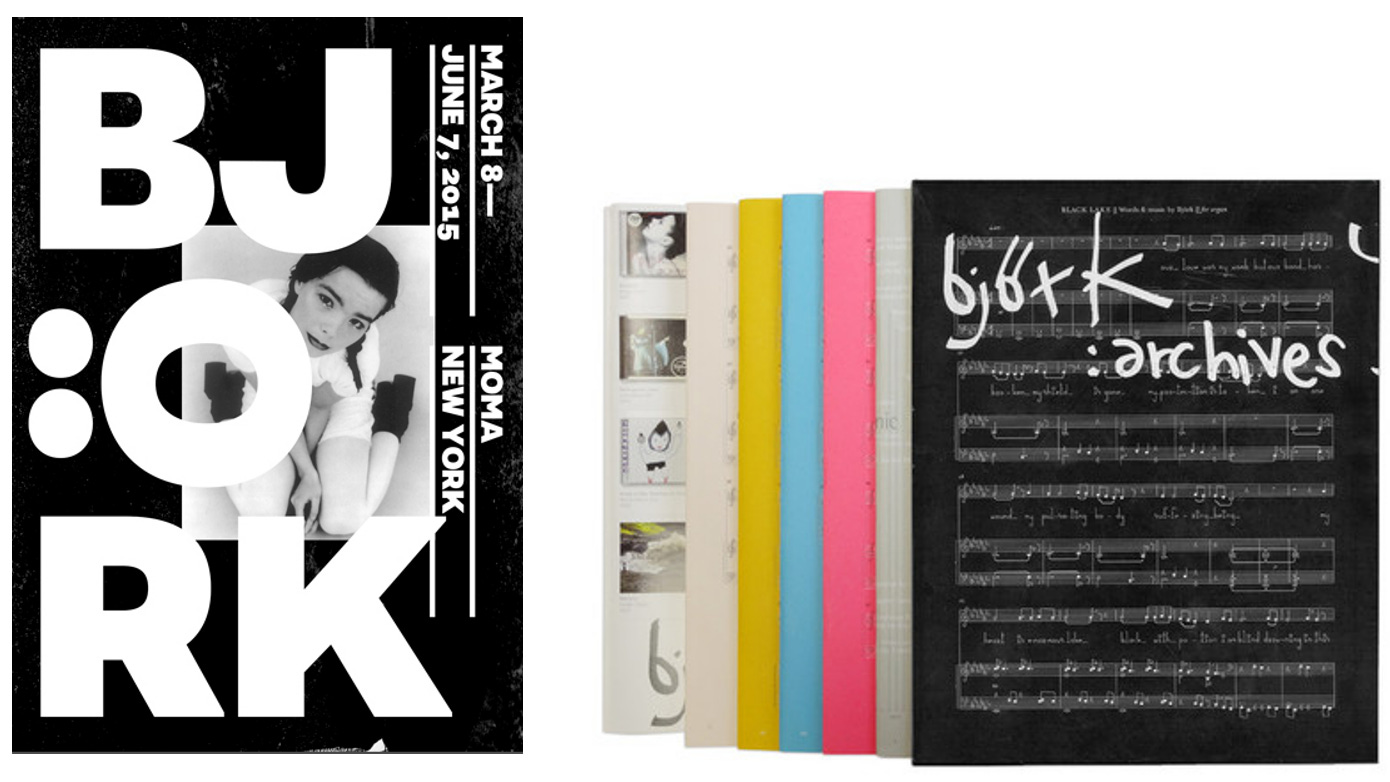

Björk and Morton are the easiest to connect because of references they’ve made to each other’s work and a collaboration from a decade ago. In 2015, New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) put on the exhibition Björk, a sort of mid-career retrospective with some suggestions of future directions the artist might take. The exhibition was criticised in some quarters for not doing justice to the range of Björk’s artistic vision and for rendering her dynamic processual methodologies in ways that were too static: a focus on objects over processes, in other words.

Not having attended the show, I can’t speak for its effectiveness, though I’m aware from visits to other sites of the challenges in rendering music-based and multimedia work in exhibition spaces. The MoMA event did, however, lead to the creation of an object which has been useful to my project: the fascinating box of booklets that is Björk: Archives.

This box of inspiring texts became a useful reference point as I started to write about songs and objects in earnest. It contains the following documents:

Introduction, by Klaus Biesenbach. Biesenbach became Chief Curator at Large at MoMA in 2010 and was the organiser of the Björk exhibition. He summarises the musician’s career and how it might be represented in a museum space.

Beyond Delta: The Many Streams of Björk, by Alex Ross. Ross is a music critic for The New Yorker and author of The Rest Is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century (2007) and Listen to This (2011). An admirer of his books, I was interested to read how he situated Björk’s music in the broad sweep of modern music across genre and style.

Björk Creating: Myths of Creativity and Creation, by Nicola Dibben. Dibben is Professor of Music at the University of Sheffield. As a fellow music academic, I’ve met Nikki a few times and seen her present her work at conferences and symposia. Her book on Björk is excellent, and her related research led to contributions to the Biophilia app (discussed below). For the Archives box, Dibben provides a scholarly account of nature, technology and creation in Björk’s work.

This Huge Sunlit Abyss from the Future Right There Next to You, by Björk Guðmundsdóttir and Timothy Morton. Morton is Rita Shea Guffey Professor of English at Rice University and, as I mentioned above, a writer associated with the object-oriented ontology (OOO) school of thought. This part of the Archives box reproduces a series of emails between Morton and Björk, who includes in her invitation to collaborate a line which has since become an endorsement on at least one of Morton’s subsequent books: ‘i have been reading your books for a while and i like them a lot’.

The Triumphs of a Heart: A Psychographic Journey Through the First Seven Albums of Björk, by Sjón. Sjón is the pen name of Sigurjón Birgir Sigurðsson, an Icelandic author of poems, novels, lyrics and screenplays. He has known Björk since they were teenagers and has co-written several songs with her. For Archives, he wrote a long poem that traces Björk’s life and work by mapping it onto various landscapes and natural phenomena. The largest booklet of the five, it is illustrated with artwork from Björk’s albums, videos and installations.

The dust jacket of the first booklet is covered in an ingeniously designed timeline of the artist’s life, while the other four have fold-out jackets containing musical notation and lyrics for songs (‘Pagan Poetry’, ‘All Is Full of Love’, ‘Aurora’ and ‘Cover Me’; notation for another song, ‘Black Lake’, adorns the box itself). The other object in the box is a double-sided sheet of stickers based on the covers of singles, albums and DVDs.

I find it a playful and thought-provoking collection of items to interact with. Some of the contents inform what follows.

Björk’s music sheds light on my three main areas of interest regarding the materiality of song in that her songs are about objects and the fascinating relationship between them; they are also beautiful, intricate, strange, shape-shifting objects; and they are presented as part of a broader technological ecosystem that challenges the ways we’ve traditionally thought songs should exist in the world, how they are mediated, what relationship they have with other material objects and media platforms.

Morton touches on this in the 2017 book Humankind: Solidarity with Nonhuman People:

Ideas aren’t colorless and flavorless. They have a specific frequency, a specific smell, they have ways of being thought … [Björk’s] song “Hyperballad” is a classic example: she shows you the wiring under the board of an emotion, the way a straightforward thing like “I love you” isn’t straightforward at all. So don’t write a love song like that; write one that says you’re sitting on top of this cliff, and that you’re dropping bits and pieces of the edge like car parts, bottles and cutlery, all kinds of not-you human prosthetic bits …4

This accords with my own feelings about ‘Hyperballad’ and about other songs whose lyrics highlight our interactions with the object world. But Morton also picks up on my other interest, which is songs themselves as objects:

My favorite version of “Hyperballad” is the Subtle Abuse mix, a twelve-inch remix, the expanded spectral dance version that has much more in it than just it, taking little bits of it and making thousands of copies of them, as if a whole were actually a bagful of eyes that on closer inspection were also bagsful of eyes …

Twelve-inch remixes are neither copies nor separate things, but spectral bags full of eyes that haunt the seemingly individual house of a song. The DJ never weaves the twelve-inch vinyl discs into a seamless whole that’s bigger than them. She weaves a whole lot of partial objects, eyeball bags into a large eyeball bag. A string of Pandora’s jars adding up to one Pandora’s jar, not one to rule them all, but a pretty good place for a night out.

When Björk asks you to remix her song she sends you all the parts, all the sound files, and says have at it. Do anything. Chop it into little pieces and multiply the pieces and rearrange them. Make more out of this than the whole that I made. Show me the wiring under the board of my showing people the wiring under the board.5

I’m reminded here of a line from Baby Dee’s song ‘Safe inside the Day’: ‘a gift that’s bigger than the box it came in’. For me, that describes what a song can be. And Björk has given us many of those gifts.

A third aspect of my songs and objects project is the role of the songholder. As I wrote in my first ever Substack post,

To a certain extent, human songholders can be thought of as tradition bearers, those who take song up, maintain it and pass it on. My use of the deliberately artificial-sounding ‘songholder’, however, is a way of connecting what humans do with song to what machines and other nonhumans enable songs to do. I also like the resonance with words like ‘torchbearer’, ‘keyholder’ and ‘skyscraper’. These words can be thought of as modern versions of kennings, figurative devices used in Old Norse and Old English poetry and also found in Icelandic poetry. Examples abound in classic texts such as Beowulf and in the work of the Viking skald (poet) Egill Skallagrímsson, who uses the wonderful term ‘song weigher’ in his poem ‘Sonatorrek’.

Björk exemplifies the songholder not only in her twenty-first century continuation of what generations of skalds did before her, but also in her interactions with the nonhuman songholders of nature and technology.

The biographical poem that Sjón contributes to Björk: Archives picks up on similar themes, mixing fairy tale, mythology and musical appreciation. It presents Björk as contained in something larger than herself but also as a container for other things, including of course her songs. In the poem, Björk is part of a constellation or ecosystem.

Klaus Biesenbach takes a similar, if less mythopoetical, approach in his appraisal of the artist:

All of a sudden it becomes clear that for all of her career Björk has created a body of work that could be described within the theory of Object-Oriented Ontology, in which the landscape around her, she herself, and the landscape inside of her—her blood, her organs, the sounds made by her and perceived by her—are all one universe of objects and subjects, subjects and objects, robots and humans, plants and animals, stone and volcanoes and oceans at the same time.6

I agree with this observation, which is why Björk is one of the people I always return to when I’m thinking about the relationship between things and processes. Examples can be found across her career. Many of my favourites come from the 2011 album Biophilia, which was the most recent at the time of the MoMA exhibition and Sjón’s psychographic poem.

The example I’ve used most when I’ve given talks on this topic or when I’ve taught my ‘Case Studies in 21st Century’ course at Newcastle University is ‘Virus’. Sjón’s lyrics for the song describe a viral longing or starvation, the desire to join, to spread, to be hosted. This happens through natural and human-made objects: the virus that needs a body, the soft tissue feeding on blood, the mushroom on the tree trunk, the ‘flame that seeks explosives’.

Both Nicola Dibben and Alex Ross highlight the way that the music subdivides and proliferates on ‘Virus’. Ross writes about this in his contribution to the Archives project. Dibben’s analysis comes bundled with the Biophilia app, a technical innovation designed for the then-new iPad, and also downloadable at the time to iPhones. This provided an unusual case of musical exegesis accompanying the musical object at the moment of its release.

The Biophilia app encouraged the idea of getting inside songs, of songs as journeys through space, songs as constellations and as objects in wider constellations. The user would enter via a constellation interface made of song titles. Once chosen, each song ‘star’ would open to reveal description and analysis of the song, differently designed scores, games and animations.

One of the interactive possibilities in the app for ‘Virus’ is to prevent or delay Björk’s voice from continuing the song by swiping the green viruses away from the pink cells. If no virus is present, the music continues on a loop. Once the viruses are allowed to surround the cell, the vocal resumes. In this way, you have to accept the idea of song as virus if you wish to hear the track as written. You have to let the song in.

Here’s app designer Scott Snibbe demonstrating the ‘Virus’ game (including a later part which I haven’t explained above), with an initial summary from Björk:

The stems of Biophilia’s songs were offered for remixing and to educate schoolchildren in music theory. Like the protein that transmutates in ‘Virus’ and like what Timothy Morton says about the remixes of ‘Hyperballad’, Björk’s songs provide compelling studies of the possibility for transmutation to be thematised in song and practised in the evolution of the song object.

Thirteen of the many remixes of Biophilia’s songs were collected on the 2012 album Bastards. The album opens with Omar Souleyman’s take on ‘Crystalline’, one of my all-time favourite remixes. I find the way Souleyman’s C21 variant of dabke melds with Björk’s hymn to crystal growth beguiling and addictive. The Bastards sleeve doesn’t credit other musicians for this track, but my guess is that the all-important keyboards are courtesy of long-time Souleyman collaborator Rizan Said. These added musical elements do to the song what the song describes crystals doing: growing, multiplying, creating new formations. Remix time and geological time may differ, but we’re offered a reminder that all matter is mutating, whether at a speed we can detect or not.

Growth and mutation are key themes of Biophilia, whether in the cellular incursions of ‘Virus’, the multidirectional accumulations of ‘Crystalline’ or the shifting tectonics of ‘Mutual Core’. These songs all rely heavily on metaphor, often connecting biological and geological processes for human behaviours and relationships: ‘I knock on your skin and I am in’ (‘Virus’); ‘we mimic the openness of the ones we love’ (‘Crystalline’); ‘if things were done your way / my Eurasian plate subsumed’ (‘Mutual Core’).

The cover of Bastards is a still from Andrew Thomas Huang’s video for ‘Mutual Core’: Björk as shifting geological strata.

The over of Bastards collages the stratified singer with shots of the Icelandic landscape. I find myself back in the world hymned by Sjón in his psycho(geo)graphic poem. And I’m reminded that what songwriters, singers and songs are doing is bearing witness to the objects of the world, the way they’re arranged, how they sit in landscapes, the relationship they have with each other, how they affect each other.

Sjón’s poem casts Björk as a kind of naïve witness: ‘at all hours nature staged its spectacle for the girl and found its existence confirmed / in her senses’; ‘she was there as nature’s participating audience / its witness’.7

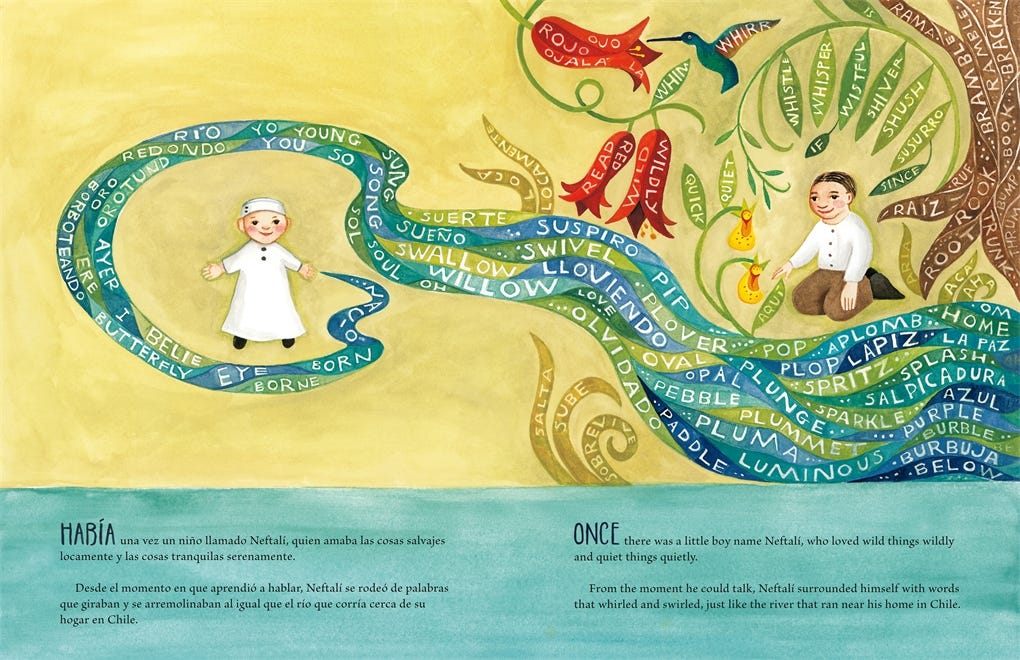

That’s where Neruda comes back in for me. I’d already identified Neruda as a beacon poet for my project with his geological-anthropological questions— ‘Stone within stone, and man, where was he?’8—and his ‘elemental odes’ to the artichoke, the atom, numbers, the Earth and its minerals, wine, his suit, the seagull, maize, bees and bicycles. But I hadn’t thought of comparing Neruda to Björk until I read about Monica Brown and Julie Paschkis’ book Pablo Neruda: Poet of the People in Maria Popova’s ever-inspiring newsletter The Marginalian.

Once I’d got a copy of the book, I was struck by the parallels with Sjón’s The Triumphs of a Heart: a similar way of writing a human life ecologically, a child growing up in nature in a magical and secluded part of the world, at one with the landscape. Of the many wonders of Julie Paschkis’ illustrations, perhaps the most notable are the words flowing through the landscape, as if tree trunks and rivers contained the language humans need to name them. That bond between word and thing is crucial to Neruda’s poetry as it is to Björk’s songs and the ways Sjón, Brown and Paschkis evoke them.

The style of the books matches the desire to evoke a child’s perception of the world. Brown and Paschkis’ is a children’s book; Sjón’s is written as though it were. Björk in interview often presents perspectives that channel a surprise and curiosity about the world that many of us lose after childhood. Neruda, too, was able to hold on to something that had taken root in him as the boy Neftalí Reyes.

In the words of Ilan Stavans, Neruda found the ode ‘the finest way to sing of common things’.9

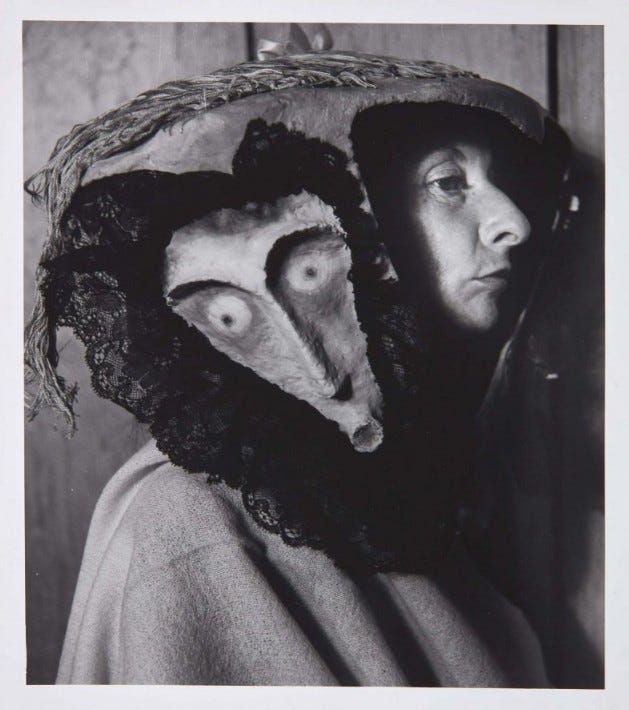

I mentioned another figure earlier, the Spanish-Mexican painter Remedios Varo (1908-1963). Her paintings offer a surreal vision of the interconnectedness of humans and nonhumans, objects and subjects, the Earth and the cosmos. When I became familiar with them, I often found myself thinking of Björk. I even started imagining some of Björk’s famous costumes and masks as emanating from Varo’s paintings. Having made the connection in my head, I was delighted to read that Björk is an admirer of Varo and Leonora Carrington (another artist who moved from her home country to contribute to the surrealist movement in Mexico City) and that she has a Varo print on the wall of her kitchen in Reykjavik.

I connected Varo to Björk for the reasons I’ve mentioned, but it’s also important to me that Varo repeatedly turned to music as an inspiration for her work. There are many examples I could turn to, but I’ll choose the 1956 painting Armonía (Harmony).

Here’s what Varo had to say about the picture:

The character is trying to find the invisible thread that unites all things, that’s why he’s stringing together, on a musical staff of metal threads, all kinds of objects, from the simplest to a scrap of paper containing a mathematical formula, which is in itself already a great jumble of things. After he manages to put the different objects in their place, by blowing through the clef that holds up the musical staff, a music should emerge that is not only harmonious but also objective, that is, able to move the things that surround him if that’s how he wishes to use it. The figure peeling away from the wall and collaborating with him represents chance (which so often intervenes in all discoveries), but objective chance. When I use the word objective, I understand it to be something outside our world, or rather, beyond it, and which finds itself connected to the world of causes, and not of phenomena, which is our own.10

Causality and phenomena. Those sound like concepts the OOO philosophers like to talk about, but I won’t go further into that here. What I will say is that this universe of things that move or are moved by music that is objective (in Varo’s sense of the term) and harmonious seems to resonate with the Björkian use of things that I’ve been harping on about.

As Lara Balikei puts it in an exhibition catalogue for the Art Institute of Chicago’s Remedios Varo: Science Fictions, ‘Varo made the otherwise invisible perceptible to sight, giving symbolic form to chance, objectivity, and the threads that connect the universe’.11 Balikei highlights the at-least dual aspect of the treble clef on the table next to the composer: ‘not just a facet of musical notation … but also a wind instrument consisting of one continuous metal tube’ (p. 55). Varo’s description of the painting draws attention to the clef as instrument, too, one capable of moving objects within the immediate physical space (and perhaps beyond?). There is a play here, perhaps, on music’s noted capacity to move its listeners. Music has an agency that goes beyond the alteration of the air.

Varo’s weird instrument calls to my mind those deployed by Björk on Biophilia—pendulum harp, sharpsichord, gameleste—and which can be seen in Louise Hooper’s 2013 documentary When Björk Met Attenborough.

As I was writing these paragraphs, it occurred to me that this autumn will mark thirty years since I travelled to Chile to spend a year in South America. One of the first things my hosts in Santiago did was to arrange a visit to Pablo Neruda’s house at Isla Negra, where we perused the poet’s collections of objects—ships’ figureheads, model boats, ships in bottles, shells, bottles, pipes—and listened to the roar of the waves on the rocky Pacific coast. That memory sent me to the attic to dig out photos of the trip; such is the way for a mind always wishing to make tangible connections.

Shortly after that visit, I made the journey south to the city of Concepción, where I would be based on and off for a year. While there, I was given a book containing Neruda’s Veinte poemas de amor y una canción desesperada and Cien sonetos de amor by a charming, earnest young man with whom I enjoyed many conversations. It has been living on my bookshelves ever since I returned to England. Opening it now, I find a bookmark inside, a ‘Recuerdo de Chile’ featuring a gilded and embossed flat-capped Neruda beaming encouragement.

I also find a marker on the page containing the forty-eighth love sonnet. I’m not sure who marked the page, my romantic young friend or romantic young me, but I take it as a sign to read. The poem is about ‘two happy lovers’ who ‘make one bread’, who ‘cast two shadows that flow together’, who hold the day ‘not with ropes but with an aroma’, who ‘did not shatter words; their happiness is a transparent tower’.12 Accompanied by the air and wine, ‘the night delights them with its joyous petals’:

Two happy lovers, without an ending, with no death, they are born, they die, many times while they live: they have the eternal life of the Natural.

Surrendering to this memory, I’m once again grateful that, in the end as in the beginning, there are subjects and objects and things and processes and art that helps us join them all together. And, though I’ve taken time to follow my footsteps, I also know that the connections that exist in this text are the tracks of a human life, not something generated in seconds by a prompt fed into a machine. I remain in it for the slog, not the slop.

Thank you for slogging along with me.

That line comes from James Bridle’s Ways of Being: Animals, Plants, Machines: The Search for a Planetary Intelligence. I like this book a lot and feel it will inspire future directions on my Songs and Objects project. But I don’t feel you can just say there are not objects in the world when millions of language users and object users have decided over thousands of years that there are.

Pablo Neruda, ‘Towards an Impure Poetry’, quoted in The Poetry of Pablo Neruda, ed. Ilan Stavans (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2005), xxxiii.

Timothy Morton, ‘Rock Your World (Or, Theory Class Needs an Upgrade)’, The Los Angeles Review of Books, 28 July 2015; Timothy Morton, Being Ecological (Pelican, 2018), 145-7.

Timothy Morton, Humankind: Solidarity with Nonhuman People (Verso, 2017), 114-5.

Morton, Humankind, 115.

Klaus Biesenbach, ‘Introduction’, in Björk: Archives (Thames & Hudson, 2015), 7.

Sjón, Triumphs of a Heart: A Psychographic Journey Through the First Seven Albums of Björk, in Björk: Archives (Thames & Hudson, 2015), np.

Pablo Neruda, ‘The Heights of Macchu Picchu’, translated by Nathanial Tarn, in The Poetry of Pablo Neruda, 160.

Ilan Stavans, ‘Introduction’, The Poetry of Pablo Neruda, xxxiv.

Remedios Varo, ‘Harmony (Armonía), 1956’, in On Homo Rodans and Other Writings, edited and translated by Margaret Carson (Wakefield Press, 2024), 142.

Lara Balikei, ‘Armonía (Harmony)’, in Remedios Varo: Science Fictions, ed. Caitlin Haskell and Tere Areq (The Art Institute of Chicago, 2023, 54. I regret that the Varo exhibition began just days after my visit to the Art Institute in July 2023. A missed connection.

I’m using Stephen Tapscott’s translation of ‘XLVIII’ from Cien sonetos de amor in The Poetry of Pablo Neruda, 518-9.

Bjork's music is so emotional, dramatic, and theatrical. Seeing the videos and watching the app tutorial, "Biophilia" couldn't be a more apt title. I suspect that when one is from a place that is literally growing and changing daily, their connection to the land is profoundly deep and meaningful.

I also loved seeing Varo and one of her paintings make an appearance! And your photos of how Neruda embellished his landscape with objects couldn't be a more apt way to conclude your piece.

Landscapes, objects, art, music, literature, and the human connection with it all run deep throughout all of your examples.

Thanks for taking us on your narrative journey, Richard!