Notes on Guy Clark

Old No. 1 is fifty.

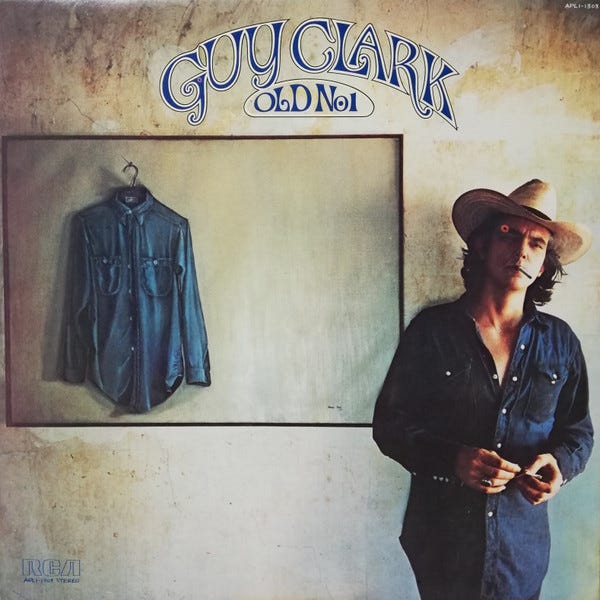

November 1975. RCA releases Old No. 1, the debut album by Guy Clark. It’s the result of over a decade’s worth of songwriting, touring, getting a record deal, refusing the arrangements the label’s preferred producer wanted to impose, going back to demos with producer Neil Wilburn, adding singers (Rodney Crowell, Emmylou Harris, Steve Earle), deciding on acceptable compromises.

Clark is thirty-four when Old No. 1 comes out. Born 6 November 1941, a date I might not have recorded here were it not for the fact that, as I write this, it’s 6 November 2025. Next May will be a decade since he died.

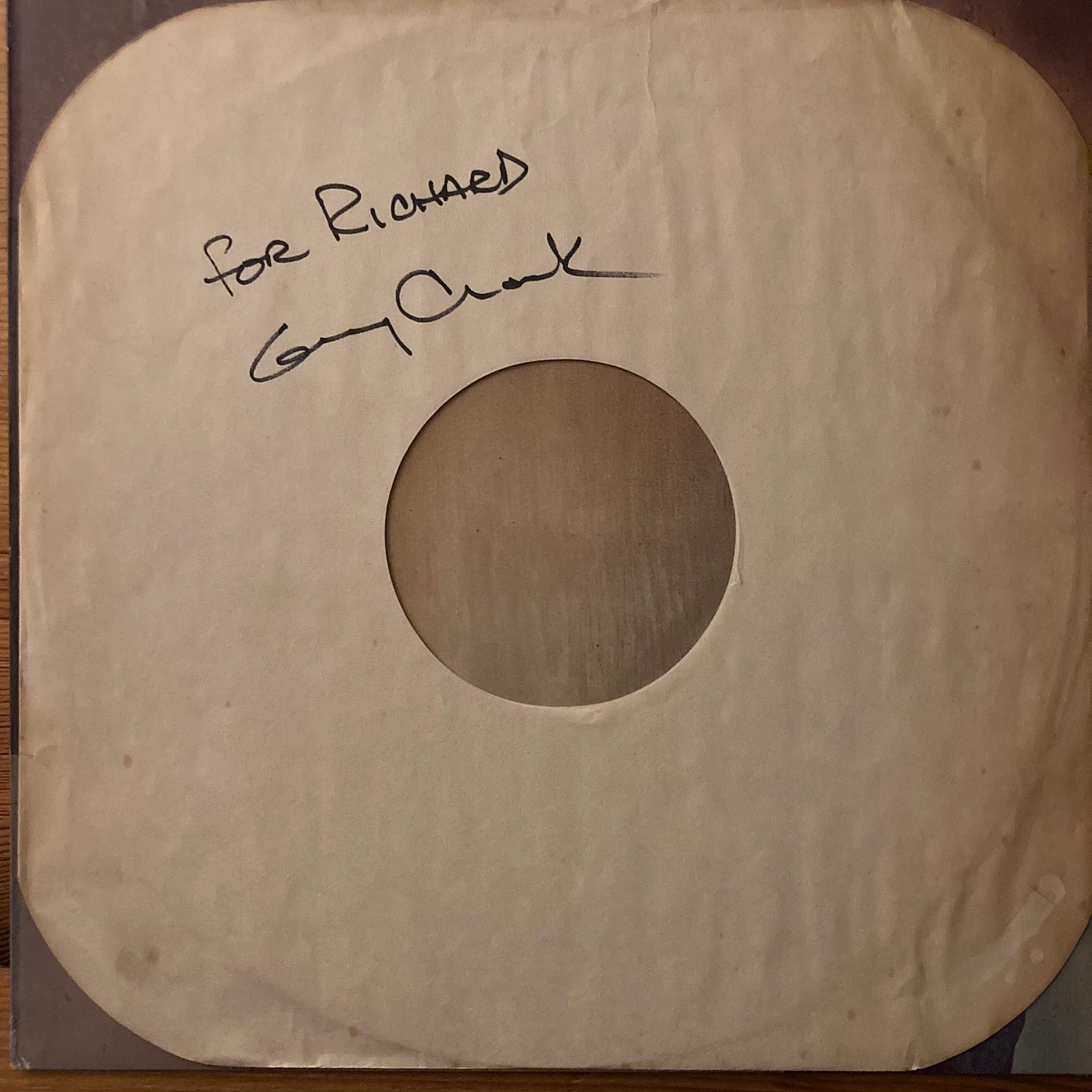

March 1990. I’m eighteen. I sit with friends and family to watch Robert Earl Keen and Guy Clark play sets in the Plough & Harrow pub in Newton Abbot, Devon. Keen’s West Textures has recently been released in the UK and become a fixture on my turntable. Clark has moved from being a name I occasionally stumbled across in record guides and music history zines to the artist behind Old No. 1, an album I acquire via the 1988 Edsel reissue. That album will never be far from my mind. Nor will this evening. Even then, we knew how unusual it was to have such artists visit our small town in the southwest of England. That wonder will only grow with the years, making this a treasured memory. I get a few photographs, none of them brilliant quality, and an autograph.

Years pass. I always intend to write something about Old No. 1. I come close on occasion, then put the notes aside for another time. I lose so many thoughts and notes on the album and on Guy Clark’s wider importance to me and others. I come to terms with that.

November 2025. The album’s fiftieth anniversary. I decide to publish some of the notes that remain. I start to think that fragments are a truer way of expressing what Clark’s songs mean to me than the kind of longer-form essay I’d previously imagined. It’s not like I’m looking to close anything down here. Nothing definitive, always something left open.

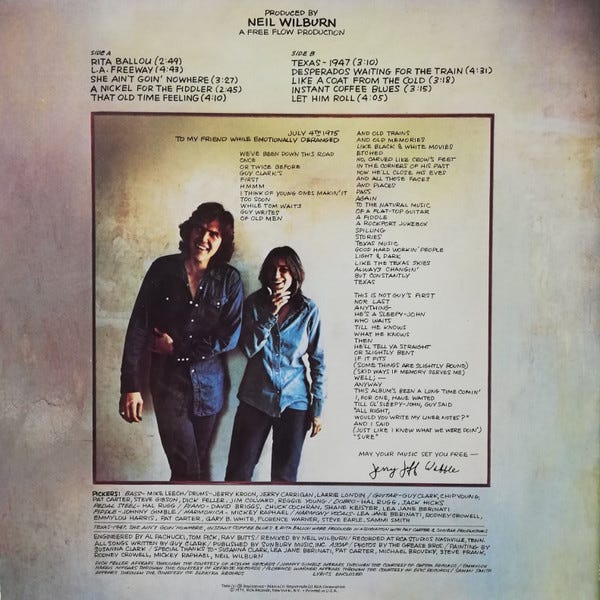

The cover of Old No. 1. Denim, material, objects. Guy’s and Susanna’s smiles. A moment of forever. Jerry Jeff Walker’s liner note, that same mixture of factual and fanciful you’d find on other country endorsements of the time (Kris Kristofferson on Mickey Newbury’s Looks Like Rain, Johnny Cash on Kristofferson’s Me and Bobby McGee). Also, for me, the Edsel logo on the rear cover of the reissue. Such an important imprint for me at that time, a portal to areas of music history I might not have discovered in those pre-internet days. Old No. 1 was ED285. Other reissues from 1988: The Notorious Byrd Brothers (ED262); Gene Clark with the Gosdin Brothers (ED263); Tim Rose’s Morning Dew (ED267); Loudon Wainwright’s Attempted Mustache (ED269); Alexander Spence’s Oar (ED282); Guy Clark’s Texas Cookin’ (ED287); Kaleidoscope’s A Beacon from Mars (ED288); John Cale’s Vintage Violence (ED230). We still ordered record label catalogues in those days.

‘L.A. Freeway’ is the song I always expect to open Old No. 1, even after all these years and all these plays. It takes less than a second to remind me the opener is ‘Rita Ballou’, for which I’m always glad: a great start to an album. I suppose that ‘L.A. Freeway’ was the magnet that pulled me in and never let me go. That guitar hook. That bittersweet lyrical thread that runs from ‘pack up all your dishes’ to ‘don’t you think it’s time we’re leavin’’. A song where the determination to leave has its confidence belied by the ache of the music and the sense that the singer’s partner still needs persuading: ‘Oh, Susanna, don’t you cry, babe / Love’s a gift that’s surely handmade / We got somethin’ to believe in’. And, though Clark’s default would be to play it solo or with minimal accompaniment, I wouldn’t be without the other textures on the album version: Johnny Gimble’s fiddle, Mickey Raphael’s harmonica, the additional voices on the chorus. The instrumental outro stretches the song to nearly five minutes; I could lie in that bed of sound for much longer.

Clark mentions in interviews that ‘L.A. Freeway’ began life as a thought in the back of a car. The exact words change with each retelling, but are always based around what would become the song’s refrain: ‘If I can just get off of this L.A. Freeway, without getting killed or caught’. He holds on to the fragment for two years, letting the song grow in its own time. The lyrics turn again to fragments in other people’s projects: Without Getting Killed or Caught as the title for Tamara Saviano’s Clark biography and the documentary that follows (directed by Saviano and Paul Whitfield); Truly Handmade as the title for a posthumously released collection of acoustic demos. A reminder that song objects have their own biographies.1

‘We got something to believe in’. As good a line as any for a piece on Guy Clark or Heartworn Highways. Or Townes Van Zandt, Steve Earle, Larry Jon Wilson, David Allan Coe. For a long time, I wanted to write about the sense of familiarity I felt with these artists: hearing their music, reading about them, seeing them in Heartworn Highways. I first saw the film on British TV in the early 1990s, videoed it, played it back. Around 2003-4, I bought the DVD, watching it repeatedly in my room on Gallowgate during my first year and a half in Newcastle. It became something I’d put on like a record, something to comfort and reassure me. A coat from the cold. Something to believe in.

‘Texas—1947’. The train rendered in exquisite detail, but also the flattened coin. How the train imprints itself on the memory of the bystanders, while the six-year-old boy is smart enough and quick enough to get the memory stamped in nickel. The whole story recalled from decades later. Does he still have the coin?

Old No. 1’s cast of characters: Rita Ballou, the ‘walkin’ talkin’ Texas texture’; the ‘fiddler from Kentucky who swears he’s 83’; the old people of ‘That Old Time Feeling’—the salesman, the bluestime picker, the soldier, the lover; the old people of ‘Texas—1947’—old man Wileman, old Jack Kittrell; the old men playing dominoes in ‘Desperados Waiting for the Train’; ‘the lady beside me’ in ‘Like a Coat from the Cold’; the grown men and women of ‘Let Him Roll’—the tried and true wino; Alice, with a black veil covering her silver hair; the couple from the mission singing ‘Amazing Grace’; old one-eyed Jack. The folk of indeterminate age: the one-night-standers trying to feel fully dressed the next morning in ‘Instant Coffee Blues’; the hitchhiker ‘standin’ on the gone side of leavin’ in ‘She Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere’.

Johnny Gimble’s fiddle on ‘A Nickel for the Fiddler’. And how this song initiates future Clark songs: ‘Virginia’s Real’ on Texas Cookin’; ‘Sis Draper’ on Cold Dog Soup.

Gimble’s appearance on Old No. 1 was enough for me to pick up a double album of his. The Texas Fiddle Collection, CMH Records, 1982. I bought it in the early 1990s on one of my occasional culture-hunting trips to London. Rhythm Records in Camden, where I’d make a beeline after the record shops on Oxford Street and Tottenham Court Road and before heading to Compendium Books. Rhythm had so many hard-to-find treasures: soul gems, psyche reissues, Butch Hancock cassettes. I got my copy of Townes’ Live at the Old Quarter, Houston, Texas there; it still has the shop’s discreet sticker on the back.

The opening credits to Heartworn Highways. Guy’s hypnotic guitar figure for ‘L.A. Freeway’. The dedication to Skinny Dennis in both the film credits and Clark’s lyric. The shots of the artists—somehow, there’s always one I’ve forgotten since the last time I watched. Clark’s photo coming to life in time with the song.

The same song is later used for the opening credits of Without Getting Killed or Caught.

‘Desperados Waiting for the Train’. A song so good, no one can get its title correct. Sometimes it’s ‘desperadoes’, sometimes ‘waitin’’, sometimes ‘a Train’. A song packed with biographemes: playing ‘Red River Valley’ in the kitchen; the old man running his fingers through seventy years of living; dominos in the Green Frog Café; tobacco-stained chins. I didn’t need to know what ‘Moon & 42’ meant to be put square in the picture. ‘Like some old Western movie’ indeed.2

Freaky apple pie. Ice cream on a stick. Homegrown tomatoes. Fairs, festivals, barbecues. The evocation of the sensual.

It makes sense that ‘Let Him Roll’ and ‘Randall Knife’ should share a guitar figure. Two songs with a death at their centre, both concerned with what people leave behind. Personal effects. How to grieve in song.

‘Life’s a tune you whistle in the dark’. A line in ‘Bag of Bones’, from 2002’s The Dark. Another song to ignite my fascination with life writing and objects. A fascination Clark had too, if his lyrics are anything to go by (and they are). Bodies as objects with a complex relationship to age. Bodies as reminders of earlier incarnations.

The song as object, something to be crafted, sculpted, stored, retrieved. A trace left behind, from a life and for the benefit of other lives.

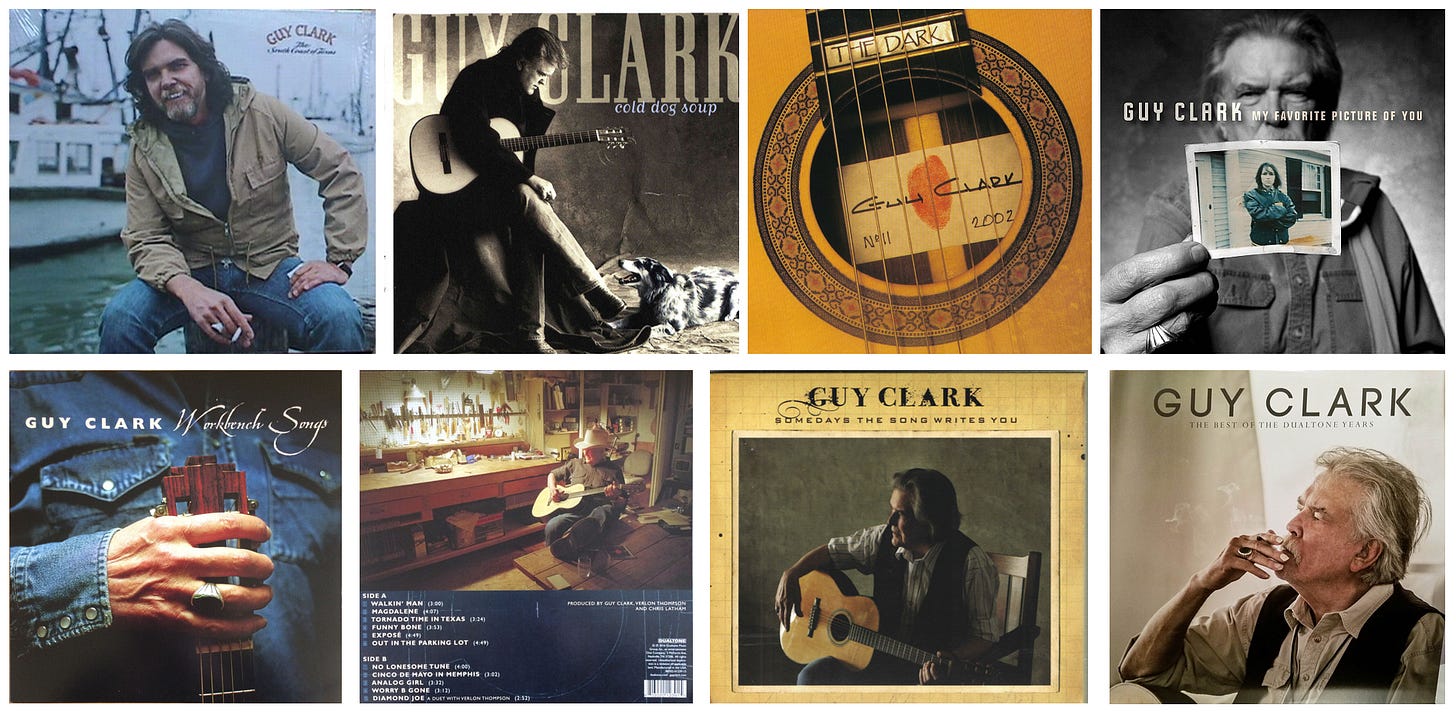

Visual imagery was always important. There are examples on all the albums, from the denim shirts of Old No 1 to the photograph on My Favorite Picture of You. Susanna Clark’s vital role, as artist and photographic subject. (And not forgetting her covers for Willie’s Stardust. and Emmylou’s Quarter Moon in a Ten Cent Town) The persistence of cigarettes across the discography. The chunky ring that appears whether Clark is holding a cigarette or a guitar. The thumb print on the cover of The Dark that serves as a trace of the body, evidence, seal of authenticity, identity. (The songs as evidence of lives lived, confessions). The CD booklet for The Dark uses the by-then common image of Clark as craftsman: wood shivers, basement workshop, customised guitar. The photos are by Jim McGuire (credited as ‘Senor McGuire’). Those are McGuire’s photos on the front and back of Old No. 1 too (credited to The Grease Brothers, his photography studio). McGuire’s Nashville Portraits is one of my favourite books of music photography. ‘The camera loves you, and so do I … click’.

There’s something to say about work: many of Clark’s songs are about the doing or the consequences or the memory or the lack of work: ‘Desperados’, ‘Boats to Build’, ‘Homeless’, ‘Immigrant Eyes’, ‘South Coast of Texas’. Also, the work of poetry: ‘Cold Dog Soup’.

Listening to Guy’s songs taught me that it was okay to write about the specific—things that you know about—and have it apply universally. When he tells you about Monahans in Texas-1947, that could be a similar experience anywhere in the world. You can write to the small picture and ir becomes the big picture. That’s how I learned about songs, just listening to songwriters like Guy.

—Lyle Lovett3

Clark’s songs mix time, age and experience, the texture of history and biography, the objects we live by and with, what is wrought upon our bodies and minds by time and the past.

Geographies of the imagination: ‘L.A. Freeway’ then and now and all the roads in between. Not so long ago, I found myself on a long southbound stretch of the A1, stuck in slow moving traffic, listening to Old No. 1 and really feeling that song, singing along, willing escape from the gridlock.

‘How she hangs that music in the air’ (‘Virginia’s Real’, on Texas Cookin’). A square dance painted in words and music. Multisensory country sublime.

‘Instant Coffee Blues’. Trying to make it rhyme: country grammar, southern phonemes, Texas textures. Then later, on ‘Homeless’ or ‘The Dark’, the realisation that the ends of days and lives don’t always rhyme.

Textures of the voice. Clark’s alternation of deep grain with high lonesome and yodelling registers.

Textures of the body, repeated gestures. Running your hands through years of living. Time, age, experience.

Rhythm: train songs, the rhythm of words and music. Narrative, storytelling, imagery, like some old western, characters and caricatures.

He didn’t like the ‘craftsman’ label that was put on him. He wanted to be thought of as a poet like his friend Townes.

There’s a 1988 interview with Townes Van Zandt and Guy Clark, part of a broadcast for KPFK-FM Folkscene that has appeared on various unofficial releases. Both artists have revealing and contrasting things to say about songwriting, craft, collaboration and whether the song exists for the songwriter or for others. Van Zandt says that he doesn’t think of writing a song for other people to sing; he implies that the song exists for itself. Clark points out that lots of writers in Nashville make their living writing songs for others which they have no intention of performing themselves. He then contrasts that with his own view: he writes songs to have things to perform. He says he wouldn’t be able to perform without his repertoire of songs. Might this be one of the reasons Clark disliked the ‘craftsman’ tag, that it placed too much emphasis on the song object at the expense of performance?

Tamara Saviano thinks that Clark’s alternative vocation as a luthier contributed strongly to people’s desire to label him as a craftsman (in contrast to, say. Leonard Cohen, another songwriter known for painstaking work on lyrics but who tends to be thought of as a poet). It may also have annoyed him that people referred to his friend Townes Van Zandt as the poet. There could be more than one, couldn’t there?

John Spong on the ‘songwriting as craft’ issue as it played out in Van Zandt and Clark:

Townes’ [songs] sounded almost metaphysical, like he’d plucked them off the air after they’d floated in through an open window, as he often claimed. Guy’s were stark and grounded, like he’d found them in the back of a roughneck’s pickup in the Monahans oil field.4

But note also JT Van Zandt’s insistence on his father’s work ethic when it came to crafting songs. He contradicts this a little in an interview cited by Saviano, where he claims that Clark had the stronger work ethic of the two. But the point is well made that the TVC-poet/GC-craftsman binary requires nuance.

“Keepers” was Clark’s phrase for songs that are worth recording. Like a fisherman, he implies, you hook and reel in a lot of songs from the subconscious but most of them are too scrawny and ill-shapen to take home. So you throw them back into the pond with instructions to eat a lot of plankton and fill out.

—Geoffrey Himes5

He didn’t need to be topical, and so the songs didn’t need to be finished quickly.

My least favourite of his songs are those too prosaically connected to events in his life. Evidence for the prosecution: the song he and Terry Allen wrote about his dog getting shot. Songs like ‘Desperados’ escape this danger, steeped as they are in everyday mythologies and ordinary affects. The ‘sumbitch’ landlord in ‘L.A. Freeway’ and the ‘S.O.B.’ shooter in ‘Queenie’s Song’ feel qualitatively different to me in terms of lyrical affect.

I’m always happy when other writers evoke objects and materiality when discussing Clark.

Holly Gleason:

There was the ashtray: a circle of skulls, often overflowing with the charred and twisted papers, hand stuffed with tobacco or otherwise. Everyone who wrote with Guy Clark knows it, a resonant artifact that spoke to life’s inherent earthiness.6

John Spong:

The rest of the room is cluttered with the ephemera of his life, some of it stored in little clementine orange crates, the remainder hanging on the walls and scattered on tables. Guy is endlessly loyal, and each item carries a specific sentimental tie. There’s a tight portrait of Van Zandt taken by their friend Jim McGuire. A cane that artist Terry Allen found for him in Santa Fe. Every last piece of a fiddle that Guy smashed on a mantel in a drunken fit forty years ago and still means to repair. And on a stand-up table along the back wall, the actual Randall knife, along with others sent in by fans and a letter of thanks signed by the knife maker himself.7

Craig Clifford and Craig Hillis use the term ‘ruthlessly poetic’ to describe a school of Texas singer-songwriters that include Clark, Van Zandt and several others. Acknowledging the strangeness of the term, they note that ‘it is, in writing as in songwriting, the unexpected but mysteriously telling phrase that lets us see something from a perspective that we wouldn’t ordinarily have access to’. What is ‘mysteriously telling’ about this particular phrase? One answer seems to be the dedication to purpose, such that Van Zandt ‘lived for the sole purpose of writing profound songs’. The authors attend to the issue of reading biography for clues to songcraft rather than reading biography into song content: ‘Is it really a matter of the purity of artistic intent of these ruthlessly poetic songwriters, or is it the ruthlessly poetic nature of the songs that we care about?’.8

Saviano’s biography is well-written and answers a lot of the questions I had about Guy Clark. At the same time, there were times I felt that my admiration fade. It was as if I needed the mystery to still be attached to the songs rather than to know that their writer was someone who, from a young age, was expert at many things and probably could have been a success in several fields. It’s odd because I’ve long thought of him as a craftsman (and there’s so much supporting material for that characterisation), but reading about his approach to doing things approached the banal at times. Does this provide an answer to why I’ve repeatedly slid away from trying to write about those country artists who made such an impression on me as a young man?

‘Hillbilly haiku’: the term Clark uses in ‘Cold Dog Soup’ to describe Townes Van Zandt’s songs. An apt description of the craft and labour of songwriting to which both artists adhered.

He takes influence from Japanese painting and negative space. ‘It’s what you leave out, so you focus on the important part rather than the clutter’.9

One of his early songs is ‘Step Inside This House’. A life sketched in objects: a picture on a wall, a book of poems, a prism glass, a guitar, a pair of boots, a yellow vest, a leather jacket and bag. He’s not happy with it. Too wordy. He doesn’t release it. When Lyle Lovett records the song as the title number of a 1998 covers album, Clark wishes he’d edit out the clutter. His own recording surfaces posthumously on Truly Handmade.

Clark’s use of imagery, especially that associated with paintings, photographs and films, comes through strongly in the interviews and reviews gathered in Saviano’s book. Barry Poss of Sugar Hill Records: ‘He creates these little intimate, personal narratives that speak to a larger landscape. He may be writing about a knife or a boat or a dance or a road or a hooker or even a tomato, but they’re also about the human condition and all its complexities and flaws’ (p. 210). Verlon Thompson, longtime Clark collaborator: ‘What impresses me is the way he uses fewer words to give you more images. With two or three words, you get a complete visual idea in your head about the character and the setting and what’s going on … One of the songs that I think illustrates that is ‘The Last Gunfighter Ballad’ … a three-minute movie’ (p. 192). Vince Gill: ‘The visual side of those songs [is] what annihilate[s] me’ (p. 192). Joe Ely describes hearing a Guy Clark song as ‘just like seeing a great movie’ (p. 228).

Some critics found Clark’s imagery to be clichéd, simplistic or sentimental. John Rockwell, writing for the New York Times in 1976, near the start of Clark’s solo career, uses the word ‘maudlin’: ‘an old gunfighter as a symbol of an anachronistic American spirit; the freeway as alienation; a prostitute showing up at the funeral of the man she once loved and shedding a tear’.10 Jon Pareles, reviewing a 1990 show by Clark, Townes Van Zandt and Robert Earl Keen for the same publication, notes a tendency for Clark’s songs to ‘slip into easy sentimentality and clichés (a caged bird, ties that bind) as they unequivocally praise the country over the city, friendship over alienation and the good old days over the present’. He finds Clark’s representation of women simplistic: ‘saints who would save a troubled man (“like a coat from the cold”) or whores who won’t’.11

Nanci Griffith on ‘She Ain’t Goin’ Nowhere’:

It’s always been my favourite song of Guy’s. It felt like it was my life story the first time I heard it. You know, Guy writes like Larry McMurtry, the novelist, he’s extraordinary at writing a woman’s feelings, finding that place in a woman’s heart.

After talking with a woman who runs a women’s shelter in Australia for which Clark’s ‘Better Days’ has become the theme song, he rewrites a line that he’s always found too lightweight (the one line the women in the shelter didn’t like either). The new version is recorded for Keepers and he makes sure Roseanne Cash includes the new lyric when she covers the song for This One’s for Him. Details matter to him.

I recall listening to This One’s for Him, the tribute album celebrating Clark’s 70th birthday, on a long coach journey in 2012. Standouts then and now:

Willie Nelson, ‘Desperadoes Waiting for a Train’ [sic]. The ideal voice to put to this song. For me, so much more affecting than The Highwaymen’s multi-voiced version.

Emmylou Harris & John Prine, ‘Magnolia Wind’. Sounding like a John Prine song: something about the clipped economy of the lyrics. These two voices together and Jen Gunderman’s accordion.

Terri Hendrix, ‘The Dark’. Hendrix gets to the dark wonder of it.

Patty Griffin, ‘The Cape’. This could have sat easily on her brilliant contemporaneous album American Kid.

Kris Kristofferson, ‘Hemingway’s Whiskey’. Like Nelson, better on his own when covering Clark than with the Highwaymen. Again, an ideal voice-song match.

Jack Ingram, ‘Stuff that Works’. Doing his mentor proud on this perfectly pitched version of one of my favourite mid-career Clark songs.

Jerry Jeff Walker, ‘My Favorite Picture of You’. A new song to me when I heard JJW’s version (it would appear as the title track of Clark’s final studio album in 2013). A very Walkeresque song; I almost mistook it for an original at the time.

That I could go in listing is testament to the excellence of the musicians on the tribute and, of course, to the sturdiness of the material. Songs made of stuff that works.

It strikes me again that Guy Clark and others (Townes Van Zandt most obviously) were for me and a few of my friends something like what the people Clark sings about were for him. People who taught us how to do and think about things. And, just as Clark wondered why his mentor in ‘Desperados’ was ‘all dressed up like those old men’, we wondered why these songwriters weren’t marked out from the crowd. Discovering Townes standing in a car park outside a York pub ahead of a show one afternoon in 1994 and thinking: how can all these people just be walking by?

Vince Gill’s ‘Nothin’ Like a Guy Clark Song’ underlines the object-oriented nature of Clark’s songwriting. A list song made up of fragments of Clark lyrics and borrowing the guitar figure that Clark used for ‘Let Him Roll’ and ‘Randall Knife’; that musical figure becomes an evocative object in itself.

As Sherry Turkle notes, some objects are life companions.12 The Randall knife is a companion object and also the object that connects son to father. The ‘coat from the cold’ is a reliable object (an example of ‘stuff that works’), but is also a simile for a life partner. ‘Old friends shine like diamonds’.

The immortal lines from ‘Dublin Blues’:

I have been to Fort Worth, and I have been to Spain And I have been too proud to come in out of the rain And I have seen a David, I’ve seen a Mona Lisa too And I have heard Doc Watson play “Columbus Stockade Blues”

It’s not just the cultural levelling of the lyrics, it’s the ‘hmm-hmm’ after ‘Fort Worth’ and ‘David’. I was glad to hear Joe Ely retain those vital non-lexical rhymes in the version he recorded for the tribute album.

‘He didn’t know he couldn’t fly, and so he did’. (‘The Cape’)

The crackle on my copy of Old No. 1. Surprised I never bought a second vinyl copy. (I have two copies of the 1978 album Guy Clark for some reason). I suppose I’ve had the twofer CD of Old No. 1 and Texas Cookin’ for about as long as I’ve owned a CD player and there’s the crackle-free digital version that’s never off my car’s music system (how many journeys have been soundtracked by Guy Clark?). Even so, another vinyl purchase might be on the cards.

If I do get another copy, I’ll need to remember to transfer the inner sleeve from my old one.

Tamara Saviano, Without Getting Killed or Caught: The Life and Music of Guy Clark (Texas A & M University Press, 2016).

I know that Moon and Forty-Two are domino games, and I’ve read the rules, but I didn’t know back then and we didn’t have the internet.

Lyle Lovett, Foreword to Nick Evans and Jeff Horne, Songbuilder: The Life and Music of Guy Clark (Amber Waves, 1998), 9.

John Spong, ‘Guy Clark: One Last Look’, Texas Monthly (May 2016), https://www.texasmonthly.com/the-culture/guy-clark-one-last-look/ (accessed 26 May 2018).

Geoffrey Himes, ‘Remembering Guy Clark, The Craftsman’, Paste (May 2016), https://www.pastemagazine.com/article/remembering-guy-clark-the-craftsman.

Holly Gleason, liner notes to Guy Clark, The Dualtone Years (LP, Dualtone, 2017).

John Spong, ‘He Ain’t Going Nowhere’, Texas Monthly (January 2014), https://www.texasmonthly.com/articles/he-aint-going-nowhere/ (accessed 26 May 2018).

Craig Clifford and Craig D. Hillis, eds, Pickers and Poets: The Ruthlessly Poetic Singer-Songwriters of Texas (Texas A & M University Press, 2016), 1-3.

Guy Clark, in Kathleen Hudson, Telling Stories, Writing Songs: An Album of Texas Songwriters (University of Texas Press, 2001), 63.

John Rockwell, ‘Guy Clark Is Singing Progressive Country’, New York Times (9 December 1976): 60.

Jon Pareles, ‘Sung Tales About Just Plain Folk’, New York Times (11 November 1990): 67.

Sherry Turkle, ed., Evocative Objects: Things We Think With (MIT Press, 2007).

Wonderful love letter to an old friend that has clearly inspired you for decades.

And, I am with you on the old Edsel (as well as other labels, including some of the original bootleg labels like Psycho and Eva). Back then, before the internet, Spotify, and Discogs, this is how we discovered these albums. And, I, too, first heard "Beacon" via Edsel (but have since found an original copy).

PS, have you heard the Euphoria record ("A Gift From Euphoria")? It's an album that I think you might really like (very eclectic and musically all over the place, but quite special and nothing quite like it then, or now).

Now, now Richard. 'Queenie's Song' is a lovely piece!

I remember The Plough and Harrow gig still. How weird to see Guy (and Robert) at the top of Buckland estate, in tiny non-descript Newton Abbot!

'Better Days' lyric - what was the rewrite?

Robert Forster: 'Wonderin' who sounds better in the dark / is it Townes Van Zandt / or is it Guy Clark?'

Great stuff, Richard. Keep it coming.