As a teenager I would spend a lot of my free time at a secondhand record stall in the indoor market at Newton Abbot, the Devon market town where I grew up. The stall was run by a man named Robin who, when he wasn’t selling records, worked for the AA (the British motoring organisation and breakdown recovery service).

During the years I frequented Robin’s stall most regularly (the mid to late 1980s), I was moving from the heavy metal and hard rock I’d got into in my mid-teens to the proggier and/or hippier end of the spectrum, a move that Robin seemed keen to encourage. He’d pull out records by the Grateful Dead, Camel, ELP, Van der Graaf Generator, Henry Cow and others, and he would make recommendations.

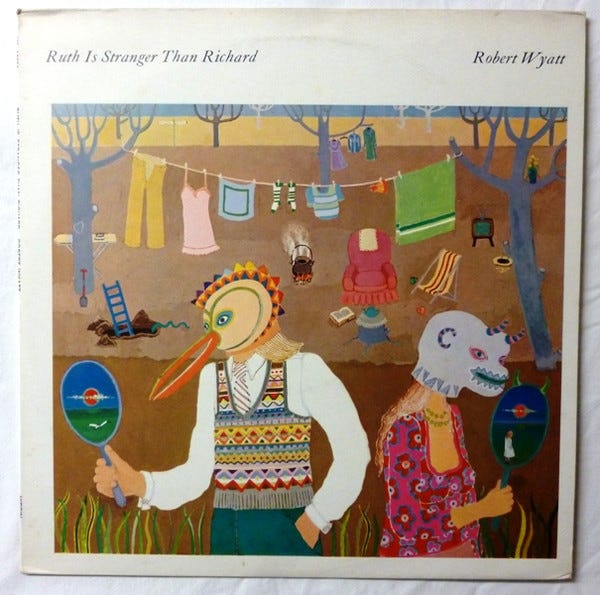

One day he suggested I try a record by Robert Wyatt called Ruth is Stranger than Richard.1 I was struck by the title and the cover, which showed two humans wearing nonhuman heads: one an exotic, long-beaked bird, the other a short-horned creature with a mysterious mouth hinting at fearsome jaws.

I didn’t buy the album that day. Another record took my fancy, though I can’t recall which one now or whether it’s something I still have. I do currently own two copies of Ruth is Stranger than Richard, one on CD and one on vinyl, which I picked up many years later, never quite having forgotten Robin’s initial recommendation. And I still find that cover fascinating, seeing it now as a classic example of Alfreda ‘Alfie’ Benge’s work. Alfie is Wyatt’s wife and the subject and co-creator of many of his songs. She’s also quite clearly, once one gets to know more about the couple, the blonde woman wearing the animal skull cap in the painting, with Robert Wyatt the tank-top wearing human beneath the bird mask.2

The mysteries of the human-animal world, as well as Benge’s influence on Wyatt and his work, are central to the album I want to focus on here. Rock Bottom came out the year before Ruth Is Stranger than Richard, and 26 July 2024 marks its fiftieth anniversary.

I wasn’t completely unaware of Robert Wyatt prior to Robin’s recommendation. As a keen chart watcher in the early 1980s, I’d been bewitched by Wyatt’s version of Elvis Costello’s ‘Shipbuilding’ when it was rereleased in 1983 and entered the UK charts. I recall seeing the video for the single and Wyatt’s performance on BBC’s Whistle Test.

It wouldn’t be until the late 1990s, however, when I really fell for Robert Wyatt’s music. This was helped by the release in 1997 of a new studio album, Shleep, which garnered considerable press attention. The album appeared on the Rykodisc-affiliated label Hannibal, which also reissued the majority of Wyatt’s solo albums the following year and the brilliant EPs box set in 1999. All of this conspired to send me on a Robert Wyatt deep dive, a term which seems apt when paired with Alfie Benge’s new artwork for the Rock Bottom reissue (shown below [left/top] alongside Benge’s original cover for the 1974 release on Virgin Records).

Not long after this, Rock Bottom became one of my all-time favourite albums, up there with Blue and Astral Weeks and Blood on the Tracks and Nina Simone and Piano! and Flyin’ Shoes and Old No. 1 and all my other all-time favourites.

There are many things I continue to love about this album, from its dreamy watery soundworld (a perfect accompaniment to the lyrics) through its use of nonsense and whimsy to the way it thematises domestic life and relationships through references to human relationships with the nonhuman world.

Although he had been a member of the 1960s group The Wilde Flowers, Wyatt first came to wider attention as a drummer, singer and composer in the jazz-rock group Soft Machine, with whom he appeared on four acclaimed albums. In 1971, by which time he had already released his first solo album The End of an Ear, Wyatt found himself at odds with the other Softs and, following a period of increasing acrimony, was forced out by the other members. He formed Matching Mole (a play on the French for ‘Soft Machine’) and released two albums with them in 1972 (Matching Mole and Little Red Record) before disbanding.

In 1973 Wyatt broke his back in a fall and began using a wheelchair, ending his career as a drummer. Rock Bottom, the first album released after his life-changing accident, was really the start of his solo career, one which was nevertheless filled with creative collaborators. The albums and EPs that were released over the next four decades saw Wyatt switching instruments to the keyboard (and occasional trumpet) and focussing more on singing. While still often drawing on jazz and experimental music, and engaging in lengthy instrumental sections, Wyatt started working in more explicitly song-like forms to a greater extent than he had in his earlier work. Even so, his love of sonic experimentation—which had become apparent with the avant-garde sound collages of The End of an Ear and the second Matching Mole album—suggested that he was unwilling to give himself over completely to song.

In contrast to those singer-songwriters for whom music was seen as a relatively unimportant backdrop to the delivery of clearly enunciated lyrics, Wyatt would tend to use words as just one element of a larger sonic palette, sometimes by the use of extended instrumental sections, at others through the distortion of the vocal itself. Because his paralysis had made touring impractical, Wyatt became known predominantly as a studio artist, meaning that he changed from being a highly energetic and visible back seat musician (as a drummer) to a more invisible front man. This lack of onstage visibility has no doubt further removed him from consideration as a singer-songwriter, where onstage visibility is often used to enhance the communicative channel between performer and audience. Working primarily in the studio also enabled, and perhaps encouraged, Wyatt to focus on sonic experimentation.

Even before this, however, Wyatt was fascinated by sound and often used the concert stage and the recording studio as laboratories for experiments into various sonic possibilities. In 1972, he told an interviewer that he considered songs he was working on as ‘props for making noises’ and the words used in them as ‘outside intelligible conversation’. The kinds of noises Wyatt has made during his career have been varied, from extending his singing via nonsense language, sound poetry, overdubbing, whistling and scatting to placing his voice(s) alongside an eclectic mix of musical instruments and studio technology. His contributions to Soft Machine included ‘A Concise British Alphabet’, in which he sang the alphabet forwards and backwards, and ‘Dada Was Here’, where he sang and scatted in Spanish. The End of an Ear was an extended experiment in sound collage, with conventional song form abandoned in favour of texture, layering and what Wyatt once called ‘an aural wildlife park’.

In the liner notes to the 1998 reissue of Rock Bottom, Wyatt writes of composing the songs in Venice, using ‘a very basic little keyboard with a particular vibrato, that shimmered like the water that surrounded us’. This keyboard, elsewhere identified by Wyatt as a Riviera toy organ, plays a vital role in creating the soundscape of Rock Bottom, a suite of songs with very personal themes that create the impression, as with much singer-songwriter material, of being ‘about’ the person who has composed and is singing them. The sense of compositional intimacy and the relationship between composer and instrument is highlighted in another comment Wyatt makes about the Riviera: ‘I was able to tune in with the kind of vibrato I wanted, and I was able to play rather like I would sing if I could be a little choir. I could set my voice right into it, and it was like stepping into a warm bath of sound. I felt really at home’. The keyboard is a crucial layer in the album’s dreamlike sonic palimpsest.

Also important to the album’s unique sound world were the use of peculiar lyrics that both harked back to a tradition of nonsense literature (from Lewis Carroll and Edward Lear to Edward Gorey and Ivor Cutler) and incorporated the private language of relationships via playful exchanges between Wyatt and Benge. This singer-songwriter ‘type’ might be described as ‘stream of consciousness’, as exemplified by Van Morrison. Comparisons have been made between Rock Bottom and Morrison’s critically revered Astral Weeks, not only in terms of shared intimacy, but also in the way that sound is used; Morrison’s album, with its mix of jazz and rock styles, was reportedly an influence on Wyatt, via Benge’s suggestion. As Wyatt’s biographer Marcus O’Dair writes, ‘Rock Bottom shared the unhurried spaciousness of Astral Weeks: the willingness, in Robert’s words, to just let things unfold’.

On the one hand Wyatt’s album could be heard as removed from the social world, with the singer addressing his partner rather than us; at the same time he seems to be inviting us, via his soundworld, into the most intimate of spaces, and we are drawn to witness as unique and affecting a world as that presented on Astral Weeks or Blue. In songs like ‘Alifib’ the use of nursery rhyme and nonsense language summons an intimacy that is enhanced by the realisation that the song is about Wyatt’s partner and that hers is the voice that can be heard responding to and reproaching him later in the song.

Before this, however, we have the first side of the album. Rock Bottom opens with ‘Sea Song’, which Wyatt describes as his ‘first love song to Alfie’. A more abstract, though no less heartfelt, love song than his earlier song ‘O Caroline’ (on the first Matching Mole album), ‘Sea Song’ is an excellent example of what might be termed Wyatt’s ‘domestic nonsense’, in that it describes his lover as ‘partly fish, partly porpoise, partly baby sperm whale’, praises her ‘terrific’ drunkenness and mourns the passing of shared wonderland nights and the emergence of a ‘different you, in the morning when it’s time to play at being humans for a while’.

There’s something wonderful about calling your partner ‘a seasonal beast’ and delighting in their metamorphosis into human-animal-fish hybrids. I adore the sublime melodies in this song and how they work with the unconventional rhymes.

You look different every time You come from the foam-crested brine It's your skin shining softly in the moonlight Partly fish, partly porpoise, partly baby sperm whale Am I yours? Are you mine to play with?

The way the ‘shining’ of the third line and the ‘mine’ of the fifth line echo the ‘time / brine’ couplet is superb, as is the way that the triple ‘partly’ of line four is picked up in the subsequent line (not shown here): ‘Joking apart …’ Later in the verse we get the quickfire ‘late at night, you’re quite alright’ followed by several words without an obvious rhyme. It seems inconsistent but holds together brilliantly, like a coral.

That wonderful, bittersweet admission that ‘I can’t understand the different you in the morning when it’s time to play at being humans for a while’, that suggestion that it’s the dream world, or the drunken, ecstatic nature-saturated world that’s the real one, not the banal world of everyday ‘reality’: that’s the essence of ‘Sea Song’ for me, and of Rock Bottom and much of Robert Wyatt’s music more generally (though not his more obviously political ‘non-misusable’ material from the following decade3).

Sea/water themes continue on Rock Bottom’s second track, ‘A Last Straw’, with its references to ‘seaweed’, ‘rocky bottom’ and the invitation ‘into the water we'll go / head over heel’. Given the romantic themes that pervade the album, that last line reads to me like a wonderful way to combine the sea imagery so dear to Wyatt and Benge with a phrase commonly used to describe falling in love: new romance as a dive into the unknown, a disorienting tumble through the water.

At 1:56, Wyatt switches from singing the discernible lyrics of the song to a series of nonsemantic ‘wah wah’ sounds, as if the tumble through the water has taken his ability to do more than gurgle. The return of the lyrics a minute later is like a brief resurfacing before words disappear from the song for good and it moves into a wash of instrumentation. Driven by Hugh Hopper’s bass, Laurie Allan’s restrained drums, and with Wyatt playing an assortment of items (as well as voice he’s credited with ‘keyboards, guitar, Delfina's wineglass’), ‘A Last Straw’ becomes a swishy but stable soundworld. A plinking series of piano keys going gradually upward and then descending provide a sense of drama and a nod perhaps to waves and the exoskeletal creatures inhabiting the rocky bottoms of the coast.

As much as the lyrics, it’s this continuous wash of music and the way the tracks swish into each other that maintains the (non)sense of the aquatic throughout the album. As ‘A Last Straw’ withdraws from earshot, in comes ‘Little Red Riding Hood Hit the Road’, its arrival marked by Mongezi Feza’s trumpet spluttering into noisy life. This is the track whose words are hardest to make out, due to a combination of gibberish (‘Orlandon't tell me, oh no / Don't say, oh good Godon't tell me’), a more subdued vocal mix and the decision to reverse the tape at one point so that the song lyrics are heard backwards. Continuing the watery theme, it’s as if Wyatt’s words are coming to us from underwater, barely discernible but still recognisably human sounds in an otherwise marine ecology. Following some equally obtuse lyrics from Scottish nonsense poet Ivor Cutler, the busy foam of ‘Little Red Riding Hood’ fades out at the send of Side A like the tide receding in the distance.

This sense of a private world with its own language—the language of relationships, with their pet names and secret codes—is even more evident on ‘Alifib/Alife’, a song-suite that comprises much of the second half of Rock Bottom. The titles are two plays on Alfie’s name and also reference the musical keys of B and E. In many ways the song’s lyrics are typical nonsense verse, with made-up sounds such as ‘no nit not’ and ‘nit nit folly bololey’ taking the place of more conventional, sensible lines. As with much nonsense verse, there is enough grammatical structure for the lines to seem ‘correct’, and a semantic logic that suggests the song could make perfect sense in a topsy-turvy world, one its listeners may have visited in dreams, or in their own relationships.

Lewis Carroll’s influence can be heard in words which morph from familiar ones to neologisms, as when Wyatt sings ‘I can’t forsake you, or forsqueak you’. The lyrics also mention characters or places which could derive from nursery rhymes or children’s literature, such as Burlybunch, the water mole, Hellyplop, fingerhole and ‘Alife my larder’.

While we only hear from Wyatt in the ‘Alifib’ section, Benge also contributes to the domestic nonsense in ‘Alife’, a response section that partially corrects Wyatt’s silliness: ‘what’s a bololey when it’s a folly? I’m not your larder, I’m your dear little dolly’. Another major voice (or pair of voices) on this track is heard with Gary Windo’s insistent bass clarinet and tenor saxophone, a reminder of the jazz and improv circles that Wyatt moved in.

‘Little Red Robin Hood Hit the Road’ does for Side B of Rock Bottom what its similarly titled track does for Side A, closing down the second group of three songs with some prime nonsense from Ivor Cutler. Prior to this, there’s a rocky (in another sense) section dominated by Mike Oldfield’s guitar, a more obvious lead voice here than Wyatt, though I always find Wyatt’s singing of the ‘In the garden of England’ verse incredibly moving. ‘Dead moles lie inside their holes / The dead-end tunnels crumble / In the rain, underfoot / Innit a shame?’: another great quickfire rhyme—rain/shame—and a sense of pathos again connected to the nonhuman world. Under the ground now rather than the sea, but a common theme of human inaccessibility: ‘can’t you see them? can’t you see them?’

On an album that has more go-to moments than I could count or name, there’s one in this final track that remains a punctum for me. It’s at 4:36, when Fred Frith’s viola, which has been a building presence in the song, comes to the fore in a passage with provides an aching, keening counterpart to Cutler’s surreal lyrics.

Then, in the album’s closing seconds, the strings distort into something akin to seagull squawks and we’re back on the shore, with a madman crying ‘hahahahaha!’

As I sit here, not far from the shore while on a visit to family in Portugal, listening to and thinking about Rock Bottom on its fiftieth birthday, I think about my own encounters with the water. I think of times I tumbled in the sea without a care, and of other times when I realised my confidence was misplaced and that the sea could snatch me away without anyone noticing. I felt that combined joy and anxiety the other day as I took my first dip of the year at Praia do Meco. The sun was baking, the sea inviting, and many others were cavorting in the waves. It was beautiful in the water but that pull was still there, that drag that is a known feature of the waters off this beach. I remembered Hart Crane’s warning in his poem ‘Voyages’: ‘there is a line / You must not cross nor ever trust beyond it / Spry cordage of your bodies to caresses / Too lichen-faithful from too wide a breast. / The bottom of the sea is cruel’.

I think that dichotomy is recognised in Rock Bottom. There is the wonder of being in a new relationship, of feeling at one with the environment, of engaging with domestic affairs and private whimsy, of getting close. And there is also a sense of dissonance and disturbance, of danger lurking under the surface, of different yous. Hitting rock bottom, after all, is not something any of us want to do.

There have been many wonderful cover versions of Wyatt’s songs from this era, especially ‘Sea Song’ and ‘Alifib’ (the two most coverable). For this post I’m going to choose one that gets to the heart of the sense of collaboration that permeates Rock Bottom and much of Wyatt’s and Benge’s other work. It’s a version of ‘Sea Song’ by Bill Callahan, Will Oldham (as Bonnie Prince Billy) and Mick Turner that first appeared as part of a series of collaborative covers instigated by Callahan and Oldham during the 2020 Covid lockdowns. These covers, which came with specially commissioned videos, were collected on the 2021 album Blind Date Party, the physical releases of which came with booklets containing additional artwork for each song. The artwork for ‘Sea Song’, by Lila and Belle Turner, also adorns the cover of the album.

When I first heard this version of ‘Sea Song’, I was thrown first by the strong contrast between Callahan’s deep tones and my memory of Wyatt’s high singing voice. At the same time, I’ve always found Callahan’s a comforting voice and its sonority seemed to match both the domestic comfort hymned in the song and the sense of reassurance many people were seeking at the time this version was released. The next thing that jolted me was the swift addition of Oldham’s voice singing in duet with Callahan. I hadn’t thought of ‘Sea Song’ as a duet, but it makes perfect sense: what might be lost in consistency of vocal register instead moves the focus to different voices working together towards some kind of harmony. When, at 4:26, Callahan sings ‘we’re not alo-o-one’, wavering very slightly on the word, he really nails this as a song about companionship. I find that deeply moving.

Mick Turner creates a wash of sound that fits well with his Dirty Three work and his solo releases while staying true to the improvisatory, exploratory soundworlds that Wyatt would immerse himself in. The tension builds throughout, especially in the second half, and there’s a real sense of the song being much bigger than the humans who populate its first part, as if the song could continue to grow and envelop those who set it in play.

I like how one YouTube commenter has responded to this video by writing, ‘Their madness fits in neatly with my own’. It’s a play on Wyatt’s lyric to Alfie that serves as a reminder that this is a song about finding ways to be together, of fitting those things which might put us outside the crowd—our eccentricities, in other words—with those of another, of others.

At the end of his liner note for the 1998 reissue of Rock Bottom (also included in Domino’s 2008 reissue), Robert Wyatt provided a typically Wyattian combination of personal and political commentary:

‘On July 26th 1974 (the 21st Anniversary of the attack on Moncada, which was the first action that led to The Cuban Revolution), Rock Bottom was released, and I married Alfie, and we lived happily ever after.’

Happy fiftieth to the unforsqueakable Rock Bottom! And thank you to Robert Wyatt and Alfie Benge and all who’ve sailed with them and in the wake of their compatible lunacies.

Yes, Robin showed Richard a record by Robert called Ruth is Stranger than Richard.

I also wonder whether an early seed was planted here for my future obsession with the human-animal hybrids of Bojack Horseman?

I write about Wyatt’s idea of writing ‘non-misusable’ lyrics in my essay ‘Words Take the Place of Meaning’: Sound, Sense and Politics in the Music of Robert Wyatt’, published in The Singer-Songwriter in Europe: Paradigms, Politics and Place, edited by Isabelle Marc and Stuart Green (London: Routledge, 2016), 51-64. A version of that essay is available on my Late Voice website, along with another essay, ‘You can’t just say “words”: Literature and Nonsense in the Work of Robert Wyatt’ (published in Litpop: Writing and Popular Music, edited by Rachel Carroll and Adam Hansen (Farnham: Ashgate, 2014), 49-62). I’ve drawn on material from both essays for this post.

You loved your nostalgic journey through discovering Robert Wyatt's Rock Bottom. Your reflections on the dreamy, watery soundscape and the intimate lyrics of Sea Song were captivating. The personal anecdotes about Robin’s recommendations added a wonderful touch, too. Thank you for posting this.

Brilliant stuff 👏 Tough to do justice to such an incredible album but you really have