Nightsticks, Water Cannons, Tear Gas, Padlocks: The Musicality of Lists Part 2

In which I turn to list songs and we hear from Blackalicious, R.E.M., Billy Joel, John Grant, Joe Pug, Bob Dylan, Nina Simone, and the list goes on.

In my first post on the musicality of lists, I considered what lists do, how they function and how they sound. I looked at examples from film and literature—especially nonsense literature—and mentioned a few songs. This second part focuses more extensively on ‘list songs’ or ‘catalogue songs’, though I also listen for evidence of listing in songs that would normally fall outside those categories.

List songs

Song, as something other than literature, aims for a more condensed language than most prose, and even much poetry, so it shouldn’t surprise us to see the condensation of experience into listed objects used as a songwriting device. Even so, pure listing remains the exception rather than the rule, which is why people who write about songs have created categories such as ‘list songs’ and ‘catalogue songs’ in the first place.

I’ve already covered a famous example of a list or catalogue song in Songs and Objects, when I used the standard ‘These Foolish Things’ as a way of thinking about how objects get lined up and listed in song texts. There are many more I could have considered—Cole Porter’s ‘You’re the Top’, Rodgers and Hammerstein’s ‘My Favorite Things’, Paul Simon’s ‘50 Ways to Leave Your Lover’, Ian Dury’s ‘Reasons to Be Cheerful, Pt 3’, to start a list—and I’ll be naming others in this post and the one that follows.

There are also accumulative songs that build up and then count down through lists, like ‘The Twelve Days of Christmas’ or ‘Children Go Where I Send You’, a song brought to memorable life by Nina Simone. And, like the examples from Edward Lear and Edward Gorey that I wrote about last time, there are songs that rely on alphabets or spelling-out words, making lists of letters: think of ‘Do Re Mi’ from The Sound of Music or Aretha Franklin’s spelling-out of ‘R.E.S.P.E.C.T.’

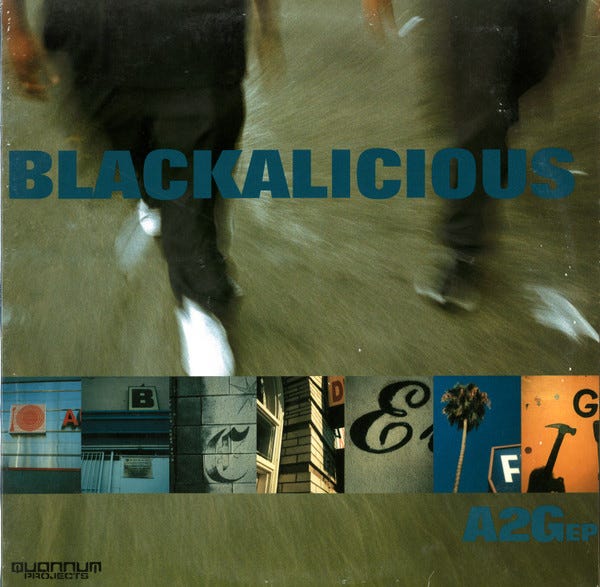

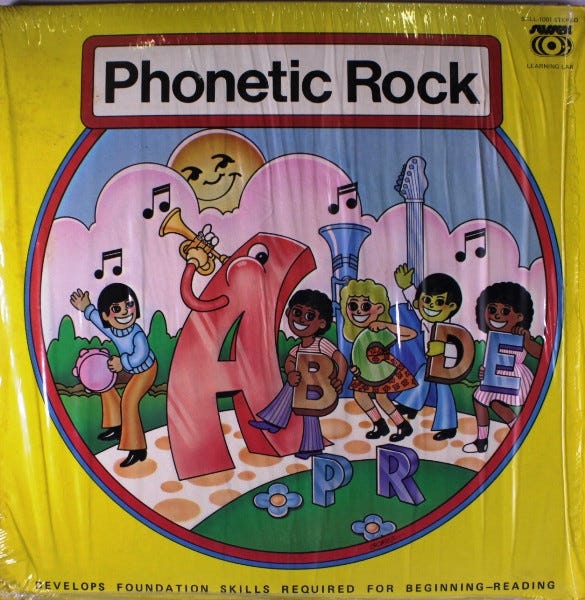

Then there’s the virtuosic listing of hip hop artists. A good example is Blackalicious, whose 1999 EP A2G opens with a track that builds verses on words or samples that feature the first seven letters of the alphabet. ‘A to G’ samples an education record from 1973 called Phonetic Rock that featured songs such as ‘The Vowel A Song’, ‘The B Song’, ‘The C Song’ and ‘The P, Q, R, S, T, V and W Review Song’, creating in the process a weird hybrid of nursery song and rap. Blackalicious’s Gift of Gab takes up the challenge to create words from each letter, extending it to full alphabet in a later track on the EP called ‘Alphabet Aerobics’. In two and a quarter minutes of nonstop delivery, the inexhaustible rapper moves from ‘Artificial amateurs aren't at all amazing / Analytically, I assault, animate things’ to

Yellow-back, yak mouth, young ones' yaws Yesterday's lawn yardsale, I yawn Zig-Zag zombies, zooming to the zenith Zero in, Zen thoughts, overzealous rhyme Zealots!

There are many types of list songs, and many places to locate them. Given the connection between lists, catalogues and encyclopaedic practices, it’s no surprise to find a list of list songs on Wikipedia. The last time I checked, the list contained close to 300 entries. Of course, one of the fascinating and discussion-causing things about lists is what gets left out of them, and several songs that are among my favourite examples of list songs are not included in the Wikipedia list.

Some list songs list multiple items with a brief explanation of why they are being listed: ‘These Foolish Things’ is a good example, as is ‘My Favorite Things’. Some long lists come with a pseudo explanation, which doesn’t really explain the selection of things listed, such as R.E.M.’s ‘It’s The End of the World as We Know It (And I Feel Fine)’.

The song certainly evokes a sense of chaos with its quickfire lists of cultural references that could, at a stretch, be associated with a sense of the apocalyptic. This seems to be how many YouTube commenters respond to the song, mentioning it as an appropriate soundtrack to the ending of the world. But, assuming that it’s either not the end of the world or it’s always the end of the world as we know it, the particular list put together by Michael Stipe arguably doesn’t stack up to anything concrete in the way that earlier catalogue songs do. In terms of building the body of a song from an extended list, though, it does precisely what those earlier songs do.

Billy Joel’s ‘We Didn’t Start the Fire’ is in a similar category to R.E.M.’s: a quickfire list of cultural events that stack up to tell a fragmented story of world events that occurred during the first forty years of Joel’s life. There’s a structuring logic, but not really a sense of what connects these events other than that they took place between 1949 and 1989 and that they display a North American perspective on recent world history. Again, though, the song has in common with songs like ‘It’s the End of the World’, ‘These Foolish Things’ and ‘My Favorite Things’ a foregrounding of list items at the expense of a more conventional storytelling narrative. Verbs may appear in some of these songs but this is mainly when they’re needed to describe the objects in the list, not because they are describing the actions of the song’s author or protagonist.

(Incidentally, since we’re in listing season and I’m writing about lists, it’s worth noting that Fall Out Boy’s cover of ‘We Didn’t Start the Fire’, which rewrites the lyrics to cover events from 1989 to 2003), appears in Variety’s list of ‘The Worst Songs of 2023’.)

Verbs in list songs can also signal a sense of desire, which may be a desire to return to a world of comforting objects, as in John Grant’s ‘Marz’. The verses of this song consist of lists of confectionaries, with the first verse runs as follows:

Bittersweet strawberry marshmallow butterscotch Polar Bear cashew dixieland phosphate chocolate Lime tutti frutti special raspberry, leave it to me Three grace scotch lassie cherry smash lemon freeze

The chorus moves the song into more conventional syntax, with the lines ‘I wanna go to Marz / where green rivers flow / and your sweet sixteen is waiting for you after the show’. The futuristic, science-fiction feel of the first part of the chorus is brought down to earth by the seeming backwards-looking reference to a ‘sweet sixteen’. In fact, it’s all very down to earth. Grant has explained in several interviews and concert performances that the song was inspired by a confectionary shop called Marz that he frequented as a child, and which sold drinks called ‘green rivers’. There is a melancholic, bittersweet nostalgia to the track’s music and Grant’s vocal delivery, which, in combination with a knowledge of the song’s backstory, works to evoke a nostalgic desire that is at once specific to its author’s experience but translatable to a much wider audience who have had similar experiences.

To my mind, Grant’s song works like Joe Brainard’s book I Remember, which is an extended list that combines deeply personal recollections with collective memories, showing how our ability to move between personal and public spheres is one of the ways in which we translate experience and connect with one another. The listing of experience and the cataloguing of memories is a crucial part of how we understand ourselves as humans.

Looking at online responses to ‘Marz’, I’m struck by how many mention the beauty of the melody and the vocal delivery, picking up—whether consciously or not—on a long-established trope connected to evocative voices, namely that certain singers could sing a shopping list or a phone directory and still move people to tears. For many listeners, Grant seems to have avoided a danger that is perhaps more likely to emerge in list songs than in more conventional narratives: the danger of droning on, becoming boring or sounding monotonous.

I’m reminded again of Eric Maschwitz hearing the setting of his lyrics to ‘These Foolish Things’ by Jack Strachey and feeling ‘bitterly disappointed’ by the melody. Billy Joel, meanwhile, would come to reflect negatively on his own melody for ‘We Didn’t Start the Fire’, describing it as ‘like a dentist drill’. As well as thinking about the musicality of lists, then, we also have to consider the potential for monotony. There seems to be simultaneously something in lists that leans (or lists) toward sonification but also something that hampers melody.

This threat of monotony is also connected to the potential for endlessness and exhaustion in lists: what the English language version of Umberto Eco’s La Vertigine della Lista calls ‘the infinity of lists’. Lists can summon up the infinite because even a short list can suggest a much longer one. As Francis Spufford notes, a short list like Lewis Carroll’s ‘shoes and ships and sealing-wax … cabbages and kings’ is ‘a thumbnail sketch of everything, his five listed elements representing the idea of profusion’.

I think the same can be said of an only slightly longer list tucked into Bob Dylan’s 1984 song ‘Jokerman’. Dylan sings of ‘Nightsticks and water cannons, tear gas, padlocks / Molotov cocktails and rocks behind every curtain / False-hearted judges dying in the webs that they spin’. These items have more in common with each other than Carroll’s handful in that they are all connected to law enforcement; even so, the strangeness of these words appearing mid-song offers the opportunity that a more extensive list could follow, or that almost anything could be added.

Elsewhere in Songs and Objects I hope to touch upon songs where even a brief list of objects—such as those given in George Jones’ ‘A Good Year for the Roses’ or Gram Parsons’ ‘Brass Buttons’—hint at much larger conglomerations of object effects, of new lives built upon the things that remain when old lives fall apart. For now, however, I want to consider some different categories of list song as I hear them, though I’m not going to list them.

Categories

In starting to categorise list songs, I’d suggest that there are songs in which micro lists such as those just mentioned hint at a larger object world, where a few parts are taken as representative of something more extensive that doesn’t need exhaustive cataloguing. I’d contrast these with songs where the list remains the structuring logic throughout. In this second category, I’d then distinguish between songs that provide some kind of ‘explanation’ of the list—also noting whether that explanation comes before or after the list—and those that don’t. An example of a list song that seems to offer no explanation is Joe Pug’s ‘Great Hosannas’. The first verse the song runs like this:

Aspirations Flat refusals Childhood bedroom's Disapproval. Would-be authors Erstwhile singers Costume jewelry Ballpark figures Naked power Base excitement True love's call gone Unrequited.

There is no chorus in the song, nor any repeated lines to offer an explanation of the imagery. The list still invites interpretation, however, as in the following description by Stephen Deusner in American Songwriter magazine:

‘Drawing out his syllables like dying breaths and blowing on a harmonica like it’s a church organ, [Pug] runs through a list of buzzwords and catchphrases, from the corporate (“paid compassion, sponsored mercy”) to the banal (“payday lenders, closet smokers”) to something akin to suburban surrealism (“floodlights trained on open faucets”). The verses are animated by an almost palpable sense of dread, yet in finding the courage to face an uncertain future, Pug finds some hope that he can make it better.’

As with R.E.M. we find here a random-but-evocative list being connected to a sense of doom or dread. At the same time—and this is hinted at in Deusner’s mention of hope—there’s a kind of musical triumph in bringing the list to life. What might feed foreboding in the written or even spoken list can become something else when its sonic contours are traced in a memorable melody and its objects rhymed through assonant letter sounds and vocal inflection.

Many songs exist somewhere between the extensive sentences of prose and the formal starkness of the list. Songs take on aspects of both concentrated prose and expanded lists. Songs look more like lists than prose does because of being set in lines like poems. They sound like lists because of their repetitive nature: repeating both meter and melody and cadence.

But for songs that have quite developed (and hence near-prose-like) phrases, we are looking at and listening to a different kind of list to those songs that line up objects, events or names. Take Bob Dylan’s ‘Angelina’, for example. An outtake from the 1981 album Shot of Love, it appeared ten years later on the first volume of Dylan’s Bootleg Series in 1991 and, in different form, a further two decades later on Springtime in New York: The Bootleg Series, Vol. 16.

This is a song that wears its artifice loudly, coming across at times like an attempt to find words that rhyme with ‘Angelina’. At moments that have metrical privilege and which Dylan exaggerates with vocal emphasis, each verse leads to an initial peak with a word from a similar rhyming family: ‘concertina’ in verse 1, ‘hyena’ in verse 2, then, in subsequent verses, ‘subpoena’, ‘Argentina’, and finally ‘arena’. Each verse ends with a second peak, which is always ‘Angelina’. (On BobDylan.com and other lyric sites, the verses are counted differently, with each ‘Angelina’ section counted as a separate verse; this also happens with ‘No Time to Think’ discussed below. However, in each case, I count as a verse what leads up to the refrain and what is also delivered as a musical unit.)

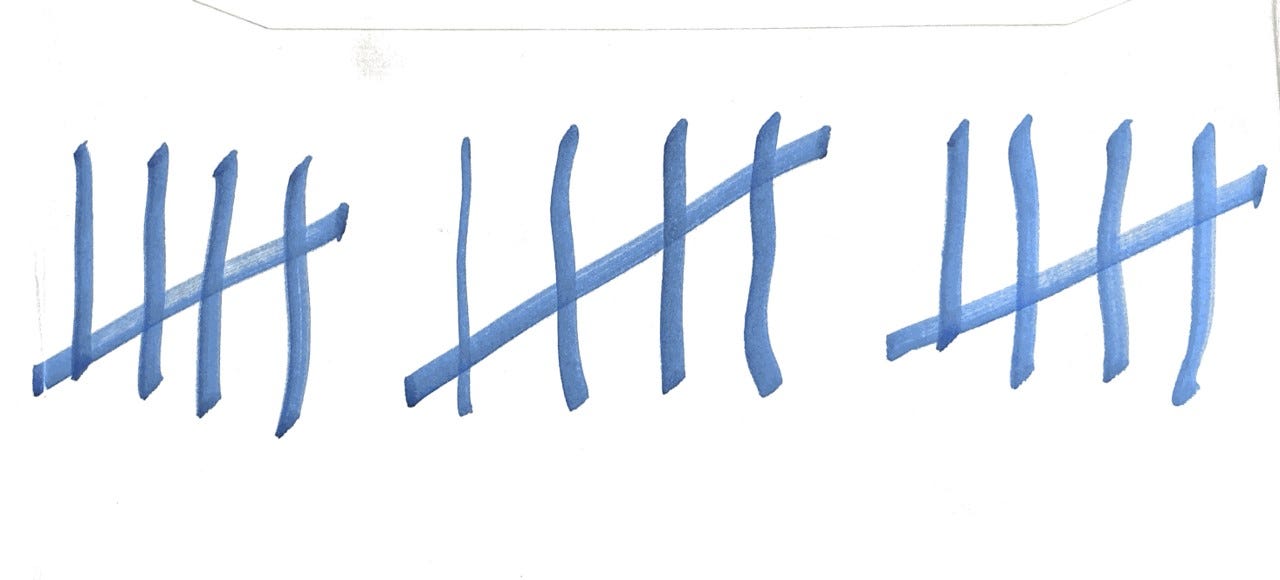

The effect is to render the in-between lines—the lines that are working in Dylan’s song to deliver these privileged ‘Angelina’ rhymes—as somehow less important, to relegate them, we might conclude, to a list-like bulking-out. But rhyming agents can also be thought of as list elements, objects lined up on the shelf of the song (or at the song’s right-hand column, if we wanted to be more literal in terms of how song lyrics look when written down). So here we have different listing elements within the song: the in-between lines that bulk out the narrative but do have a certain listing quality (also making it list or lean a certain way) and the summative ‘Angelina’ rhyme objects that appear in serial regularity. It’s a bit like tally marks used for counting that proceed in fives, with four vertical lines crossed through by a diagonal fifth.

A similar strategy can be found in Richard Thompson’s ‘Valerie’ which places strategically emphasised rhyming words in each verse: ‘gallery’, ‘calorie’, ‘salary’:

The technique of setting different lists against each other can be found in many Dylan songs. One example is ‘No Time to Think’, from the 1978 album Street Legal. Many lyric repositories, including BobDylan.com, list this as a song of eighteen four-line verses, but I tend to think of it as a song structured around nine blocks of eight lines, each block culminating in the song’s refrain of ‘no time to think’. Each block follows the same structure, with an in initial four lines of closely rhymed words that have a listing quality partly because of the objects they present and partly through the piling up of rhymes within a condensed space. These are followed by four more lines that always begin with a four-word list. Here’s the seventh block:

Warlords of sorrow and queens of tomorrow Will offer their heads for a prayer You can’t find no salvation, you have no expectations Anytime, anyplace, anywhere Mercury, gravity, nobility, humility You know you can’t keep her and the water gets deeper That is leading you onto the brink But there’s no time to think

I’ve chosen this block because the listing here is really foregrounded. Leading with the ‘of sorrow/tomorrow’ rhyme that picks up sonorous connections in ‘war’ and ‘lord’, we also have the repeated ‘no’, the ‘salvation/expectation’ duo and the rolling-off-the-tongue series of ‘anytime, anyplace, anywhere’, all of that before we even get to the core list in this block: ‘mercury/gravity/nobility/humility’. The effect of nine iterations of this structure is to create a feeling of a lyrical superabundance that hints at infinity, at a self-generating model of song production.

I’m thinking here also of Leonard Cohen’s ‘Hallelujah’, a song similarly packed with religious imagery and which again has a verse structure that could yield to infinite possibilities, as well as the ongoing challenge of coming up with rhymes for ‘hallelujah’. Cohen often spoke of the song as not having a definitive version, with multiple versions using different combinations of verses and lines. Only after a multitude of other performers started releasing their own versions and after Cohen brought the song back into his concert repertoire for his late triumphant series of concerts did the song start to gain a kind of stability in terms of which verses were included.

Dylan’s ‘No Time to Think’ has hardly become a contemporary standard in the way that ‘Hallelujah’ has, but it shares the sense of superabundance and infinite potential in its structure, rhymes and lists.

Another example of a song in which one list responds to another is ‘Ain’t Got No (I Got Life’),' Nina Simone’s rendition of two songs from the 1960s musical Hair. Over the years, I’ve tended to hear Simone’s mashup of these songs as being about ownership and possession in two senses: firstly, the assertion of bodily presence and identity in the lyrics and, secondly, Simone’s performance of other people’s material.

The first type of ownership is laid out explicitly in the lyrics of the song through the ‘ain’t got no’ section (detailing absences) and the ‘I got’ section (confidently and hopefully asserting presence). That Simone conflates what were two songs in the original musical into essentially one song is evidence of the second type of ownership: she makes this combination hers. In doing so, she connects the ‘got no / I got’ lyrics to a long tradition of black American vernacular song, a lineage that can be traced back to the classic blues queens of the 1920s (especially Bessie Smith, one of Simone’s great influences) and forward to the body-conscious identity-affirming music of contemporary artists such as Solange Knowles.

The ‘ain’t got no’ section consists of a long list of attributes: no home, no shoes, no money, no class, no skirts, no sweater, no perfume, no bed, no man, no mother, no culture, no friends, no schoolin', no love, no name, no ticket, no token, no god. A brief bridge follows in which Simone asks ‘what have I got / [that] nobody can take away?’ The answer comes with another list, the ‘I got’ section: my hair, my head, my brains, my ears, my eyes, my nose, my mouth, my smile, my tongue, my chin, my neck, my boobies, my heart, my soul, my back, my sex, my arms, my hands, my fingers, my legs, my feet, my toes, my liver, my blood, life and freedom.

‘Ain’t Got No (I Got Life)’ is one of the songs analysed by Emily Lordi in her book The Meaning of Soul. She notes the way the two lists work with and against each other to play on the interplay of absence and presence. Of the first ‘got no’ section, Lordi writes:

‘The repetitive, nonteleological lyrical and musical structure would grow tedious in the hands of a less compelling singer. And Simone is relentless, resisting the embellishments that would ease the monotonous pressure as if determined to carry the song off through sheer force of vocal charisma. But her approach does serve a purpose: to elicit relief when the song finally shifts.’

And of the second ‘got life’ section, she writes:

‘Simone transforms expressive deprivation into sensual survivorship by performing an extravagant, virtuosic seizure of multiple expressive modes. She also lays claim to the pleasures and pains of the black female body — a body that “Life” lyrically fragments in order to lovingly reclaim and reassemble, piece by piece … Rather than reflect a fragmentary subject, then, Simone’s intergeneric work seeks to consolidate her self and her community.’

Lordi is keen to connect the triumph of Simone’s performance to the context of black experience in the 1960s and the resilience of soul music more generally. I agree with this reading and have noted in my own writing on Nina Simone that it is quite different to witness this artist performing this song in the times and places she did than it is to hear and see it in the original context of a hippie musical. It connects black womanist affirmation to the politics of the body in ways that compare to other Simone songs such as her composition ‘Four Women’ (itself a kind of list song).

From the perspective of listing songs, Simone’s ‘Ain’t Got No/I Got Life’ takes its place among the others I have mentioned here, demonstrating how musical abundance can emerge from potential monotony and how music can rescue lists from their own worst tendencies. The virtuosic musician works with against the relentless virtuosity of the list.

I plan to post the third (and, for now, final) extended foray into the musicality of lists prior to the end of the year. I’ll turn to examples by Tom Lehrer and Bob Dylan (again) and return to the kind of relentless virtuosity shown by Gift of Gab and some of the other performers mentioned above. Having done that, I plan to resort to some listing of my own as a way to mark the turning of the year.

The text above is a slightly revised extract from the fourth episode of the Songs and Objects podcast, originally released in November 2021. I’ve divided the episode into three for this version. Part 1 is here and Part 3 will follow soon.