‘I started running, and the concrete turned to sand’ — Bill Callahan, ‘Jim Cain’

Kilometre 1

It’s 7am on a Thursday in July. My wife and I leave the house and walk the short distance to the point just over the main road where we start our runs. We jog along the path between the HMRC building and the school, turning left onto the wagonway before the hospital. Sometimes at this hour it’s too crowded to run here, as people make their way to work from the Metro station, but we’re between trains this time round. Later it will be packed with school children, but we’re too early for them. There are still people around, the usual morning bustle to be found in the suburbs of a busy city: dog walkers, cyclists in helmets and hi vis tops, the schoolkids with a longer walk who have to leave earlier, workers, other runners.

The ground is hard here as we gradually pick up speed down the wagonway towards Benton Road. Along the perimeter of the HMRC building the hedges abound with hawthorn, blackthorn, dog rose, elder, blackberry, hazel and field maple. Yarrow, nettles, thistles and dock reach out at us. There are splashes of yellow from clumps of ragwort. At this time of the year, many of the tree branches hang low over the path and it becomes a challenge to pass other wagonway users without getting a faceful of leaves.

I’m not thinking about music at this point, though I’m aware of setting a rhythm as the two of us move along the path, slowing slightly so that we can stay together and because I want to make this a long run. I’m aiming to beat Monday’s 18.5K, the longest I’ve done since taking up running again eight months ago. We settle into our pace.

Kilometre 3

Benton Road is not too busy yet and we’re able to cross quickly. This won’t be the case in an hour or so, when all pedestrians will have to stop for the all-important road traffic. The wagonway continues on the other side, with wilder hedges to our left—fewer trees, more bushes full of what would be classed as weeds if they showed up in the gardens around here. To the right is a long wall that borders the sports grounds, grand old trees harboured behind, shiny leaves of rhododendron peeking over. We cross another soon-to-be-busy road and into a wilder patch of the wagonway, the hedgerows hanging over on both sides. This is the part of the route that feels most like a green corridor or tunnel, an enclosure of verdant summer growth. I take a faceful of leaves, thankfully with no hard branches or thorns. The softest of slaps, but a reminder to stay alert.

At the 2.25K mark we reach a quieter residential street. This is the point where my wife will turn back, heading home to do some work before we have breakfast. I cross the street and continue on the wagonways and footpaths, tracing the route I started using a few months ago when I set the Rising Sun Park as a destination for runs and semi-runs. At that time, I’d invariably need to slow down to a walk for some sections as I had yet to discover a tolerance or pace that would keep me running for longer.

It was my wife who got me running again, after a gap of twenty years. I was a good runner in my teens, competing for my school and winning a trophy for my age group in the Bovey Tracey half marathon, a hilly thirteen-miler that snaked through the lanes on the edge of Dartmoor. I didn’t keep it up past my twenties, though, and an attempt to restart in my early thirties proved short lived. Prior to last November, I hadn’t tried running since 2003. My wife started doing one of the weekly ParkRuns in our area last year with a friend. I was resistant to join them at first but, after trying it out one day when my wife would have been otherwise going alone, I got the bug and have been doing it ever since. I can’t quite recall how we got from the endorphin rush of a few 5K park runs to me agreeing to my wife’s suggestion that I sign up for the Great North Run, but sign up I did at the start of this year. In early September I’m due to run the world’s biggest half marathon, which conveniently starts in the city where I live.

That’s why I’ve been building up the distance, working on pace, rediscovering and nurturing my penchant for the long form.

Kilometre 5

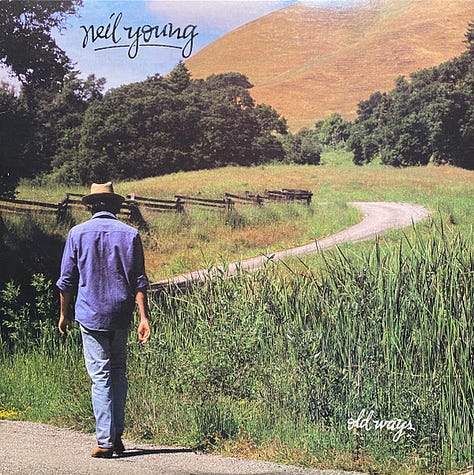

‘Headed out to where the pavement turns to sand’ — Neil Young, ‘Thrasher’

The tarmac and gravel of the wagonways give way to softer terrain as I enter the path between the railway and the football fields. We’ve had a wetter-than-usual July and much of this path is puddled. The smaller puddles can be managed in strides; the larger ones I can generally skirt around while still avoiding the branches that arch over the pathway. The softer ground makes for a pleasant change and also makes me feel more like I’m in the countryside. I almost am: where does the countryside start exactly?

There’s a point on this stretch, just where I turn right along the north border of the Newcastle United training ground, where I’d often want to stop running and either loop back homewards or walk for a bit before picking up the pace again. Now I keep going, slowing only to get across the biggest puddles on the route. Past the railway bridge I’m on firmer ground, running into the sun with the landscape looming as silhouette in front of me, inviting me into its mystery.

I began this Substack last November, in the same week I started running again. Soon after that, I started attending a daily online writing group, trying to find a way into regular writing that my increasingly busy day job had kept me from in recent years. These activities became intertwined for me, and I’ve had many thoughts about writing while on my runs. Even if they haven’t always been easy to keep hold of, the things I think about when running allow a way of working through ideas that continues when I am back at my writing table. Mainly, though, it is the idea of accountability—of showing up and keeping at it—that has been the strongest connection I’ve found between regular writing and regular running. That and the idea that comes through ParkRun, the online writing group and the corners of Substack that I tend to be drawn to that it’s not about being the fastest or having the most words, likes or followers that matters. The metrics will keep coming, but I can jog on by, or write past, those particular ways of measuring success or failure, building confidence instead in taking ownership of something and knowing why I’m doing it.

Kilometre 6

The path up the west border of Rising Sun Park is steeper and rockier than the stretches I’ve covered to get to this point. It’s damp but not puddled, as the recent rainwater has a chance to run off it. To my left as I run uphill, there’s a fast-flowing stream, heard but not seen as I look down to avoid tripping on this rougher ground. The sound and the terrain put me in mind of moorland or mountain streams. This is the closest I get to what I imagine fell running must be like.

It was while running down this slope the other day that I got to thinking about how the landscape felt as I passed through it. At first, this was prompted by the feeling of the ground beneath my feet; later, it became about other ways of sensing my surroundings. There’s the changing terrain, of course—this route unfolds over tarmac, gravel, concrete, mud, puddles, rocks and occasional tree roots, via pavements, wagonways, bridleways, roads, trails, bridges and banks—and there’s also the feel of tensed-up feet, relaxed feet, the rocking motion from the back of the foot to the front, hitting the ground and lifting off, the way the running shoe relieves the pressure here or adds some resistance there. And there’s what’s happening around and to my body: the warmth of the rising sun, the cooling breeze and sense of recent rain, the opening and closing of the horizon as I move between hedgerows, woodland and open ground, the musty smell of damp leaves, the tang of pollen, the shifting focus on blue, grey, green and brown, the sounds of birds, cars, sirens, cyclists, dogs, trains, other runners, the puff of my breath, the crunch or thud or plop of my feet meeting the different ground textures, the swish of waving greenery.

And music, after all. Not only the steady rhythm of my feet on the ground, the breath through my nose and mouth, or the sense of a measured pace. Songs are there too, though not delivered in any obvious way via an external device (save for the occasional car stereo through an open window or pumping as resonance from the body of the vehicle), because I’ve yet to take to wearing any kind or earbuds or headphones or using an object to deliver a soundtrack. No, this is music that’s already inside my head, music coming from an inner jukebox, sometimes as if from nowhere, sometimes prompted by a thought or a feeling or overhearing a word or phrase.

When choosing a title for this text—‘How the Landscape Feels (with Music)’—I decided to bracket ‘with music’ because my starting point, unusually for this newsletter, was not a musical topic. I didn’t have a song in mind, or an artist or genre or anything resembling a ‘songs and objects’ theme. At the same time, I suspected music would find a way in, as it always does with me, and I knew that I was never really without music when I went running.

There are several ways I’ve thought about how the landscape feels with music. Even if I don’t tend to listen to music via external devices when running, I’m no stranger to using them when on walks, soundtracking my journeys with albums. playlists and podcasts. And there’s no denying that the immediate environment does feel different in such situations. (My former colleague Michael Bull has written extensively about this). There are also the countless road trips and shorter journeys I’ve taken with music playing, whether as a passenger or a driver, whether using public transport or private. I’ve thought a lot about those experiences over the years and enjoyed reading academic studies on the topic.

I’ve also thought about imaginary landscapes when exercising indoors or, indeed, when imagining exercise. And I’ve been drawn to evoke metaphors of landscapes and journeys over and over when writing about music.

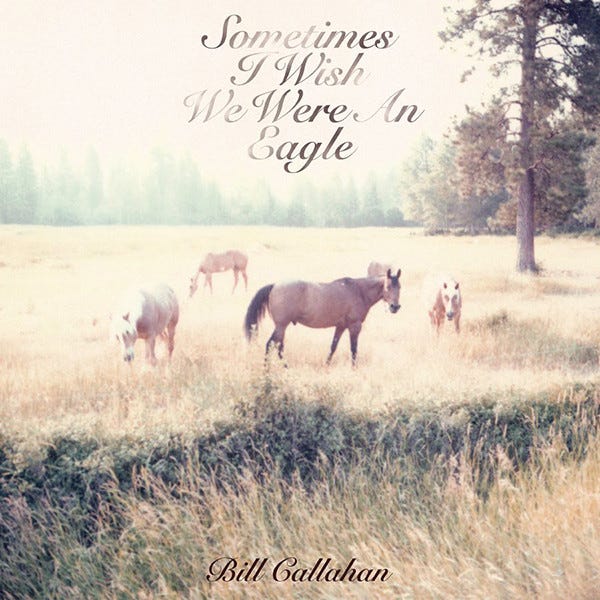

Songs that evoke landscape seem to me a different category because they might also include lyrical content that describes the environment. I think here of songs by Bill Callahan, Richard Dawson and some of the other songwriters whose work I’m studding this text with. There are many others I could choose, but these are some of the musicians who I’ve been writing about and/or listening to recently, or whose songs came into my head when prompted by certain phrases or flashes of thought.

Dawson’s 2022 album The Ruby Cord remains, for me, a masterpiece in evoking how the landscape feels as you move through it. It’s there in several places on the album but most obviously on the epic opening track ‘The Hermit’, where Dawson sings of flora (rowan, bluebells, moss, bilberries, gorse, heather, wild garlic), fauna (chiffchaffs, caterpillars, fallow deer, crayfish, kittiwakes, miner bees) and funga (death caps, slippery Jacks, amethyst deceivers, fairy rings, penny buns, hen-of-the-woods). I made a start on recording my thoughts on this incredible work in a Substack post last year, but there is so much still to uncover about how this song and album convey the wonder of moving through real and imagined worlds.

Kilometre 8

‘Vaporous shafts of a burgeoning sun / Skewer the forest floor’ — Richard Dawson, ‘The Hermit’

Another green corridor, though here one green wall drops away to the right at the halfway point to reveal tall reeds growing from the leat between the trail and the fields. At the start of this stretch, where the path hairpins behind the car dealership to keep its users just away from the busy main road (a reminder that this park, for all the early morning tranquillity it harbours, is bounded by some of the outer city’s main commuter routes), there’s a patch of dappled light coming through the trees to the left. Seeing the patterns of light on the ground—what Dawson describes in ‘The Hermit’ as ‘a basketweave of glowing mud’—I’m reminded of how my mother would always point to such patches when we were out on woodland walks. A painter, she was drawn to the ways light moves through the landscape, what it does to the world and its objects.

Thinking again about what music I’d play if I did bring headphones on my run, I think I would go for something relatively upbeat, but probably not too fast: mid-tempo metal or electronica, for example, rather than thrash or techno. Perhaps the galloping rhythm of some Iron Maiden (a group I rarely listen to at home these days, though they were a major part of the soundtrack of my youth and hence a way to connect back to that jogging teenager), or the way Richard Dawson appropriates that sound in songs like ‘Jogging’ (appropriately!), or maybe the varying tempos and textures of classic Grandaddy/Jason Lytle, which would alleviate my itch for guitars, keyboards, glitching tech and lyrics that veered between desperation (‘Hewlett’s Daughter’?), elation (‘Now It’s On’?) and a kind of ironic motivation (‘Get Up and Go’?).

I might look to something that was obviously based on loops, like ‘Get Up and Go’, because I’m drawn to the connections between shorter and longer loops: the networks of the body’s organs and limbs engaged in repetitive exercise; the loops of the running routes I follow; the looping song fragments that accompany me regardless of whether I’m carrying a playback device.

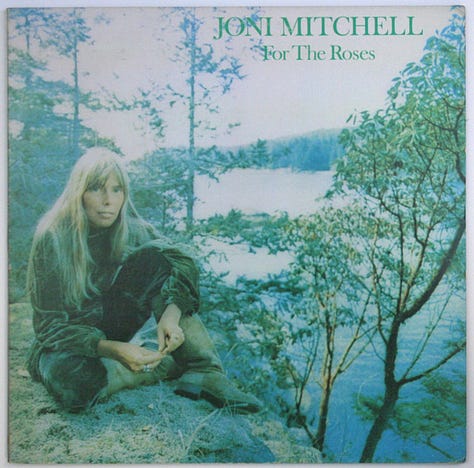

And, given that I do tend to engage in the kind of repetitive but evolving thought processes that suggest both circles and spirals, these reflections sometimes move me to think of life as a circle game, or as a journey, road or river. I’ve tried before to connect those thoughts to music and how art accompanies and sheds its own dappled light on life’s journey and our attempts to come to terms with it. In the conclusion of my book The Late Voice, with Joni Mitchell, Bob Dylan, Jim Harrison, Hart Crane and others at the forefront of my thoughts, I wrote about the ways that roads, rivers and seas are deployed in connection with the journeys and the landscapes of human lives.

Kilometre 10

‘You can always come back / but you can’t come back all the way’ — Bob Dylan, ‘Mississippi’.

Horses grazing in a field at Rising Sun Park suddenly put me in mind of an album cover as I catch them first from the periphery of my vision and then turn to gaze at them. It’s the cover to Bill Callahan’s Sometimes I Wish We Were an Eagle.

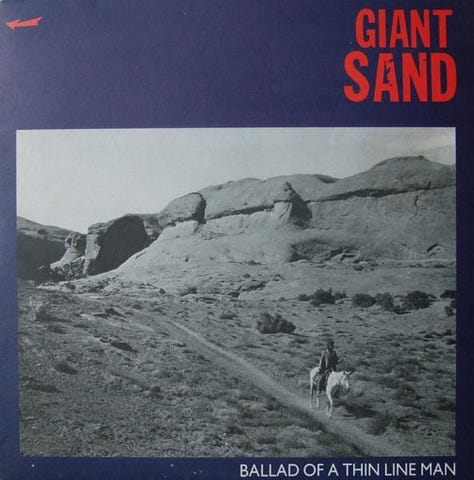

Album covers are, of course, another way that landscape gets attached to music. Running down the lanes of the Rising Sun Park, I’m reminded of several, including Neil Young’s Old Ways and others by Callahan, Will Oldham, Joni Mitchell, Giant Sand and Grandaddy. Some of them, like Young’s, translate to landscapes I pass through quite regularly. Some, like Grandaddy’s, remind me of the ways humans treat nature and commodities (I curse each time I jog past an area of the Rising Sun Park that is victim to fly tipping). Some are ones I only know through the mediation of album covers, films, videos, magazines, books and paintings. I recall how those Giant Sand covers helped me understand something of the musical world that Howe Gelb was projecting, though the closest I’ve yet to come to them has been in South America rather and further north. This was something I wrote about in The Late Voice when trying to describe ‘sounded experience’:

‘I recall, for example, that the first time I encountered a real desert, I felt as if I were familiar with the landscape partly from having seen similar terrain in films (especially Westerns, as I recall) and having read about it in books, but also from having heard so many songs (especially US country and folk music) that seemed to narrate the experience of such a space (though I did not encounter my desert in the USA). I might say that a voicing of the desert had taken place before I ever arrived in it, one that did not in any way diminish the wonder of being there ‘in the flesh’, but of which I was aware as something feeding into my experience, feeding an intuition of déjà-vu.’

Kilometre 12

‘Hundreds of miles going nowhere’ —Richard Dawson, ‘Jogging’

‘But the miles, they never seem to end / As if you're in a dream, not getting anywhere’ — Iron Maiden, ‘The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner’

Tiredness kicks in. I untense my toes and let the technologies of road and running shoe carry the lagging machinery of my body for a while. I’m on a slight downward gradient, making it easier to give over to this process. It’s sometimes possible to do the same thing on a slight upward slope too once momentum has established itself.

My breath is more noticeable now and I’m aware of the world moving through my body as my body moves through the world.

In thrall to momentum and enjoying the caress of wet grass on my legs, I try to avoid the nettles harbouring at ankle and shin height. Now that it feels harder to move sideways, now that going straight forward seems to be the only option, I resign myself to the likelihood of an occasional sting.

I’m thinking about other ways of passing through landscapes. I think, as I often do, of the tree I always notice shortly after crossing the Cornwall-Devon border on the A30. It stands aloof in the middle of a field far to the right of a group of other trees. It’s on a hill and, from the road, sits at the perfect point on the horizon to emulate the kind of ‘tree on a hill silhouette’ that you might see on a greeting card. No matter how many times I’ve driven past, I still get tricked into thinking that the tree is to the left of the road. As the car moves through the road’s gentle bend, I’m reminded that it’s over on the other side. I think about that tree as an object I attach to the experience of driving and listening to music. I like to think that I’m always seeing it while listening to Neil Young’s ‘Like a Hurricane’, but in reality this only happened once. Why can’t I remember the songs that were playing every other time I approached that bend and saw the tree drift across the windscreen from left to right?

Kilometre 14

‘it takes me out there for just a little while / And the years fall away with every mile’ — Steve Earle, ‘The Other Kind’

The sun is behind me now and my shadow stretches out in front, beckoning me on. As I run the lane between the A186 and the row of houses near the railway bridge, a car approaches. The same thing had happened on the outward stretch and I’d ducked into a gap in the hedge to let the driver pass. This time I decide to keep going as it looks like there will be enough space between the car and the hedge. Even so, I instinctively veer into the hedge as the car and I pass each other and I feel the hot stab of nettles on my thigh. The pain is intense and I cry out. I feel I may have to stop but manage to keep running. It feels like I’m moving at a crawl now, but the tracker on my wrist tells me I’m still on the pace I’ve been for most of the run. I marvel again at the body’s momentum. My mind is taken off the pain by the sight of a bird perched on a metal farm gate, silent and unafraid. Soon after, a magpie screeches as I pass, and I choose to hear it as encouragement to keep going.

Songs are like tattoos. Joni told us that. She was right, of course; songs get into your skin, they mark you, they travel with you through life. They ‘crown and anchor’ you. They’re part of the landscape of your body as well as how your body gets to inhabit the world. When I think about how the landscape feels (with music), I also think that songs are like ragwort and thistles, nettles, brambles and dock. They attract, they sting, they catch, they invade, they spread, they hurt and heal. They help you to keep going.

Kilometre 15

‘Wet life of mud!’ A line from a poem I wrote in my mid-twenties comes back to me as I make my way back through the wettest part of today’s route. I recall how I used to write things like that while staring through coach windows, trying to capture how the landscape felt as I moved between towns and cities and villages. I remember that line coming to me on a rural route while I sat behind the screen of glass and watched the unforgiving winter fields roll by.

There’s an old briefcase in the attic of my house, its brown leather worn, its brass fastener dulled, its liner frayed. Inside are various handwritten and typed poems, songs and fragments of prose, the last remnants of my youthful plans to be a writer. They are mostly poor, with occasional flashes of insight or invention. I keep them for some kind of connection with that period of my life, along with the small press magazines I’d sometimes submit to and which would very occasionally publish something I’d written.

It turned out that I was better at writing about other people’s poems and songs than writing my own, so that’s what I turned to doing once I’d put those things aside.

There was nothing wrong with wanting to try and write about how the landscape felt when I was younger. Some of the tools I had then were better than ones I have at my disposal now. I had, at least, the confidence in insight that comes with youth, and that’s no small thing. I had a wonder about the world, too, one that might have floundered in articulation, dragged down by so many poetic styles of the past that I was drawn to without knowing which to choose or abandon. Perhaps that was it: a confidence of insight not matched by a confidence of articulation.

No matter. I have more of the tools now, more of a sense of what I want to say and what I don’t want to say. I have a voice, though I’m still drawn to trying other voices on. I try not to be concerned about originality too much these days, though I still try to do my own thing. I’m poor at taking advice, and giving it for that matter. When an idea gets into my head, I like to run with it. That’s especially the case when, like this one, it’s an idea that got there via my feet.

In claiming not to be original, I mean that I always check for previous evidence of the ideas that come to me as if anew. I often find notes I’ve made for similar things years before. I also have to check on what others have done; the years I’ve spent working in academia have at least implanted that responsibility in my head. While working on this piece, I found an interesting article by Andrew Barnfield on the sensual experience of the landscape (particularly the built environment) in recreational running practices. I came across it by googling the term ‘how the landscape feels’. The article also reminded me of the work of Tim Ingold. I haven’t drawn on these sources in this piece, but they offer further journeys to take.

Kilometre 16

‘From the village, still at-dream we fly / Cow silhouettes and starlit molehills sailing by’

‘Along weedburst motorways we tear / Past the tangled silence of our emptied cities’

‘Over unseen churning seas we go / Neverending passage through the cold and dark’

— Richard Dawson, ‘Horse and Rider’

A bramble presses itself into my upper arm. A quick sharp pain, less invasive than the nettle sting but enough to remind me that the landscape is to my side, not on my side. It’s not on anybody’s side. We can’t ever know the landscape’s perspective or how it feels.

Richard Dawson’s ‘Horse and Rider’ is going through my head, though really I’m a mess of song fragments by this point. It hasn’t been dark for a few hours—you have to get up absurdly early to steal an hour on the sun in the northeast English summertime—but Richard Dawson’s and Neil Young’s narratives of pre-dawn journeys have become in-head staples. The disconnection between what a song lyric is literally about and what it evokes or connects to is becoming a recurring theme. A song about riding or driving through that kind of landscape at that time of day becomes a song that makes sense while running through this kind of landscape at this time of day. A song sent out from the perspective of that point in the life course suddenly makes complete sense while navigating this one.

Kilometre 20

‘Cartwheels turn to car wheels through the town’ — Joni Mitchell, ‘The Circle Game’

The relativity of the homeward stretch. Eight months ago, I could barely envisage completing a 5K run. Now it feels like the last 5K of this one is just the homeward stretch. But, as tiredness mounts, I’m very aware of shorter homeward stretches within that longer one. The last 2K, then the perimeter of the HMRC car park, the short span of the road my house is on: all of these are homeward stretches, and all times and distances are relative.

I recently enjoyed a piece of music writing that got brilliantly to the connection with landscape. It’s from Stephen Troussé’s text about Joni Mitchell for the July 2024 issue of Uncut:

‘After the rough and tumble of Rolling Thunder, in contrast to the Babylonian big band splendour of Court And Spark, Hejira has an eerie desert beauty, a dawning Georgia O’Keeffe radiance. Mitchell, Carlton and Pastorius are an uncanny, unearthly soft power trio. They never played together, never even met in the studio – the guitarist recorded in the daytime, while Pastorius overdubbed deep into the night, leaving Mitchell to tune and weave their strange frequencies together. Like many a mystic, Mitchell finds illumination in desert visions. On the title track she and Pastorius ride out together, starsailing the solar winds into a cosmic wilderness beyond attachment, where we’re “only particles of change orbiting around the sun”. She finds a fellow traveller out in the bleak terrain of the burning desert, with Carlton’s guitar shimmering amid the vapour trails, in the ghost of Amelia Earhart, patron saint of solo voyagers.’

I often think of landscape when I listen to Joni Mitchell (especially Hejira), but I haven’t found a way of talking about it yet, not as well as Troussé. I like the way the loneliness of the journey comes out here, whether in the journeys across America that Mitchell took during the writing of the album or the loneliness of the studio work that brought the songs to the form we came to know them by.

As I run the homeward stretch of this run, I encounter more people than before. It’s closer in time now to when work and school start, and closer physically to where such things are happening. If the approach to the Rising Sun Park and the park itself are where the city meets the countryside, this last stretch is very much part of the working city. It feels crowded after the relative isolation of the rural kilometres and I find myself thinking back to when I first heard of ‘the loneliness of the long-distance runner’. As a teenage runner, I was aware enough of the Alan Sillitoe story and the Tony Richardson film to identify with the phrase before I encountered it as a song title on Iron Maiden’s 1986 album Somewhere in Time. As someone who did much better at running than social skills, the phrase rang true for me. And even when I started doing a bit better at the social side of things, there was still a part of me who liked to be alone for periods and for whom the rediscovery of long-distance runs would prove something to embrace.

I find myself wondering whether the crowds who will be there to cheer the participants of the Great North Run on, and who everyone assures me are a huge part of what makes it possible—even enjoyable—to complete the event, might in fact be a cause of anxiety for me. I don’t think so, but the run I’ve just completed has felt like a victory for self-motivation and a way of being ‘alone’ in the world. And it’s led me to think again about the way the landscape feels—to me, while running, with and without music—and, for that, I’m grateful.

I'm taking part in the Great North Run, the world's biggest half marathon, for the first time in September 2024.

I'm running in support of Mind, the mental health charity. Mind is there to make sure no one has to face a mental health problem alone. Please help to show everyone with a mental health problem that they are not alone by supporting my run for Mind.

The money we raise will make a real difference for people living with a mental health problem. Thanks for your support!

I absolutely loved this piece, Richard! I felt like I was in your head as both a runner and a writer. It's a wonderful analogy of the landscapes surrounding us, the landscapes within our mind, the need to keep pushing despite the pain or the desire for social media gratification, and the sonic landscapes we have come to love.

While I am not a runner, my wife and I often go for very long walks. Just yesterday, needing a break from my own publication, I went for a 6.5-mile walk. When on my own, I enjoy listening to music while walking. It gives me space to get lost in my thoughts and imagination. I also found it interesting that your piece mentioned Will Oldham, as he embraced the band I, too, wrote about and even released a split 45 and tour-only CD with both artists receiving equal shares of the tracks.

I first came across Callahan via The Flaming Lips, who, between 1986 and 1997, I absolutely adored (was Ronald Jones one of the greatest unsung guitar players of the '90s?). On an EP of theirs from 1994, they covered Callahan's "Chosen One." It inspired me to search him out, and I ended up buying a Smog album. I now own four or five Smog records (my favorite being 'Supper') and have seen Bill live a couple of times.

Richard, your piece on running and the landscape was captivating! The detailed description of your route and the interplay between the natural surroundings and your running experience made it incredibly immersive. Your reflections on music and its intertwining with your journey added a profound layer. The personal anecdotes, especially about rediscovering running with your wife and the memories from your youth, made it heartfelt and relatable. Keep sharing these excellent insights, and best of luck with the Great North Run!