Using Strange Materials: Scattered Thoughts on Lonnie Holley

Words. Matter. Seeds. Objects. Dust.

Words are my matter. I have chipped one stone for thirty years and still it is not done, that image of the thing I cannot see. I cannot finish it and set it free, transformed to energy. —Ursula K. Le Guin, ‘The Mind Is Still’‘I take things and I put them together and then they end up being what humans call art’.

—Lonnie Holley, in The Man Is the Music

Lonnie Holley has a new album out. Tonky. His label Jagjaguwar released it last Friday. While I’m getting to know it, I’ve decided to share notes I’ve been making on Holley’s work over several years, at least as long as I’ve been thinking about my Songs and Objects project. I consider Holley one of my founding inspirations for the project. As a visual artist, he does amazing things with found objects. As a musician, he creates songs that are sometimes baffling, often fascinating objects. Some of those songs map the same territory as the physical objects he makes. All of it maps on to his extraordinary life.

As much as one can say one ‘owns’ art, I have in my collection some reproductions of things Holley has made. I have five LPs of his music, and I’ll say a little more below about why I value these as physical artefacts as well as sonic ones. I’m looking forward to adding Tonky to the collection soon. I have two volumes of the monumental art books Souls Grown Deep: African American Vernacular Art, which contain reproductions of work by Holley and other artists who have been given the descriptors ‘self-taught’, ‘folk’, ‘outsider’ and ‘visionary’. I have various videos of interviews, performances and workshops that Holley has done. Many of these can be found online.

I invariably get the feeling, when I take a Holley collection off the shelf to listen to or look at, that I’m entering a huge world, one that’s too big to take in. This sometimes results in me feeling I can only play one or two sides of a record or look at a handful of images. I get lost in the details of the sounds and visuals and the feel of the packaging. This was already the case when I only had the two Dust-to-Digital albums (from 2012 and 2013) as CDs. It’s even more the case now that I have several Holley LPs. The wordplay leaves me dizzy, or suggests so many ideas to me (it’s very generative); the visuals make me want to go and look at more work by Holley and the other artists included in the Souls Grown Deep archive; the music makes me want to follow up on related musical journeys: Abner Jay, Exuma, Michael Hurley, Nina Simone, Van Morrison, Sun Ra. Holley’s speculative fictions drive me towards writers like Octavia Butler, Samuel Delany and Ursula Le Guin.

Trying to make sense of these trajectories, I’m left with fragments. That’s one reason I describe what I’m sharing here as ‘scattered thoughts’, ideas I’m still in the process of bringing together into something more coherent. There are other reasons for this method. Holley works with fragments, refashioning bits of the world and its history and his life into new shapes. His art invites fragmentary thinking. He often refers to seeds, and I think of seeds as things to scatter (which doesn’t necessarily mean to scatter randomly, but scattering has to start somewhere). Holley is drawn to images and metaphors that highlight potentiality, and I hope my scattered thoughts have the potential to grow or flow into something bigger, something that would grant me the shape of the journey even if I can’t be sure of the destination.

Dust / Matter / Energy

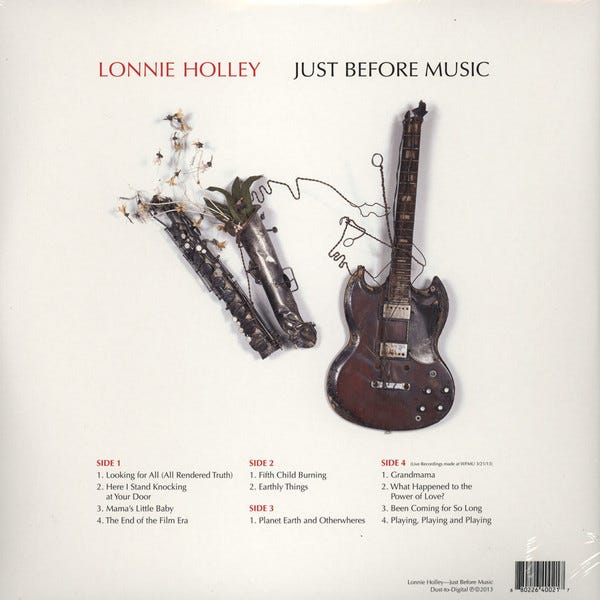

It’s apt that the first label to release Holley’s music was Dust-to-Digital, an imprint whose name and ethos encapsulates the processes of transforming matter and capturing sound. As a follower of the label, I felt I had to check out Just Before Music when they released it in 2012.

What a world to enter.

Holley underlines what the label’s name means for him in the album’s liner notes:

I really wanted to keep DUST TO DIGITAL in my mind making this record. It’s taking from this earth the dust of all the dead. All the wars and all that humans had to deal with has become the dust. The earth is the grave, it’s the biggest graveyard that has ever been. I used to dig graves with my grandma. I was doing the same thing archaeologists have done, but I wasn’t retrieving bones and teeth. I wasn’t doing any research on who this person was, how this human body got there and what kind of life these people lived.

That kind of comparison is typical of Holley. One person digs a hole to put a body in. The body turns to dust and fragments. Another person digs a hole to retrieve the dust and fragments, to make something else from them.

There’s biography here, too, of course, and time travel. I’m not leading with Holley’s biography, though many accounts do. Holley’s life experience, especially his traumatic childhood, is central to his art, but it has been related in many places now and a blow-by-blow account would take up too much space here. This piece from The Fader, published in 2013 between Holley’s two Dust-to-Digital albums, is a good place to start. A longer account by Holley that links his experience to the Souls Grown Deep projects and to other artists, is available here.

I’m interested in Holley’s thoughts on transformation, so here’s a fragment from the Fader piece:

One shouldn’t feel pity for me. I don’t want pity for what I had to go through. I only want humans to hear my testimony and understand that life is not always easy. This is what I’m talking about in my music. My music is not going to be for everybody to hear. Everybody ain’t going to be able to dance and bump and drop it like it’s hot, ease it up like it’s cold. I may not be the best hip-hopper or booty-swapper. There are so many rocks and so many broken stones and so many nails and sticks and weeds and debris and garbage and trash, and we have to plow and mine the worst things on this earth to make them better, and to make us better, so we can show the world: I can handle it. I can deal with it. I can live with it. I can go on. All of this stuff we call hell, how can I take from that hell and make it better?

Holley transforms from gravedigger to archaeologist, taking from the traces he finds in the world to make his art.

We can see him at work in many videos available online. In the one below, which dates from the same period as the Dust-to-Digital albums and the Fader article, we find him offering thoughts on art and transformation at the ATP festival.

Holley discusses the relationships between humans, objects and sounds and the importance he places on ‘keeping a record of it’ (the title of one of his artworks and his second album).

In the first of the film’s two parts, Holley crafts a sandstone sculpture, similar to the kind of thing that got him started as an artist in the late 1970s. At 5:30, he talks about what the material taught him: ‘It taught me an awful lot about the ways of humans, and how our lives are, and how we can be as fragile as these materials that we be involving ourselves with’.

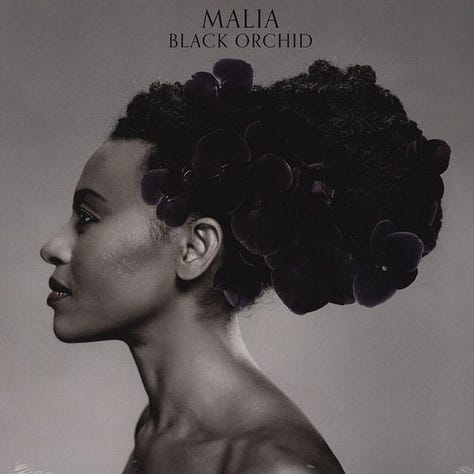

Towards the end of Part 2, Holley takes a black plastic bag and fashions it into a flower-like shape. I’m reminded of the black columbine by origami artist Robert J. Lang that features on Jlin’s Dark Lotus single (misattributed on the record sleeve as ‘Siam’ by Robert J. Lang and Kevin Box; ‘Siam’ is the piece from the cover of Jlin’s Black Origami album, middle image below). I also think about Black Orchid, Malia’s album of Nina Simone songs.

Thinking of Jlin’s ‘black origami’ brings reflections on how sounds are folded up and reshaped in her music, how Jlin, like Holley, brings the experiences and occasional brutalities of manual labour to her work. There’s a set of rabbit holes I’ll step back from for now, about the folding of experience into art by artists, the unfolding done by audiences based on their own experience, about sound as sculpture.

But I will mention dark energy and dark matter briefly. Dark Energy was the title of Jlin’s first album for Planet Mu. It came out a decade ago. Listening to the music, I could hear where that energy was coming from, where it was going, how it was leaping from the vinyl, vibrating the air. Holley’s music doesn’t give off the same kind of kinetic spark (save perhaps a few places on his last album Oh Me Oh My, thanks to producer Jacknife Lee), but it exudes energy. As he put it in the notes to that first album:

ENERGY conquers! Look at our ancestors in the fields, they did it! Up and down the railroads, they did it! Working on the roads, they did it! They did it everywhere! They did it in the churches, they did it in the schools! We had songs with us all the time. Humans had songs even if they weren’t doing anything but moaning, they had MUSIC.

Dark Matter, meanwhile, was the title of a collection of speculative fiction from the African diaspora published a quarter of a century ago. The book’s editor, Sheree R. Thomas, set out the reasons for the title in her introduction:

Long before The Heart of Darkness, the imagination had acted as an instigator of historical change. Africa became the ‘unknown’ and blackness was equated with the ‘Other’. Two hundred years of slavery said so. And as these thoughts became institutionalized and codified, first in the form of slavery and later in the imaginary lines of political maps that documented the scramble for Africa, the people behind the ‘blackness’ receded into the background. They became dark matter, invisible to the naked eye; and yet their influence—their gravitational pull on the world around them—would become undeniable.

Such are the lineages that Lonnie Holley explores in his art.

There is the transformation of matter he undertakes in his physical artefacts, whether carving human heads from lumps of sandstone or creating assemblages from trash he finds lying around.

There is what he does with his music, his unique songs. As Allison Hussey wrote in a Pitchfork review of Holley’s third studio album (and first for Jagjaguwar, in 2018), ‘on MITH, Holley does with music what he’s done with visual art for decades: He collects our ugliest obscured objects and transforms them into singular reflections on our troubled world’.

MITH’s opening track is ‘I’m a Suspect’. It recalls some of the history that Sheree Thomas alluded to—slavery and plantations—but also mentions the hypervisibility of the black subject/suspect in America: ‘listed on all kinds of pages / sometimes appearing to be most wanted’. Holley brilliantly contrasts this visibility with a recognition of the bigger cosmic picture: ‘I’m a suspect in America / but I will end up being a dust speck / out in Mother Universe’.

Being a dust speck in the universe is a reminder that you can’t be out of place (you can’t be the wrong person in the wrong place at the wrong time), that you are one tiny element in a far bigger picture. Reality, however, tells us something else, and Holley pulls no punches in bringing that message home on songs like ‘I Snuck Off the Slave Ship’ and ‘I Woke Up in a Fucked-Up America’.

Before moving on to other matter(s), let me note a comparison between ‘I’m a Suspect’ and another object-oriented epic, Richard Dawson’s ‘Nothing Important’: ‘I am nothing / You are nothing / Nothing important / Death within a dream’.

Water / Testimony / Preaching

‘The Start of a River’s Run (One Drop)’, from Holley’s second Dust-to-Digital album Keeping a Record of It (2013). Song as river, and river as something we are part of the flow of, but also river as something we try to cross. Diachronic and synchronic perspectives on the life course.

Another track, ‘There Was Always Water’, on MITH. Here, water is an essential medium, one which we share and which we might think along similar lines to the way Ashton Crawley discusses air in his book Blackpentecostal Breath. Indeed, given Holley’s early interest in preaching and gospel singing (described in the liner notes to MITH), a reading of Holley via Crawley would be interesting: the aesthetics of breath, speaking in tongues, testimony.

In the liner notes to Keeping a Record of It, Holley describes his listeners as his congregation, and his songs often sound like improvised gospel sermons.

I remember when we used to go to church they had testimony time—time to testify, time to tell the congregation what you had been through. You all are the congregation to me, y’all is the church. My whole life is my testimony, as are the works you’ve seen and heard and the works I’m continuing to do because I can’t stop.

Think, too, of the sermon as object, and of gospel music’s reliance on technological object metaphors: radios, telephones, aeroplanes, spaceships.

See and hear this live 2017 take on the ‘suspect/dust speck’ theme with the duo Nelson Patton (trombonist Dave Nelson and percussionist Marlon Patton) for a good example of the testifying style. At the end, when Holley starts improvising about the seventeenth year of the 21st century, I’m reminded of Exuma’s ‘22nd Century’, another visionary sermon.

Sound / Song / Communication / Archive

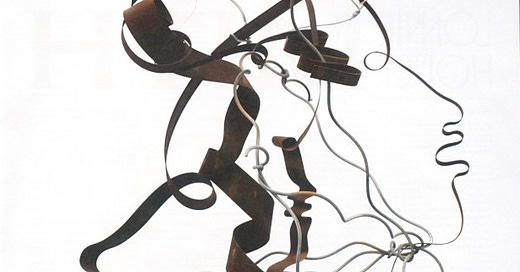

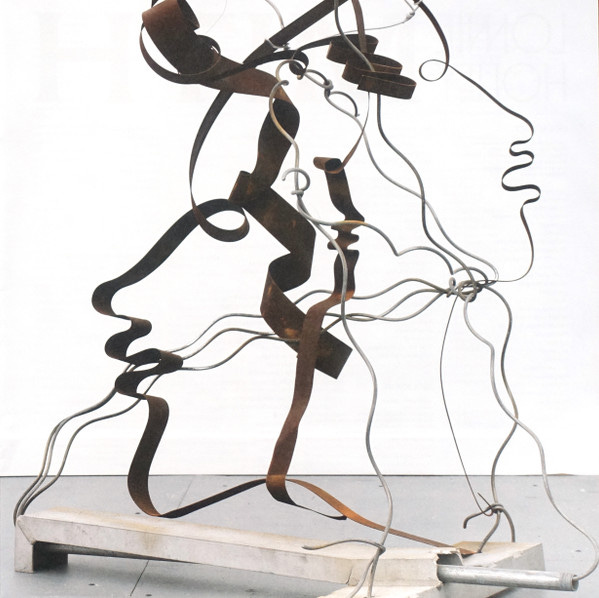

In 1984, Holley created an artwork from burned musical instruments, artificial flowers and wire, which he titled ‘The Music Lives After the Instruments Is Destroyed’. Nearly two decades later, it appeared on the rear sleeve of the Just Before Music LP. When Melchior Huurdeman asked him about it in a conversation for a Dutch art programme, Holley responded, ‘I don’t need an instrument. I’m an instrument’. There’s the sense that, as long as songs have human songholders, they can live on. Yet the art also keeps those dead instruments alive, just as Holley’s records and the videos of his many performances keep his songs fixed in their various forms. It may be the case, as Matt Arnett writes in the liner notes to MITH, that Holley makes songs up on the spot and that no two performances are the same, yet there remains this fixing of so many of them. Records are kept, archives established.

While carving the ear of his sandstone head at the ATP event, Holley says, ‘If I can’t hear you well, can I hear you again? And that’s what I think about keeping a record of it.’ He talks about the need for ‘recommunicating’. ‘Keeping a Record of It’ is the title of his second album and an artwork from 1986 that’s reproduced on the cover of the album. In the album’s liner note, he writes, ‘I make art and I made this record because I think it’s important. It’s important for me to keep a record of my life.’

I’m pleased that Holley, as an improvising artist, is committed to keeping records. He is one of those people who belies the claims sometimes made by improvisors that music must be process and not product. It’s not as if it’s a competition, after all. You don’t remove one of these aspects because you wish to elevate the other. It’s all just matter residing in different forms.

None of which is to forget that all archives, though they promise a rescue from dust, hold within them the threat of return to dust.

Seeds

In his liner notes to Just Before Music, Holley alludes to the idea of sound before music. ‘Did it begin with me sitting somewhere or my ancestors somewhere over in Africa hearing something fall and it thumped HMMMP or someone crawling CHKCHKCHKCHK or hearing a yell AYE AYE AYE? All of these things became JUST BEFORE MUSIC’. In one of the album’s songs, ‘Looking for All (All Rendered Truth’), he sings: ‘Looking for all / All to be rendered / For the truth of human kind / From an internal place in me / From an internal place / That I call “myself”’. Holley makes the term ‘All Rendered Truth’ from the word ART: again, that sense that art will take something that might go unnoticed and render it into some kind of message.

In ‘Earthly Things’, from the same album, Holley wonders what would happen if the things he’s surrounded by, that he has made art from, could judge him. These things bear witness to his life. He also uses the song as a call-out to William Arnett, the man who helped him build his art career. Arnett serves as a witness, helping to bring Holley’s message to the wider world.

Seeds appear frequently in Holley’s songs. Like the river that runs from a single drop, or the dust speck finding its place in the universe, or Holley’s repeated desire for children to be given opportunities that others were denied, seeds are potentialities, symbols of hope but also reminders of what didn’t grow or wasn’t nurtured. As he sings on Keeping a Record of It, ‘we all need sun and water’.

There’s invariably an ecological scope to Holley’s seed imagery. In ‘Planet Earth and Otherwheres’ (on Just Before Music), he sings about ‘Mothers spilling love / Earth all round / Others planting new seeds to grow from the ground / Earthly harvest is plentiful / But the harvesters control with another reality / Control our technology / Computer users / Cell phone abusers’.

In ‘The First Time (So Many Rivers’), from the 2020 album National Freedom, the imagery is biblical: ‘the cradle of human kind’ and a baby in a reed basket ‘floating away from the threats of death’.

Just as rivers flow, seeds blow in the wind. With potentiality comes uncertainty.

Hey, hey can I say where they laid you down Our busy winds scattered you around and sow you like seeds in the wind Over again To a dustly degree And now you are the dust speck of the Universe 'Lonnie Holley, 'Back for Me'

Materiality

It should be clear from the illustrations accompanying these scattered thoughts why I value Lonnie Holley albums as physical artefacts. To engage with one of these discs and its packaging is to enter a world of interconnected sound and text and imagery. Song and album titles shed new light on the paintings and sculptures reproduced on the sleeves, and vice versa. The physical act of playing the record sets artworks into new configurations. Last year, for one of my posts about the art of record labels, I made a video of one of the discs from Keeping a Record of It.

The work reproduced on this label is from 1984, titled Cutting Up Old Film (Don’t Edit the Wrong Thing Out). On the Souls Grown Deep website, the piece is described in terms of its components (film reel and scissors) and a statement from Holley about the importance of letting people tell their own stories. That’s useful context for listening to the 2013 album, but my reason for selecting it for my record label post was the happenstantial translation of film reel to tape spool to spinning vinyl disc.

In his 1986 essay on ‘The Cultural Biography of Things’, anthropologist Igor Kopytoff wrote, ‘Biographies of things can make salient what might otherwise remain obscure.’ I find myself wondering about the biographies of some of the objects Holley has lifted from obscurity. What stories would their pre-art-object existence unearth?

I think here, too, of Michael Thompson’s Rubbish Theory: The Creation and Destruction of Value, a book first published in 1979, the same year Holley was finding his vocation as a sculptor. Thompson’s study of how commodities decrease in value and desirability, only for some of them to become sought after again, is a useful companion text to Kopytoff’s and to the work of anyone who would make new things from old scraps.

Because my thoughts don’t stop, I think also about things in motion, object itineraries, song itineraries.

The things we ignore

A lot of the times, what I was doing would have been totally ignored. And I think they would have stayed ignored if it could have been left up to categorising. Curators and critics, they herded us: outsider artists or artists that is self taught, that is using strange materials, that have no identity in the art world. before I really got an understanding of what this art really meant to the whole of humanity, I used to cry about it. I don’t have a problem with whatever people call me. I’m an artist.

This assertion comes at the end of Maris Curran’s beautiful film about Holley, The Man is the Music. In the film we see Holley visiting his friend and fellow artist Joe Minter at the latter’s ‘African Village in America’. We see him scouring waste ground for objects to use in his art. We see trash piled on the ground, caught in tree branches, stuck in roots and hedgerows. We hear Holley liken the act of liberating it to freeing trapped birds. We hear Holley describe himself as an ‘investigator’, following the clues of his lost and found objects, not in pursuit of who did it so much as on a quest to highlight an ongoing ecological crime.

At one point in the film (5:17), Holley’s commentary moves into the poetic meter of preaching or singing:

Pretty things to me was a shiny piece of glass Pretty things to me was a certain rock Pretty things to me was the roots that had got exposed on the edge of the creeks and the ditches That had got exposed

Curating / Collaborating

I’d been thinking that Holley sometimes reminds me of Abner Jay, so I was interested to see him open a mix for The Fader with a Jay track. There aren’t many people whose mixes or playlists I could imagine myself quoting, but Holley is one of them so here goes:

Abner Jay, "I’m So Depressed" Ben Sollee & Lonnie Holley, "Eskimo Annie" Etta Baker, "Railroad Bill" Alemayehu Eshete, "Ney-Ney Weleba" Bon Iver, "33 'GOD'" Elder Anderson Johnson, "God Don’t Like It" Deerhunter, "Back To The Middle" Jackie Wilson, "Lonely Teardrops" Jerry Butler, "He Don’t Love You (Like I Love You)" Theotis Taylor, "Something Within Me" Lonnie Holley, "I’m A Suspect" Michael Hurley, "Werewolf" Julia Haltigan, "Goodbye Cowboys & Rocketmen" Lonnie Holley, "Looking For All (All Rendered Truth)" Richard Swift, "Selfish Math" Bill Callahan, "One Fine Morning"

Holley always remembers how his work was curated, how, for example, Bill Arnett introduced his work to others. And Holley curates and collaborates: introducing Thornton Dial to Bill Arnett; working with Joe Minter (whose art adorns Holley’s 2023 album Oh Me Oh My and whose voice appears on Tonky); releasing collaborations with the late musician Richard Swift (who also appears in the Fader mix).

March 2015. Tonky.

Early days yet, and I want to get to know the record and not just the digital streams, but the new album seems to bring together many of the familiar strands while sending out new exploratory tendrils.

First song = ‘Seeds’. The seed metaphor is important enough now to get its own song title. The opening lines refer to ‘chasing memories’ and I would say that normally we use this term to refer to voluntary memory, to the things we go looking for in our pasts. But Holley’s using it to talk about the memories that chase us, the involuntary memory: ‘Running after you / trying to capture you / to contain you / to control you / to make you fearful’. This turns into another kind of ‘chasing memory’, of being chased by other people, of the punishments meted out at the Alabama Industrial School for Negro Children, the traumatic childhood scenes that Holley has revisited again and again in his art. Continuity, then, using art to exorcise demons, to turn ugly things into less ugly things, to take seeds and see what can be grown. There’s slavery in this narrative, and fields to be worked, children being beaten, cotton to be harvested: ‘On the one hand it was so white and beautiful / On the other hand you had to pick it and pick it right’.

And a wish that it never had to happen, that the ultimate transformation would be to erase all the trauma and brutality of history, let seeds reach their true potential without hardship.

Oh I wish that I could rob my memory I'd be like Midas and turn my thoughts to gold And one day end up just being alright Where I wouldn't do nothing to lose my soul

The seed reference appears again in ‘Life’, with the idea that energises all Holley’s work like a lifeforce: big and hopeful things can be grown or built from small, insignificant ones. Another track is titled ‘The Burden (I Turned Nothing Into Something’.

All those rotten things that Holley felt should not be left unmarked are recalled in ‘That’s Not Art, That’s Not Music’, which boasts an excellent video by Matt Arnett and Ethan Payne, as well as fine drums and marimba from Budgie (yes, former Slits drummer, Banshee and Creatures co-founder Budgie).

‘The Same Stars’, a track featuring Joe Minter and Open Mike Eagle, picks up on Holley’s previous reflections on slavery and human matter(s). Holley reflects on how the stars we see in the night sky are the same ones glimpsed by enslaved Africans gazing through the wooden boards of the ships transporting them to a new world.

‘Strength of a Song’, featuring Alabaster DePlume on saxophone, is a brief but powerfully moving fragment. Here, it’s the song that holds the subject together, the binding force that heals the broken person or thing.

Two tracks are named after classic soul songs: ‘What’s Going On?’, ‘A Change Is Gonna Come’. The originals would make pretty decent choices if you were going to elect songs whose strength could hold subjects together. Holley’s ‘Change’ contains the line ‘I feel like I’m a leaf on a tree’: changing matter again. The sound design on this track is gorgeous, especially the beat and the gospel vocal that come in just after the spoken section.

The transformation of matter—seeds to trees to leaves to soil-enriching mould—and the transformative possibilities of song, and of hope. It’s not just the change in human relations that’s going to come, which was Sam Cooke’s message. It’s also that we’re all going to change into other matter, dust specks in the universe that will somehow keep Mother Universe alive when transient things such as humanity have disappeared. I’m not saying that’s what Holley is meaning to say—I think he’s too invested in hope for humanity to be focussed on posthumanism here—but it’s what I find myself thinking when listening to this striking collection of songs.

Running the North Tyneside Waggonways yesterday, I passed a tree whose otherwise bare branches held a black plastic bin liner, its wings fluttering in the breeze, its darkness like a crow against the brilliant blue March sky. I thought about black columbines and orchids and dark lotuses, about being trapped and flying free, about the potentialities nesting in every object. I might have thought about some of these things without Holley’s art in my mind, but I wouldn’t have thought about them the same way.

Thank you for this wonderful piece, Richard. I was out of the country with dodgy internet and am just now catching up on some bookmarked articles. It is so nice for Holley to be receiving this attention, and I am happy you are sharing his art and music (what a voice!) with your audience. You should also share your piece with him!