These Foolish Things Part 2: Songs as Objects

To trace these trajectories is to be aware of what blossoms out of a simple organism, a song-seed, to think of the song itself as an evocative object.

Songs as objects

One aim of my Songs and Objects project is to explore a range of musical examples from the last hundred years of popular song and focus in detail on singers and songwriters who’ve shown an interest in using objects in their songcraft. But I also want to extend this analysis to consider songs themselves as objects that are created, shared and cherished, becoming things by which listeners map experiences and memories. I want to ask what kind of object the song object is and how song objects relate to the things they depict.

In writing about ‘These Foolish Things’, I used the song as an example of how objects can be lined up in songs to do evocative memory work. The song is also a good example of an object in and of itself. As a standard, it has been recorded countless times, meaning that we have available to us all manner of ways to perform the song. Most of these make big or small changes to the song content, instrumental flavour or performance style while still retaining what the singer-songwriter Will Oldham calls ‘the bones of the song’. This is one way to think of songs as objects: things with structure, form and content that retain a high level of consistency even as elements are changed. Here, what remains constant (or at least recognisable) is what constitutes the song’s objectness.

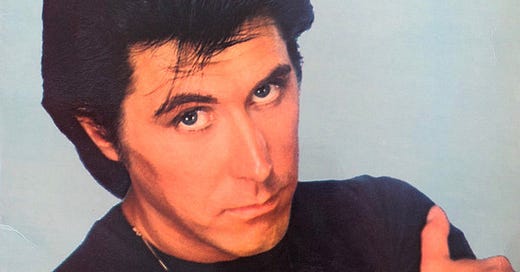

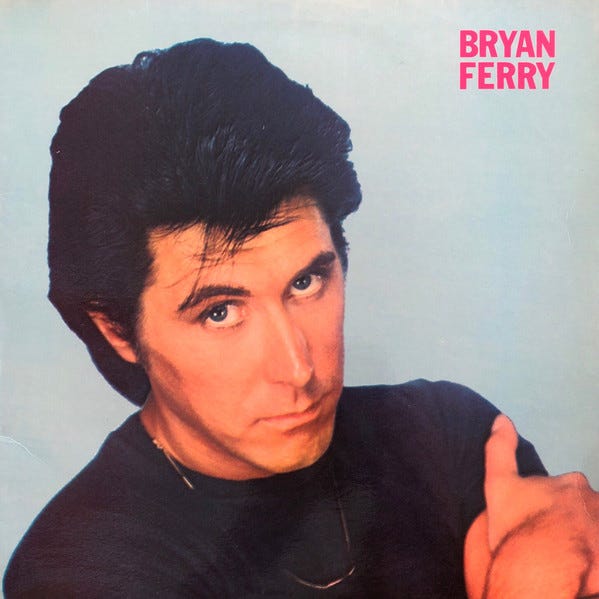

Another way that songs get referred to as objects or things is through their role as technologies of memory, bundles of stuff that may often seem inconsequential but gather great evocative importance when fused with personal and collective experiences and memories. This way of thinking is signalled when Bryan Ferry names his 1973 covers album These Foolish Things, the title doubling up as a reference to this specific song and to all the other songs contained within.

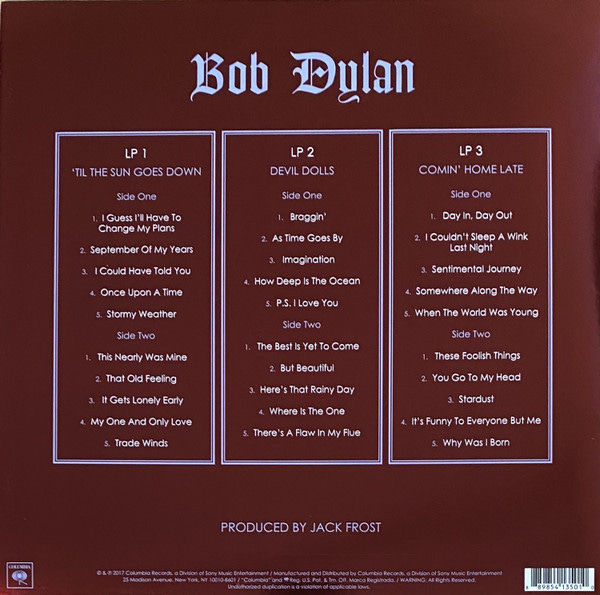

Others have made similar connections. In his liner notes to Triplicate, a collection of standards released by Bob Dylan in 2017 (and which includes a version of ‘These Foolish Things’), Tom Piazza refers to the reflective tone with which Dylan approaches the songs: ‘the angle of light’, Piazza writes, ‘is mostly autumnal; the songs address longing for something gone, or just out of reach, a past that can’t be retrieved, the foolish things that remind you of love and loss’.

Appearing the same year as Triplicate, Will Friedwald’s book The Great Jazz and Pop Vocal Albums contains an introduction in which the author discusses the new possibilities of the album format. Writing about Frank Sinatra’s pioneering 1945 album The Voice, Friedwald notes the aptness of its opening song as follows:

Fully titled, “These Foolish Things (Remind Me of You)” is a perfect song for the first-ever real pop song album, since it not only was a song that most people would have known in 1945, but the song itself is a kind of album of memory, a catalogue of the inconsequential bric-a-brac and folderol that accumulate during a relationship … Fittingly, some of the “things” are musical, like “the waiter whistling as the last bar closes” and “a tinkling piano in the next apartment” and, most tellingly, “the song that Crosby sings”. The lyrics are a prescient illustration of what the pop song album would become; not one of the foolish things is significant in itself, but they add up to a vivid story, much the way that the eight individual songs on The Voice add up to a narrative.

I don’t believe Friedwald means to suggest that songs are inconsequential anymore than Ferry does, though I would agree that albums offered a new way of thinking about songs, just as mixtapes and playlists would later. As with my own use of the term ‘foolish things’ as a way to talk about songs as objects as well as objects in songs, Ferry and Friedwald playfully respond to pop’s perceived lack of seriousness by taking the songs very seriously indeed.

Ian Penman touches on something like this when, in a brilliant essay on Frank Sinatra, he alights on what Sinatra does with the words he sings:

Listen to how he strings out the word “ordinary” in the line “the little ordinary things”, thereby making it far from ordinary. Then with the line “the mere idea of you” he draws out the word “mere” as though it were the sweetest qualifier in the world: dissolving “mere” into “idea” he makes the very idea of “mere” sound transcendent.

And, in a killer line about the album these songs come from (1962’s Sinatra Sings Great Songs from Great Britain), Penman writes, ‘Sinatra takes £5 words and makes them glisten like mystic opals. his voice like spring light clarifying a dusty catacomb’.

I like to think of Bryan Ferry working in a tradition that Will Friedwald has Sinatra and his record label initiating (the potential of the ‘pop song album’). We might equally think of Ferry as the first ‘critic’ to make explicit the connection between objects in songs and songs-as-objects. I mention this to emphasise a parallel I’ve already hinted at, between the interpretative work of singers and that of critics and scholars. Music criticism and scholarship, after all, are often about highlighting apparently small things and exploring the multitude of meanings that can be found in the seemingly mundane.

When I say ‘scholarship’, I’m not limiting that to those who work in educational institutions as academics, but also thinking of those who—having been called to song through fascination, seduction or obsession—undertake to explore and explain its wonders and variations.

Versions

One way to think about this in relation to ‘These Foolish Things’ is to consider all those multiple versions. How do we count, and account for, their similarities and their differences? We could create a biography of the song, as Robert Cushman does in his contribution to Lives of the Great Songs. We could build a database, website or other resource to catalogue the sometimes minute differences between versions of this and other songs, perhaps basing using the valuable resources at SecondHandSongs as a starting point. We could join the conversation as online commentators (see, for example, Jim Radcliff’s Songbook posts or the detailed account of ‘These Foolish Things’ at Cafe Songbook).

Cover versions constitute another kind of study, an interpretation of what a song means. Praising Dylan’s covers of Sinatra standards, Tom Piazza claims that the singer’s ‘mastery is deployed to bring out the real meaning in the lyrics’. We might question what is meant by ‘real’ here; presumably what is real for me might be different to what is real for you. But we can still get Piazza’s general point. What I’m more interested in here is how this same phrase might be written about a particularly good music writer. Singing, like music criticism, can be exegesis.

To trace these trajectories is to be aware of what blossoms out of a simple organism, a song-seed, to think of the song itself as an evocative object. In his biography of ‘These Foolish Things’, Robert Cushman writes that this and another Maschwitz hit, ‘A Nightingale Sang in Berkeley Square’, ‘have become nostalgic shorthand for old Mayfair’. Then he adds some evocative shorthand of his own: ‘Angels dining at the Ritz, and candle-lights on little corner tables: the debutante-and guardsman set succumbing decorously to passion or, when it’s over, keeping a stiff but remarkably loquacious upper lip’.

At the close of Twelfth Night, Shakespeare has the fool Feste sing a song which makes reference to a toy as ‘a foolish thing’, and with it the idea of childhood play and tomfoolery is presented as something both longingly missed and yet, in the figure of Feste and in the refrain of the song itself, cherished and maintained in the affirmative present. Such is the way Mark Booth reads the example in his wonderful book The Experience of Songs, opening and closing his wide-ranging introduction with the example of Feste’s song.

The notion of the song as itself a ‘foolish thing’ is underlined by some of the Twelfth Night commentary quoted by Booth; the song was described by Shakespeare critic Edward Capell in the eighteenth century as ‘a thing idly drop’d from [Shakespeare] upon some other occasion’ , while other critics felt it a gimmick not worthy of the playwright. But Booth suggests that this is a misreading of what song is and does. We shouldn’t hear Feste’s words as communicating a typically Shakespearian wisdom, but rather as the kind of communication, or ‘pseudocommunication’, that song entails. The song, in Booth’s words,

is not set up by its author as a story to be read, or packaged as a message from Shakespeare or Feste to the audience. Given music, the words are given the status music can give to words: when the clown songs them, he sings not to but for the audience. he tells them nothing they need to decode and learn. He evokes in them one of the ways of seeing life that they already have.

I agree with Booth’s description of what songs communicate and with this idea that songs tell us things we already know, but perhaps have not yet articulated or had articulated for us. Songs fix things for us, by which I mean both that they hold things in place at least for a while and that they heal us. They may also hurt us, or recall hurt for us. The materiality of song allows for the possibility of songs being things we live with, memories we relive and lessons we live by.

Songs as knowledge

A song offers the promise of something that can survive across time, that can take on its own life force or vitality. Songs are forms of knowledge; they are also objects which invite us to build knowledge about them and around them. One way to consider this is to ask how one goes about finding out about a song. How might we increase our knowledge of ‘These Foolish Things’?

There are resources such as Wikipedia, of course, which can tell us much about the song’s composition, its life in recordings and its career in other media (for example, its use in films, television talent shows, live performances, and so on). Then there’s YouTube, where multiple versions can be found, from commercial recordings acquired elsewhere to amateur renditions made solely for YouTube. At least one helpful user has compiled a list of YouTube renditions of ‘These Foolish Things’ in one place, giving easy access to versions covering several decades.

There are also music streaming services such as Spotify where users can arrange a list of versions of a song and add them all to their own playlist. Provided I have access to the Internet, these are all easy-access options for amassing a lot of information about ‘These Foolish Things’, or any other song. Given enough time, resources and inclination, I could pursue the song further by following up on the text sources cited in Wikipedia and checking out other online links, or perhaps by purchasing physical copies of the various recordings.

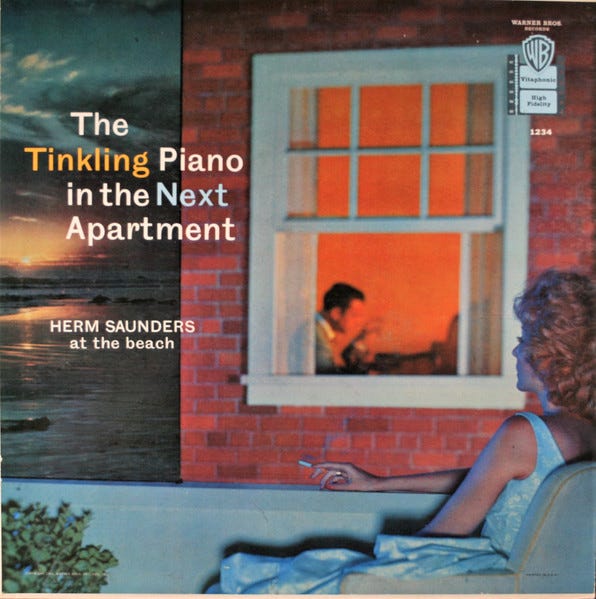

Perhaps I could attempt to get at the innards of the song through some form of technical analysis or through a musical performance of my own. If I were feeling creative, I might line some of these up alongside representations of the objects listed in the song. Did Merv Griffin and Herm Saunders have something like this in mind when they both released albums titled after a line from ‘These Foolish Things’?

And what are the songs being played on the tinkling piano? One of them, of course, has to be ‘These Foolish Things’; it’s the first track on Griffin’s and Saunders’ albums.

No matter how far I went with my pursuit of ‘These Foolish Things’, I would never exhaust the song, nor the various objects with which it evokes. Some foolish remainder, some ghost, would always be lingering out of sight, earshot or grasp. Perhaps it would be a foolish exercise, but perhaps such activities could also tell us something about songs or objects, or both. By tracing connections, following routes, being willing to zoom in and out and travel between and through and along the inner and outer world of songs, we might learn something new, or at least have our fascination with songs revived and made refreshingly strange.

Where might song take us next?

The text above is a slightly revised extract from the first episode of the Songs and Objects podcast, originally released in August 2021. I’ve divided the episode in half for this version. The first part discusses songs that use objects as lyrical devices.

References and further reading

Will Oldham, Will Oldham on Bonnie ‘Prince’ Billy, ed. Alan Licht (London: Faber & Faber, 2012).

Tom Piazza, liner notes to Bob Dylan, Triplicate, LP, Columbia 88985413511, 2017.

Will Friedwald, The Great Jazz and Pop Vocal Albums (New York: Pantheon, 2017).

Ian Penman, It Gets Me Home, This Curving Track (London, United Kingdom: Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2019).

Tim De Lisle, Lives of the Great Songs (London: Penguin Books, 1995).

Mark W. Booth, The Experience of Songs (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1981).