Songs About Musicians #2: Protest Singers

Guthrie, Dylan, Jara, Ochs, Bragg, Kristofferson, O'Connor. But who's singing about whom?

This second post in my ‘Songs About Musicians’ series focusses on songs that have been written about protest singers. The singers and songwriters featured here—both the honourers and the honourees—are musicians who have been part of my listening life for decades. They form part of my musical unconscious, and I’m therefore not surprised that the idea for this particular topic came to me early on when thinking of songs about musicians.

While I think the term ‘protest singer’ feels intuitively right for the artists mentioned below, I also feel it can be reductive. Phil Ochs, one of my featured song subjects, reportedly preferred the term ‘topical’ to ‘protest’, and there’s something to be said for that. My reservation is less a definitional one, though; it’s more that, while there are undoubtedly such things as protest and/or topical songs, there aren’t many singers who can be identified with those alone. The artists featured here had wide repertories, which included but weren’t restricted to protest or topical material. I’d urge anyone who is unfamiliar with them to seek out that wider work.

I’m sticking with the protest singer designation because it feels like a good reason why someone would have songs written about them. Many protest or topical songs are about individuals who embodied something that others might respect, aspire to or feel motivated by (there are also, of course, many songs that target individuals who are reviled rather than revered). It makes sense that the singers who immortalized folk heroes should receive similar treatment.

The subjects of these songs are all dead, though only two of them were when the songs were written. There are other connections between the artists mentioned here, some of which I tease out in what follows and some I leave to be revealed as when time and suggestion send curious minds down particular rabbit holes.

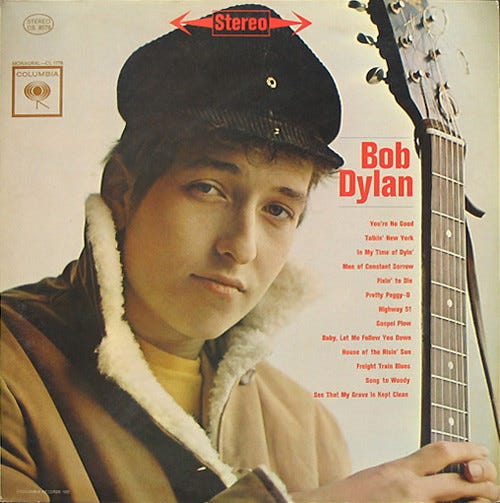

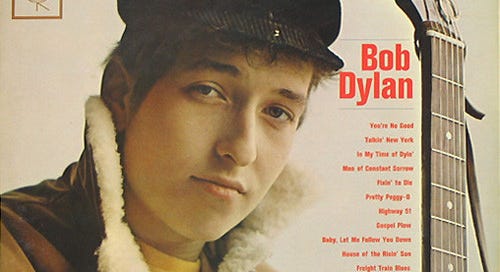

Bob Dylan, ‘Song to Woody’

Written by: Bob Dylan

From: Bob Dylan (Columbia, 1962)

James Mangold’s A Complete Unknown has brought renewed attention to the early years of Bob Dylan’s career, the period in the early 1960s where he arrived in New York and made his name as a singer and songwriter. I haven’t yet seen the film, but I understand that it includes a scene where Dylan performs his ‘Song to Woody’ to the hospitalized Woody Guthrie. I’ve also heard Timothée Chalamet’s performance of the song from the movie soundtrack.

Dylan’s devotion to Woody Guthrie (1912-1967) has been well documented over the years. Guthrie’s singing and guitar styles were among the prominent features of Dylan’s early performances and ‘Song to Woody’ is appropriately Guthriesque in its form, lyrical content and vocal register. What it doesn’t do is provide an account of Guthrie’s many topical or protest songs or portray Guthrie as the musical campaigner he was. Instead, Dylan opts to focus on Guthrie as a man on the move, the rambling, hard travelling hobo that Guthrie detailed in many of his songs and in his memoir, Bound for Glory.

The opening verse:

I’m out here a thousand miles from my home Walkin’ a road other men have gone down I’m seein’ your world of people and things Your paupers and peasants and princes and kings

Note that early use of Dylan’s list song technique in the fourth line, which is echoed later in the song’s mention of ‘Cisco an’ Sonny an’ Lead Belly too / An’ to all the good people that travelled with you’. Those fellow travellers—Cisco Houston, Sonny Terry and Huddie Ledbetter—also provide an early example of Dylan placing musical references in his lyrics, something he’s done throughout his career.

Paul Williams, always one of my favourite sources for Dylan analysis, has the following to say in Bob Dylan: Performing Artist 1960-1973:

I like what ‘Song to Woody’ says about Dylan’s experience. It speaks of a person inspired to walk in someone else’s footsteps, and discovering a world of his own—the world, the real world that’s out there—as a result. It speaks of the longing that Dylan’s appreciation of Guthrie sets up in him—a longing to speak to and have something to say to the person who has spoken so powerfully to him. It’s a song from the heart, and it communicates humility, true humility not pose—it’s a song full of childlike wonder and love. And it’s a good example of how the proper setting, in terms of melody and arrangement and vocal and instrumental performance, can transform an adequate set of words into a truly memorable song.

I, in turn, like what Williams’ account of ‘Song to Woody’ says about the tangled forms that innocence and experience can take in popular song. That sense of childlike wonder—something I noted, by the way, in the first ‘Songs About Musicians’ post, on Laura Veirs—sits in fascinating tension with the air of experience that Dylan tries to project on his early recordings. This is all part of what I’ve previously called Dylan’s ‘poetics of place and displacement’: tensions between home and away, movement and stasis, innocence and experience.

Guthrie proved to be an early and influential model of such tensions for Dylan and it feels appropriate that these were the qualities the young singer highlighted on one of only two self-written pieces on his debut album. Guthrie’s status as a protest singer, meanwhile, is implied rather than explicitly stated in Dylan’s homage; it’s there in the references to Guthrie’s life experience: ‘I know that you know’ and ‘there’s not many men that done the things that you’ve done’.

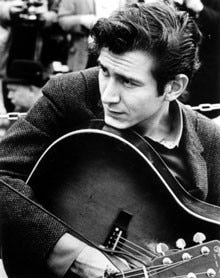

Woody Guthrie sang about many folk heroes, from John Henry and Jesse James to Pretty Boy Floyd and Tom Joad. Later singers were bound to honour him, either by covering his songs or writing their own about him. Dylan’s virtuosic poem ‘Last Thoughts on Woody Guthrie’ shows the young singer-poet emerging from Guthrie’s shadow to develop his own pop collage language. Phil Ochs’ ‘Bound for Glory’ deals with the misappropriation of Guthrie’s work. Alabama 3’s ‘Woody Guthrie’ is not about the singer but connects his name to observations about contemporary socio-political issues. Steve Earle’s ‘Christmas in Washington’, addressed to Guthrie, yearns for the singer’s reincarnation alongside Emma Goldman, Joe Hill, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King. The British folk singer-songwriter Reg Meuross, a writer of many songs about folk heroes and villains, has a forthcoming album about Guthrie based on a commission by Pete Townshend. Fire & Dust: The Woody Guthrie Story is, according to Meuross’ Bandcamp site, ‘a journey into the heart and soul of one of America’s finest folk musicians’. Three singles have been released so far, the latest being ‘Woody Guthrie’s Chains’.

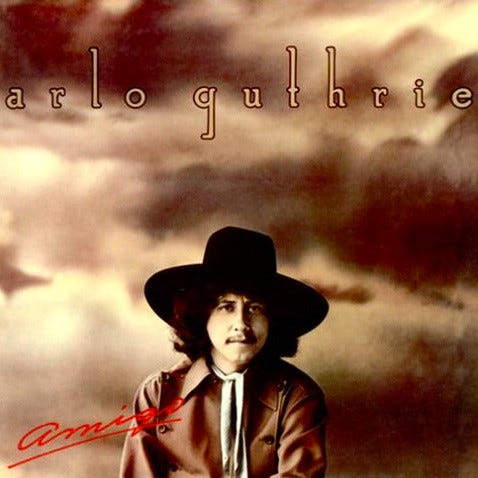

Arlo Guthrie, ‘Víctor Jara’

Written by: Adrian Mitchell (words) and Arlo Guthrie (music)

From: Amigo (Reprise, 1976)

Woody Guthrie’s fifth child Arlo is probably best remembered today for his epic 1967 song ‘Alice’s Restaurant’, which remains a US radio staple at Thanksgiving. He also has a long career behind him defined by protest songs, campaigns and collaborations with other musicians, notably Pete Seeger. In 1976, Guthrie released the album Amigo, which contained a song honouring the murdered Chilean folk singer Víctor Jara.

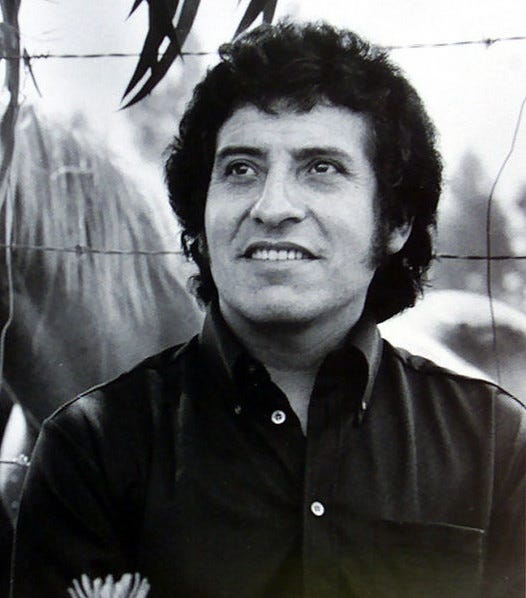

Jara was a cantautor (singer-songwriter), performer, theatre director and political activist. He was a major force in the nueva canción chilena (New Chilean Song) movement, along with Violetta Parra, her children Isabel and Ángel, and the groups Inti-Illimani and Quilapayún. Having already released several records in the 1960s, Jara became a prominent voice in the campaign that brought Salvador Allende’s Unidad Popular party to power in the 1970 Chilean elections. Because of his political affiliations and his perceived influence on the population, Jara was arrested by the Chilean forces following the military coup of 11 September 1973 that overthrew the Allende government. Along with thousands of others, he was detained in a stadium in Santiago. There he was tortured and murdered.

With the deaths of Allende, Jara and poet Pablo Neruda within days of each other in September 1973, Chile lost three iconic figures. Yet this was only the beginning of the silence that was to come. There followed the burning of nueva canción recordings, the silencing of indigenous instruments associated with the music, and the exile of many notable musicians, such as Inti-Illimani, Quilapayún, Isabel and Angel Parra and Patricio Manns.1

By 1974, an international solidarity movement was working on ways to keep alive the legacy of all that had been lost in the coup. In London, this included Jara’s widow Joan and the poet Adrian Mitchell, who wrote the lines that Arlo Guthrie would set to music.

‘Víctor Jara’ traces the singer’s life from his rural upbringing through to his songwriting, campaigning and murder. The song’s refrain focusses on his hands, ‘gentle’ and ‘strong’. This helps to remind listeners of Jara’s role as musician, but there’s a more sinister undercurrent. By the time Mitchell wrote the poem, stories had emerged from the Santiago stadium that told of Jara’s fingers being broken, of him being taunted by military guards who told him to try playing his guitar with his maimed hands.

Guthrie can be heard performing an early version of the song, with piano accompaniment, in a recording of a benefit concert that took place in May 1974 in New York. The event, titled ‘An Evening with Salvador Allende’, was organised by the singer Phil Ochs and the Friends of Chile. It included performances by Ochs, Guthrie, Bob Dylan, Pete Seeger, Dave Van Ronk, Dennis Hopper, Mike Love and Melanie, as well as film screenings and readings. This rendition of ‘Victor Jara’ includes Mitchell’s final verse, which didn’t make it to the later album version, with lines highlighting the UK’s role in supporting the Chilean generals: ‘they rule with Hawker Hunters and they rule with Chieftain tanks’.

Mitchell and Guthrie’s song has also been recorded by Christy Moore, Arthur Johnstone, Dick Gaughan and Alistair Hulett, among others. The version that Gaughan includes on his Live in Edinburgh album from 1985 has the verse about the Hawker Hunters and Chieftain tanks, as does Alistair Hulett’s reading of the song on his album In the Back Streets of Paradise (1994). Hulett’s is probably my favourite delivery of the song, partly due to his Gaughanesque phrasing. The performance in the video below is close to the album version and also features Jimmy Gregory.

Other songs about Víctor Jara include ‘Canción Para Víctor Jara’ by Quilapayún, ‘Canción a Víctor’ by Inti-Illimani, ‘Victor Jara’ by Hoola Bandoola Band, ‘Victor Jara’s Hands’ by Calexico, ‘Cân Victor Jara’ by Dafydd Iwan, and ‘Ode to Victor Jara’ by The Melodic. There are many songs that mention Jara, such as ‘Washington Bullets’ by The Clash, ‘One Tree Hill’ by U2, and ‘Chile Your Waters Run Red Through Soweto’, by Sweet Honey in the Rock, also recorded by Billy Bragg. Even in Exile is a concept album by James Dean Bradfield based on Jara’s life, released in 2020.

Billy Bragg, ‘I Dreamed I Saw Phil Ochs Last Night’

Written by: Billy Bragg (words) and Earl Robinson (music)

From: The Internationale (Utility, 1990)

This song by Billy Bragg is from the EP or mini-album The Internationale, released between the full-lengths Workers Playtime (1988) and Don’t Try This at Home (1991). A celebration of the American ‘topical singer’ Phil Ochs (1940-1976), it’s based on Alfred Hayes’ poem ‘Joe Hill’, which was set to music in 1936 by Earl Robinson and performed by many folk and protest singers. Paul Robeson included ‘Joe Hill’ on his 1943 album Songs for Free Men, Joan Baez on her 1970 release One Day at a Time. Ochs himself reportedly performed it, though he also had his own song about Hill, which he recorded for his 1968 album Tape from California.

Bob Dylan adapted the opening lines of Hayes’ poem for his ‘I Dreamed I Saw St Augustine’, on John Wesley Harding. This was the song I thought of when I first heard Bragg’s song about Ochs, partly because I was more familiar with ‘St. Augustine’ than ‘Joe Hill’ and partly because Bragg mentions Dylan in his liner notes, which I quote here for further context on Bragg’s song.

‘New’ Bob Dylans were ten a penny in the late sixties but there was only ever one Phil Ochs. Both artists came out of the same Greenwich Village protest music scene but when Dylan became a rock star in 1966, Phil stayed true to the political tradition of Woody Guthrie, Campaigning against the Vietnam War he was arrested at the Democratic Convention in Chicago in 1968 and he sang with Victor Jara in Chile in the early seventies. When he died in 1976 his FBI file was 410 pages long. America has yet to produce another songwriter like him.

That briefly sums up a life which can be explored in more detail in various books about Ochs (including works by Marc Eliot, Michael Schumacher and Jim Bowers), as well as Kenneth Bowser’s documentary There But for Fortune. I’d also direct interested readers to a recent Substack post about Ochs and Dylan by Russ Burlingame, which I discovered while trying to find out whether Ochs featured in the Dylan biopic (it turns out he doesn’t).

As Burlingame notes, discussions about Ochs tend to include a hefty amount on his relationship with Dylan. Bragg’s liner notes gestures that way, but his short song focuses on Ochs’ fraught relationship with the music business, his refusal to compromise, the scrutiny he received from the FBI, and Bragg’s appreciation for the lasting legacy and inspiration that Ochs’ music provides.

As Bragg mentions in his liner note, there’s a connection with Víctor Jara too. Inspired by Allende’s reform programme, Ochs travelled to Chile in 1971, where he met Jara. Accounts of how this came about differ—for example, in Joan Jara’s Victor: An Unfinished Song and Marc Eliot’s Phil Ochs: Death of a Rebel—but the outcome is the same: Jara taking Ochs with him to perform for Chilean miners in the Andes.

The deaths of Allende and Jara affected Ochs badly. Nevertheless, he worked with the Friends of Chile to organise the aforementioned Madison Square Garden event, ‘An Evening with Salvador Allende’, in 1974. During the concert he recalled his friendship with Jara. Listening to the recording of the event, you sense again that particular kind of international solidarity that musical communities often aspire to. Bragg’s song, as with so much else from his career, adds another element to that ongoing story.

Hear also: ‘Phil Ochs’ by Latin Quarter, ‘Phil Ochs’ by Josh Joplin Group, ‘Phil Ochs, Bob Dylan, Steve Goodman, David Blue and Me’ by John Wesley Harding, ‘The Parade’s Still Passing By’ by Harry Chapin, ‘Radio Fragile’ by Nanci Griffith, ‘Thin Wild Mercury’ by Peter Cooper and Todd Snider, and ‘Phil Ochs & Elvis Eating Lunch in Morrisons Cafe’ by Reg Meuross. Will Oldham’s ‘Gezundheit’ starts out sounding like a cover of ‘I Dreamed I Saw Phil Ochs Last Night’, before moving into something quite different: a curiosity.

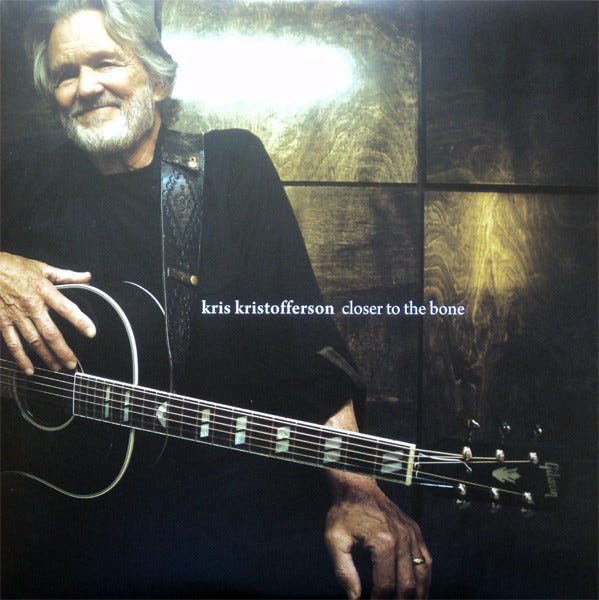

Kris Kristofferson, ‘Sister Sinead’

Written by: Kris Kristofferson

From Closer to the Bone (New West, 2009)

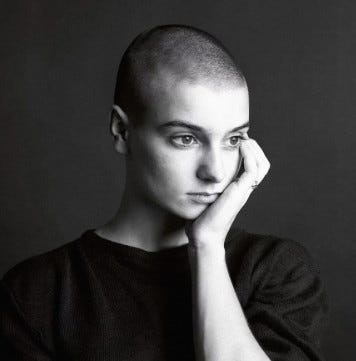

Sinéad O'Connor (1966-2023) is the most recent song subject of the four I’m featuring here. She was alive when this song was written; now, she’s gone, and so is the man who wrote the song.

There’s another Bob Dylan connection here, a Madison Square Garden one too. It was at a Dylan tribute concert at MSG in 1992 that O’Connor stood her ground against a hostile crowd. The reason for the hostility is well-known: the then-recent incident on Saturday Night Live when she tore up a photo of Pope John Paul II while performing Bob Marley’s ‘War’. At the Dylan event, scheduled to offer a reading of ‘I Believe in You’—which would have sounded something like this—O’Connor, faced with the crowd’s relentless booing, shut down her band, removed her earpiece and launched into ‘War’ instead.

David Honigmann provides an excellent write-up, in a 2016 article for the Financial Times, of what happened when O’Connor ‘switched Bobs, from Dylan to Marley’. ‘The most Dylanesque moment of the night’, he observes, ‘is not even Dylan’.

O’Connor wrote about her longstanding Dylan fandom in her memoir and frequently mentioned him in interviews. In a June 2021 interview with ABC’s The View, she said ‘everyone wanted me to be a pop star, and I felt I was a protest singer, one of the children, one of the millions of children, of Bob Dylan and John Lennon’.

That’s how Kris Kristofferson treats her in ‘Sister Sinead’. It was Kristofferson, of course, who went out on stage while O’Connor stood facing that New York crowd, who told her not to let the bastards get her down, who offered an arm and shoulder after she’d delivered her version of Marley’s message, who wrote a song for her like other songwriters had written songs for other protest singers.

It's asking for trouble to stick out your neck In terms of a target, a big silhouette But some candles flicker and some candles fade And some burn as true as my sister, Sinead

Unlike the other protest singers featured here, I’m not aware of many songs written about O’Connor, but there is ‘Sinead’ by Jim Page.

As I did with the first ‘Songs About Musicians’ post, I’ll close with some music by each of this week’s subjects. If any readers have any favourites by these artists, I’d love to hear about them in the comments.

First off, here’s Woody Guthrie singing ‘I Ain’t Got No Home in This World Anymore’. Given current events, I was planning to share ‘Deportee’, but that was a Guthrie poem that other singers recorded (Cisco Houston, Joan Baez, my personal favourite Rory McLeod, among many more), so I’ve chosen a related song.

Víctor Jara, ‘El Derecho de Vivir en Paz’ (The Right to Live in Peace). This clip is from a Peruvian television programme in which Jara spoke about and performed several songs. There are two in this clip, but it should start at the second song, minus the introduction (if not, jump to 6:05).

Phil Ochs, ‘There But for Fortune’. Not the most protesting of Ochs’ songs. Timeless rather than topical, unless those words are thought of as synonyms. They’re usually not, but timeless songs must always be of this moment as much as of others.

Sinéad O'Connor, ‘Fire on Babylon’. A song about lies, manipulation and abuse.

Some of this text is adapted from an article I wrote nearly two decades ago when I was a PhD student: ‘Reconstructing the Event: Spectres of Terror in Chilean Performance’, British Postgraduate Musicology 8 (2006). It’s available here. I go into more detail about Jara and nueva canción in a chapter of my PhD thesis; I’m happy to share details of that with anyone who’s interested, though I recognise that there has been a considerable amount of fresh research on this topic since I wrote about it.

Hi Richard, nice piece as always. I've been listening a lot to Burning Spear recently, which drew me back to Sinead's Throw Down Your Arms. It's my favourite album of hers, actually.

As for Ochs, - and it might be an obvious choice - but the track 'Pleasures of the Harbor' gets me every time I hear it. There is also an acoustic version of 'Crucifixion' I have on a box set of his - 'Farewells & Fantasies' if memory serves - which is also another terrific performance.

TBH, I'm no longer in sync with the overt politicking of the likes of Bragg, but 'The Man in The Iron Mask' and 'The Saturday Boy' are tops.

And I still have a lot of time for Rory, I'd say my favourite album is Mouth to Mouth, 'Hunger is the Best Sauce' - lip smacking fun!

All the best. Martin

Great post, Richard. I've just purchased Sinead's autobiography and am looking forward to reading it, especially after what you've said here. I should add that I just finished reading a biography of Janis Joplin and Kristofferson was a big fan, friend, and supporter of her as well.