Riding the Blue Wind: Townes Van Zandt's Fatalism

'Nashville's just not geared for minor keys'

The Texas singer-songwriter Townes Van Zandt was born on 7 March 1944 and died on 1 January 1997. In the week of what would have been his eightieth birthday, I’m posting texts inspired by his songs and performances. Townes quickly became one of my favourite musicians when I discovered his work in the late 1980s. These pieces amount to my first tentative explorations of a body of work I’ve been returning to for more than three decades.

I originally planned for this post to appear on 7 March, but fate had other plans. The week dealt me a strange set of cards that forced me to change my writing plans. Then the piece itself took on a leggier form and I decided to follow it where it wanted to travel. I also decided not to split or cut what I’d written, and I therefore beg the reader’s forgiveness for the lack of brevity here.

What follows emerged from me thinking about how I might try and categorise Townes’ songs and what messages they communicate to me. In thinking about this music as communication of experience, I wanted to think about the kinds of songs Townes wrote and the voices he employed. When I say ‘voice’ here, I mean not only the singing voice, but the voice of the songwriter that comes through the lyrics and music.

I’ve been writing a lot recently about music as sounded experience. My last post was an attempt to communicate some of my feelings about first encountering, and then living with and learning from, the music of Townes Van Zandt. Weirdly, perhaps, I found the best way for me to do that was to not give any specific details about Townes or his music.

This piece starts to fill the gaps I left, though I won’t be focussing here on biography. There’s plenty of biographical information about Townes and those close to him to be found online and in print. I recommend the book-length biographies by John Kruth and Robert Hardy in combination with Margaret Brown’s documentary Be Here to Love Me.

Though I’ve often been drawn to reading about Townes’s life, I’ve never felt the desire to map his biography to his lyrics. I’m in broad agreement with Ann Norton Holbrook when, at the start of a deep scholarly dive into how gender plays out in Townes’s songs, she writes that, rather than using an autobiographical voice, he ‘assumes an indefinite persona for philosophical musing, employing universal rather than private terms and symbols’.

If I’m not looking for biographical mapping, neither am I looking for a set of definitive messages or lessons that can be taken from the work. I’m guided more by what kind of experience I felt I was hearing in Townes’ music when it arrived in my life. How clear or explicit was the experience being communicated? Was it more like accumulation or accretion, something that’s hard to pin down but still tangible, something you wake up one day to find you’ve got, though you can’t tell quite where it came from?

There’s something to say here about conviction, too. I may not feel the need to pin Van Zandt’s life experiences to specific lyrics, but, like any listener to this kind of material, I guess I do want to be convinced that the singer is sharing some kind of truth or insight with me, communicating some form of experience, however intangible.

Part of that is lyrics, part is musicianship and part is performance style. And voice, of course. Voice has always been vital for me. I can’t believe a singer if I can’t believe their voice. Listening again this past February to Van Zandt’s second studio album, Our Mother the Mountain from 1968, I found myself thinking how much I enjoyed sinking into that voice, trusting myself to it.

There needs to be a willingness to hand responsibility and care to a singer. I recall how, over the years, I’ve become accustomed to reading accounts about Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen—and sometimes Townes Van Zandt—that claimed their voices weren’t the ideal vehicles for delivering their songs, that other singers’ renditions did them more justice. I’ve never bought that line, and Townes’ has always been the voice I want to hear singing his songs.

That point was evident to me in the 1990s when I first really got into Townes and when he was still performing and releasing occasional new music. What those of us tuning in then found was a combination of voices: the singer of the earlier recordings, who used a voice that was already ‘late’, already ripe with accumulated experience; and the ‘real’ late voice of a singer approaching fifty but who often sounded much older, a voice limited in some ways but warmer and possessed of a deeper blue. We lived with, and trusted, both those voices.

In thinking about what I felt I was getting from the songs, I wondered whether trying to categorise them would help.

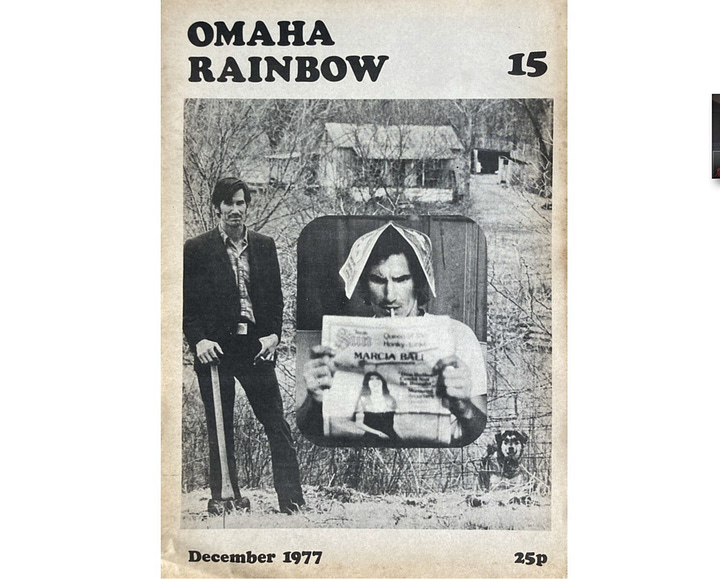

In a 1977 interview printed in Omaha Rainbow, Townes categorised his songs as follows: ‘Some songs are about feelings, some are autobiographical, some are things you want to say, and then there are story songs that are unrelated to you and sort of drift in from elsewhere’.

If that sounds simultaneously vague and specific—we do, at least, get the repertoire boiled down to four types—then it’s a combination that suits Townes’ songs well. Those songs can be similarly vague (or ‘universal’, which may sometimes be the same thing) and yet contain highly specific and memorable images.

In a 1977 feature on Van Zandt, William Hedgepeth wrote:

‘Townes’ lyrics come across like messages from the outside, dealing not with causes but with solitary passions and undefinable desires. Though they're melodic and woven with warm visions, his songs don't really comfort the mind or offer any affirmations of anything—other than the assurance that here is someone else who is every bit as alone at the core as you yourself have always felt but can't ever quite find the words for. Townes is not so much a performer as a “presence,” and his presence clearly has an impact.’

And, earlier in the same piece:

‘His songs are of parting rites, of greetings and goodbyes, of unappeasable aggrievements, love dissolved in despair, of spiritual leave-takings and the precariousness of human joy. But in none of his compositions is there the remotest flavor of self-consciousness or the sensation that he's trying to convince you of anything—or, indeed, that he's concerned about “impressing” you at all.’

Connecting that to my earlier point about conviction, we could identify a voice not trying to impress or convince but doing so nonetheless. Is what’s so convincing the apparent desire not to be? That makes sense for me.

In her essay on ‘Townes Van Zandt, “Dramatic” Form, and Gender’, Ann Norton Holbrook classifies the songs according to how men and women are represented, how romantic partners are addressed and treated, and to what extent Townes as songwriter was maintaining or challenging socialised understandings of gender. It makes for a thought-provoking set of distinctions and reflections, as does Jim Clark’s essay—in the same collection—on ‘macabre and mirth’ as ‘two sides of Townes Van Zandt’.

As I started to think about my own categories for Townes Van Zandt songs, I realised that I would come up with different groupings on different days. What follows are some of my first attempts. Many of these categories overlap: story songs evoke atmospheres, while the creation of a mood requires a certain amount of narrative action or inaction.

I’ve punctuated my thoughts with several video clips from various points in Townes’ career. I resisted the strong temptation to only add links to versions from Live at the Old Quarter, Houston, Texas, the 1977 album that remains the urtext for many Townes fans, myself included.

Mood or Atmosphere Songs

I suspect this may account for a large percentage of the songs because I tend to think of Townes as someone who, while using very specific metaphors, is often quite abstract in terms of overall narrative.

An exemplary early song here would be ‘Kathleen’. The song’s essential moodiness may well have been part of the appeal for Tindersticks, who released a cover of it as the title track of a 1994 EP. I like Tim Sendra’s description of the Tindersticks version in his AllMusic review: ‘the sound of widescreen introspection’. For me, that encapsulates Van Zandt’s songwriting as much as it does the British band’s sound.

I would think of ‘Flyin’ Shoes’ in this category too. I recall the excitement I felt on finding this record in the early 1990s at a car boot sale in the Devon town where I grew up, and how it seemed to deepen and expand Townes’ repertoire for me and the few other Townes fans I knew. Not only were there songs that didn’t appear on other albums available then—the title track being an obvious example—but the production, instrumentation and arrangements all evoked a new atmosphere. I remember sitting in my bedroom with a friend, playing ‘Flyin’ Shoes’ over and over and getting lost in the combination of Gary Scruggs’ haunting harmonica and Townes’ deep lonesome voice. The spaces connected in that listening space have stayed with me over the years: the floor where the two of us sat, awed, and the spaces we imagined as we let the music carry us away from our hometown.

Story songs

All songs tell stories of one kind or another. They don’t have to be based on reporting sequential actions (‘this happened, then this …’) to give a sense of narrative. That said, it’s not uncommon to think of story songs as those which, perhaps drawing on the long history of folk ballads, take listeners through a set of actions and events. These events may lead to a stated moral, or the lesson or outcome of the story may be more ambiguous.

Examples from Townes Van Zandt include some of his earliest compositions, such as ‘Waitin’ Around to Die’ and ‘Tecumseh Valley’, as well as some of his latest, such as ‘Marie’.

In an interview with William Hedgepeth, Townes described his work as ‘poem songs’ and ‘story songs’. He also felt that his focus on these kinds of songs were one of the things that kept him from finding commercial success. Here’s the longer quotation:

‘The kinda songs I play—poem songs ... story songs—are not what you'd call a particularly accepted mode of art these days. Then, too, those people in Nashville consider me a weird recluse who they've heard of but who never comes to land. I'll come into town, like, five minutes and give 'em a tape and disappear. But still, most of those Nashville folks won't do a waltz. Won't do a ballad. Won't do things in a minor key. Nashville's just not geared for minor keys.’

The video below shows extracts from James Szalapski’s documentary Heartworn Highways, including footage added when the film was released on DVD in 2003. Heartworn Highways was originally filmed in 1975-76 but not released theatrically until 1981. These clips show Townes talking to and playing music for ‘the walking blacksmith’, Seymour Washington, who was a neighbour of Townes and his second wife Cindy when they lived in Clarksville, Texas. This footage brings together two Townes story songs: ‘Waitin’ Around to Die’ (which he often described as the first serious song he ever wrote) and his most famous song, ‘Pancho and Lefty’. It also contains a mini sermon from ‘Uncle Seymour’ about the benefits and risks of bourbon whiskey as well as providing a good example of the way Szalapski tells the story of the progressive country scene of the mid-1970s.

(For a great article on Seymour Washington that also provides some details of the darker side of the outlaw country scene in Clarksville, see this Substack post by Michael Corcoran.)

Surreal story songs

As a subcategory, I think of songs like ‘Mr. Mudd and Mr. Gold’ and ‘Two Girls’ as surreal story songs. The former is a tall tale of (at least) two gamblers which is just about possible to follow as a chronological story but operates more obviously, for me, as a dazzling display of wordplay. Townes is gambling with words here, seemingly laying them down recklessly but ultimately coming up with a winning hand.

This is a song that Townes would often explain to audiences and interviewers as one that came to him in a flash. At the end of one performance, he quips, ‘that song took one night to write and about four months to learn’; after another, he says, ‘that song came to me in a flash, all at once. It wasn’t me that was writing it, it was a giant pencil from the sky’.

‘Two Girls’, meanwhile, provides much surreal detail:

Well, the clouds didn't look like cotton They didn't even look like clouds I was underneath the weather My friends looked a crowd The swimmin' hole was full of rum I tried to find out why All I learned was this my friend You got to swim before you fly

And:

Now, cold down on the bayou They say it's in your mind But the moccasins are treading ice And leaving strange designs The Cajuns say the last time That this happend they weren't here Ah, Beaumont's full of penguins And I'm a-playin' it by ear.

The first verse contains lines that Guy Clark describes as ‘far out, lines that he ‘quote[s] all the time’ (this is from an interview in Brian Atkinson’s book I'll Be Here in the Morning: The Songwriting Legacy of Townes Van Zandt). The ‘all I learned was this’ line also has something that we might well expect find in certain story songs: a lesson or moral.

There’s one of those in ‘Mr. Mudd and Mr. Gold’ too: ‘Here’s what this story’s told / You feel like Mudd you’ll end up Gold / You feel like lost you’ll end up found / So amigo lay them raises down’.

How seriously should we take these lessons emanating from such tall tales? There’s a good lyric annotation of ‘Mr. Mudd and Mr. Gold’ at Genius, where the moral is described as follows:

‘It seems Townes is trying to drive home a moral point: We have the choice to become like Mr. Gold or the obedient Queen and gain the favor of Kings. Or we can shun inscription in the power structure, approximating the more difficult life of the outlaw or Mr. Mudd. In the end, our apparent success in worldly terms is not what it seems, and if gained through greed and power lust, is inverted into failure when viewed from a transcendent perspective.

This being the case, putting your bets and raises behind the more universal viewpoint of morality is the smart money for the LONG GAME…’

I have no major quarrel with this interpretation and I’m impressed with the annotation of the verses, which do a fine job of summarising the story that plays out in this song. For me, what I take from the song is the granting of agency to the playing cards rather than the card players—an inspired move by Townes, and one that sits well with my own fascination with the use of objects in songs—and the sonic pattern of the lyrics. Over the many years I’ve listened to it, I find I rarely follow what’s happening in the game, and certainly not with the attention and logic of the Genius contributor. Instead, I hear a series of sound patterns that emerge from the layering of the main characters: the King of Clubs, the Queens of Clubs and Diamonds, the Jack of Diamonds, Mr Gold and the ultimately victorious Mr Mudd.

That said, an impressive reading of ‘Mr. Mudd and Mr. Gold’ by Paul Thomas Zenki makes an additional point which is perhaps nearer the mark in that it questions whether Mudd is victorious after all. Having established that ‘it’s not a song about men playing cards’, but ‘a song about cards playing men’, Zenki discusses the song’s lesson:

‘What is crystal clear right up until the final stanza is that Mudd and Gold are both utterly in the hands of the fates. The cards control the men rather than the other way around, giving them the urge to gamble in the first place and deciding who will win and who will lose …

And yet, after describing all this, the narrator comes to precisely the opposite conclusion than the one which, by all reason, he should reach. It’s the gambler’s fallacy, the notion that a losing streak mean’s you’re “due” and you should keep taking risks no matter how much you’ve lost.’

Existential songs

I think of many Townes song as existential in that, whatever the story they may be relating, it’s often the lines about eternal, universal or neutral truths that stick out to me. ‘To Live Is to Fly’, for example, may be a song about seducing and/or abandoning a lover, but the lines I tend to recall are ones like ‘Days up and down they come / Like rain on a conga drum’ or 'Living’s mostly wasting time’ or ‘We all got holes to fill / And them holes are all that’s real’.

I’m put in mind of ‘No Place to Fall’ here too. It’s staged as a love song, or at least as an appeal to a partner from a man who ‘ain’t much of a lover at all’. But it’s the lines that look outside the personal relationship to reflect on the bigger picture that speak as loudly to me: ‘Skies full of silver and gold / Try to hide the sun / But it can't be done / Least not for long’; ‘Time, she's a fast old train / She's here then she's gone / She won't come again’.

‘Only Him or Me’, one of my favourite Townes songs, is a leaving song that highlights timeless truths like ‘rain falls and rivers flow’.

While none of the neutral observations above may be in-and-of-themselves existentialist, the actions and choices that correlate with them in the songs could be. That said, it’s never too clear whether the protagonists of these songs are asserting an agency in response to the meaningless and futility of existence, or handing themselves over to a fate that would strip them of agency.

The sad and the hopeless

There’s an interview clip used in Be Here to Love Me where Townes is asked why so many of his songs are sad. ‘I have a few that aren’t sad’, he responds, ‘they’re hopeless … And the rest aren’t sad, they’re just the way it goes. You don’t think life’s sad? No? But, from recognising the sadness, you can put it aside and recognise the happy side of life. Blues is happy music.’

That’s an observation that’s often been made about the blues and it bears repeating. Kevin Young puts it well in the introduction to his edited collection of blues poems:

‘With the blues, the form fights the feeling. Survival and loss, sin and regret, boats and heartbreak, leaving and loving, a pigfoot and a bottle of beer—the blues are a series of reversals, of finding love and losing it, of wanting to see yourself dead in the depths of despair, and then soon as the train comes down the track, yanking your fool head back.’

This might be the place to note the number of testimonials that can be found online about the therapeutic aspect of Townes Van Zandt’s music. From the evidence, it seems these songs have helped a lot of people over the years, got them to yank their fool heads back.

I think some of the things I was drawn to all those years ago—alongside the self-evident poeticism, the melodic beauty, that voice and that guitar—were the self-deprecation in the delivery of the songs, the willingness to present a darker perspective, and the commitment to not always having to bear up.

The admission of defeat and despair and the recognition of the truth in melancholy that came through Townes’ songs was refreshing, just like the blues that he drew so deeply from. This is something I would later come to appreciate in another genre, Portuguese fado: there is this situation, it’s desperate, but it’s also how life is, and not only is it okay to reflect on this and embrace it, but you can also make beautiful things from it. Like the best fado singers, the best blues and country artists, Townes created some of the most beautiful things that had ever been made from the acceptance of despair.

It’s something I realised I needed when I was young and which I still feel the need for from time to time, whenever I notice the imperative in our culture to always bear up, to not put yourself down even in a tongue-in-cheek manner, to be always on your A game.

Highs, lows and in-betweens, or, craft vs. fatalism

As someone who had lived with the songs of Townes Van Zandt for at least three decades before I tried thinking about them academically, I enjoyed, but also felt a bit strange about, the deep scholarly dives to be found in the University of Texas Press collection For the Sake of the Song.

I enjoyed them because they make a pleasant change from all the publications that focus on the wild tales that surround Townes. Instead, they make the songs the central focus, supporting the suggestion made by Townes’ oldest son, JT, that the songs are where we should be looking rather than ‘any stories that may or may not be true’ about his father.

At the same time, I found some of the academic readings a bit too literal, or rather assuming an authorial intent that might be hard to support. I don’t want to make too much of this, especially since most of my own publications embrace the serious attention that I believe popular music deserves. For that and other reasons, I won’t go to the other end of the spectrum and say that the songs should be left to speak for themselves (even if part of me sometimes wonders if that might be true).

I think my in-between spot might be something to do with Townes’s poetic imagery and the sonic element of that, what comes through his singing and guitar playing. I’d already been thinking about this and collecting some of my favourites images and sounds as I made the notes that fed into this piece. Then I read the following in Jim Clark’s essay on the macabre and mirthful aspect of Townes’ songs: ‘[John] Kruth shares this quote from Van Zandt: “Robert Frost said, ‘Worry about the phonetics, and the meaning will take care of itself.’ I hope he’s right.”’

Clark adds in a footnote, ‘I have been unable to locate this exact quotation. It seems likely that Van Zandt had in mind Frost’s similar statement in a letter to Louis Untermeyer in 1915: “Take care of the sound and the sense will take care of itself”.’

Intrigued by this citation nest, I looked up the Frost reference and, sure enough, there it was. One reason I was intrigued was that Frost is here inverting a line from Lewis Carroll, a line I also used as the opening of my book The Sound of Nonsense. In Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland, the Duchess offers Alice one of her many ‘morals’: ‘Watch the sense and the sounds will take care of themselves’. It’s a play on the saying ‘watch the pence and the pounds will take care of themselves’.

As I wrote in my book, ‘The Duchess, like her creator Lewis Carroll, seems to put more emphasis on the sound of words than their sense’. Just as Carroll is playing with the sound of the language to make sense of the rearranged saying, Frost confirms what is already implied: sense can follow sound.

If that is what Townes was getting at, then it’s a good cue to flag a few more aspects of his songwriting. One is his interest in Frost. A second is the way his songs may make sense through the sounds of the words as much as their semantic meaning. A third is his suggestion that certain aspects of songwriting might take care of themselves, a nod to the kind of fatalism that has emerged as a dominant strand in everything I’m writing about here.

In one of the interviews collected in Paul Zollo’s Songwriters on Songwriting (the later, longer edition), Townes says, ‘Some people don’t know what to think when you tell them your two biggest influences are Lightnin’ Hopkins and Robert Frost’. The discussion that comes out of this looks like it could set up familiar distinctions between ‘high’ and ‘low’ culture, but Townes is quick to realise the potential problems there. ‘It’s murky territory’, he says, ‘because you can’t say that Hank Williams isn’t thoroughly poetical. And Blind Willie McTell, too. And Lightnin’ Hopkins, too.’

This interview is quoted by Townes’ biographer Robert Hardy, who, in his contribution to Pickers & Poets: The Ruthlessly Poetic Singer-Songwriters of Texas (reprinted in For the Sake of the Song), nevertheless pursues the implications of the ‘high, low and in-between’ aspects of Townes’ songwriting as a space between ‘serious’ American poetry and the vernacular tradition.

As to where the songs came from, I’ve already mentioned the case of ‘Mr. Mudd and Mr. Gold’, which Townes would regularly cite as an example of a song that came almost unbidden. But he also recognised that this was only one type of songwriting experience, telling Paul Zollo ‘I have songs of every degree, from pure craftsmanship to inspiration’.

‘Of all my songs’, he continues, ‘“Mr. Gold and Mr. Mudd” [sic] was closest to just coming out of the blue. It was back when I was doing a lot of drinking and gambling’. He proceeds to tell the story of how he went into the kitchen with his guitar and the song came to him in a three-and-a-half-hour period. ‘It felt like my arm was going to drop off’.

Asked by Zollo if there’s a part of him that’s always writing songs, Townes replies, ‘The subconscious must be writing songs all the time. I’ve heard a lot of songwriters express the same feeling, that the song came from elsewhere. It came through me.’

‘On songs like [‘Mr. Mudd and Mr. Gold’], it was a definite feeling that anyone could have been sitting in that chair at that time in South Carolina with a pencil and paper and had the ability, that kind of mind that was in tune with that, with songwriting, it felt like anybody could have written that song … That song was there. I’ve had that feeling with other songs, certain Guy Clarke [sic] songs or Bob Dylan songs, John Prine songs, I feel, “Man, why didn’t I write that! That song was out there and I didn’t get it.” You get that feeling the first time you hear it: “Man, that song was in me, too”.’

I’ve written quite a bit in previous posts about Christopher Bollas’s writing on ‘the unthought known’, potentialities that we’re partially aware of but need some transformative experience to understand (which Bollas suggests often comes via art), like discovering a truth that has been lying in wait for us. The quotation above (which comes from the Zollo interviews) puts me in mind of this.

But I also feel that fatalism is at work here, for example when Townes says.

‘The way I feel about it is, my part of this whole scheme is just to hit whatever particular note feels right in that particular moment. Try to do what I can with my voice, and after that happens, well, the rest of it is just beyond me. Whatever happens … happens!’

The contrast to this is the ‘pure craftmanship’ he mentions. In another interview, from 1993, he talked about the influence that his study of poetry as a senior in school had on his songwriting:

‘I wrote some sonnets. Just … the rhyme scheme was so weird, I wanted to see if I could do it and make any sense. These days I have a couple of songs like that where I came upon a strange rhyme scheme and just almost academically wanted to see if I can follow it through without throwing away any lines and still have it make sense.’

Going back to the point made earlier about the sound leading the sense, I assume that, for some of the songs, it was about finding the right-sounding word as much as anything. Townes’ early fascination with rhyme schemes would seem to support this.

‘She Came and She Touched Me’ is a good example. It’s the song that Townes is talking about when he references Frost’s point about phonetics leading semantics, as cited by John Kruth and Jim Clark. The song luxuriates in alliteration and intricate rhyme:

Where the wind careens madly through wide windows paneless Fragrances mingle in a room full of shade The peons pick partners and waltz across the ceilings But the violins whisper that I've been betrayed Tryin' not to look ashamed

And:

Well, illusions projected on walls made of tiffany Mad minuets to a sad satin song Harlequin mandolins harmonize helplessly Hoping that endlessly won't last for long Praying that their God ain't dying

(It’s interesting to compare this to ‘Helplessly Hoping’ by Crosby, Stills and Nash, as Jim Clark does in For the Sake of the Song. It’s not just the ‘helplessly hoping’ line; Stills’ whole song is awash in similar alliteration. The jury’s out on which came first but Clark cites convincing testimony from Mickey White, Townes’ friend and fellow musician, to believe that Stills was second.)

If ‘She Came and She Touched Me’ represents the sound of intricacy in Townes’ work (evident in other early songs such as ‘Quicksilver Daydreams of Maria’), there is also a sound of concision that comes through in both writing and singing voice. There are examples in the early work—’Waitin’ Around to Die’ or ‘Tecumseh Valley’—but the example I often turn to is ‘Still Lookin’ for You’ from the 1987 album At My Window.

There’s that killer opening couplet: ‘There ain’t much that I ain’t tried / Fast livin’, slow suicide’. But it’s also the high lonesome draw(l)ing out of the ‘lookin’ low/high/far/wide’ lines that mark this as a perfect distillation of honky tonk haiku.

Lineage and legacy

This has been long, and so I’ll bring it in to land with two more clips. The first is ‘Rex’s Blues’, the version from Live at the Old Quarter. It’s another reflection on highs and lows, with verses built from the kind of contrasts that populate so many Townes Van Zandt songs and stories. The opening verse sets the scene:

Ride the blue wind, high and free She'll lead you down through misery Leave you low come time to go Alone and low as low can be

There’s the illusion of freedom, of flying free, but the wind is fate and, as we’ve learned, fate flies in the face of freedom. Another verse has the singer ‘chained across the face of time’, but—that contrast again—‘bound to leave the dark behind’.

The final clip is a return of sorts to biography, an approach I said at the outset of this piece that I would mostly avoid. I’ve stayed true to that (at least with regard to Townes’ biography: there’s some autobiography), but I find this clip so touching that it seems a good way to sign off this rambling, but still surface-skipping, account of Townes Van Zandt, his music and his legacy.

I’ve alluded above to the high, low and the in-between, drawing the term from a Townes song that I haven’t otherwise discussed, the title track of a 1971 album. ‘High, Low and In Between’ is Townes-abstract for the most part, but also contains several references to familial relations and lineages. ‘What can you leave behind when you're flying lightning fast and all alone?’ he asks. ‘Only a trace, my friend’.

There’s another point about fatalism here, one that comes through things that Townes’ sons JT and Will have said in interviews about their father and his legacy. I cited JT earlier on the need to focus on the songs rather than the wild tales. Will Van Zandt has also spoken about his use of his father’s music as a form of reconciliation with the past.

The clip below is about the role of fishing in JT’s life and how he has found a place in the high, low and in between. It’s a beautiful piece of filmmaking and marks the place where I want to stop for now.

It's a brilliant piece of writing, Richard. I enjoyed it very much. Perhaps - just perhaps - I was the friend (mentioned above) in your room listening to Flyin' Shoes over and over. I remember wonderful afternoons sitting around in your cluttered (books and records) room on St. Leonard's Road listening to a wealth of music (with an eye on the clock waiting for the pubs to reopen!). Of course, it was you who introduced me to Townes (and Guy too), I hope I didn't scratch your copy of Live at the Old Quarter too badly - played repeatedly on my rickety old stereo. Of live TVZ albums, I listen a lot to 'Rain on a Conga Drum - Live in Berlin' - you taped it for me when it was first released (circa 92?) when I was at Uni. (The tapes you sent me were a lifeline back then.) It has become one of my favourite albums . . . ever. Townes sounds happy, content, (one reason I think why I love the album so) and he plays a storming set. He starts off with Mudd & Gold and plays it (almost) flawlessly so you know it's gonna be a good night. It is incredible the depth of his songwriting when you glance at the eighteen tracks on the record - the second side alone: No Place to Fall, To Live is to Fly, Lungs, Nothin', Tecumseh - one after the other. Not many songwriters can boast of such riches. And I haven't even mentioned a couple other songs on side 2 that measure up to the best of them or the treasures to be found on the first side, If I Needed You, Dollar Bill Blues . . . and a certain Pancho & Lefty. Wow-wee! (I am no longer much of a fan of Steve Earle but I would also get on Dylan's coffee table and claim, at least, that Townes was equal in stature to Mr. D.)

Anyway, Richard, it was nice coming across this piece. Great stuff. I want to also thank you, in closing, of the comp you made for me many, many years ago of The Dark & Cold Dog Soup (by Guy) housed in its own homemade sleeve, created by you. I still have it. A lovely thing.

All the best,

Martin

P.S. I found out recently that Townes wrote both 'Lungs' and 'Nothin'' after reading and being inspired by Nikos Kazantzakis. And there I was thinking my respect for TVZ could not climb any higher!

Really enjoyed this. I was also confused for a bit with the part about the Clarksville music scene. I had a hard time picturing the town of Clarksville, Texas having any kind of scene. Once I realized it was a neighborhood in Austin, it made much more sense.

If you’ve never seen it, there’s a great video of Lyle Lovett doing White Freight Liner Blues on Letterman.