I’m listening to Cat Power’s wonderful new album Cat Power Sings Dylan: The 1966 Royal Albert Hall Concert and I’m thinking about Bob Dylan as an object.

I’m also thinking about objects in Dylan songs and how Dylan creates new objects from other people’s objects, how he twists word-objects into new forms. I’m thinking about how Chan Marshall (Cat Power) has reminded us of the mashed-up palimpsest object that is the Royal-Albert-Hall-Manchester-Free-Trade-Hall-Dylan-live-in-1966 event-as-thing.

I’m smiling at the way the short version of Marshall’s title – Cat Power Sings Dylan – hides the true ambition of the record, as though it were yet another of those collections of Dylan covers. It is that but it’s more.

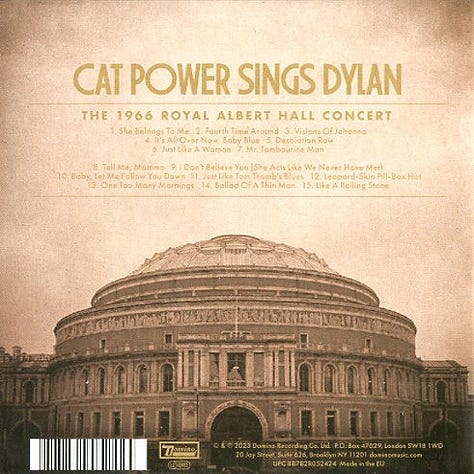

We’re used to cover versions of songs and occasional recreations of whole albums (think Ryan Adams’ take on Taylor Swift’s 1989 or, more obscurely, Occasionally David’s reproduction of Love’s Forever Changes). Covering studio recordings with new studio recordings is one thing; doing a cover version of a live event is something else. As I listen to Cat Power Sings Dylan and, later, as I read what other people (including its creator) have had to say about it, I start to realise that it is both a document of a live event AND a cover version of a famous album and that those two things are equally interesting.

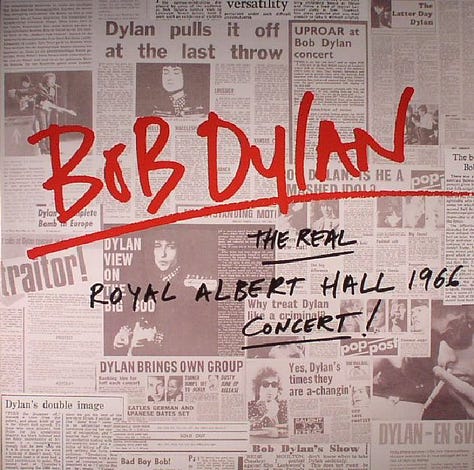

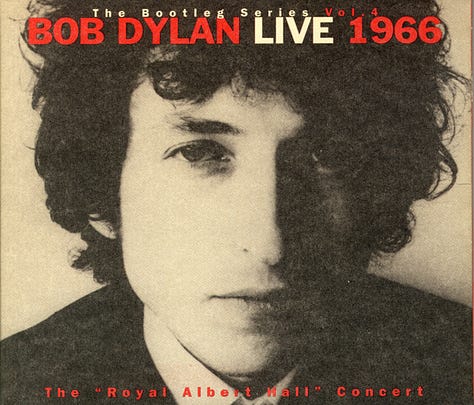

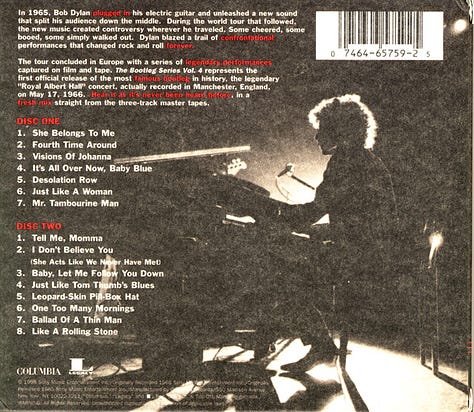

That gets me thinking about objects and events, and about songs as objects and events. Covering a one-off live event means being at a particular place, doing particular things in a particular order, recreating a long-forgotten atmosphere. Covering an album—in this case the infamous bootleg album that claimed (wrongly) to be a recording of one of Dylan’s Royal Albert Hall concerts from 1966—means taking what has become familiar and homely through repetition and bringing it all back ‘home’ in a manner that may ultimately be unhomely.

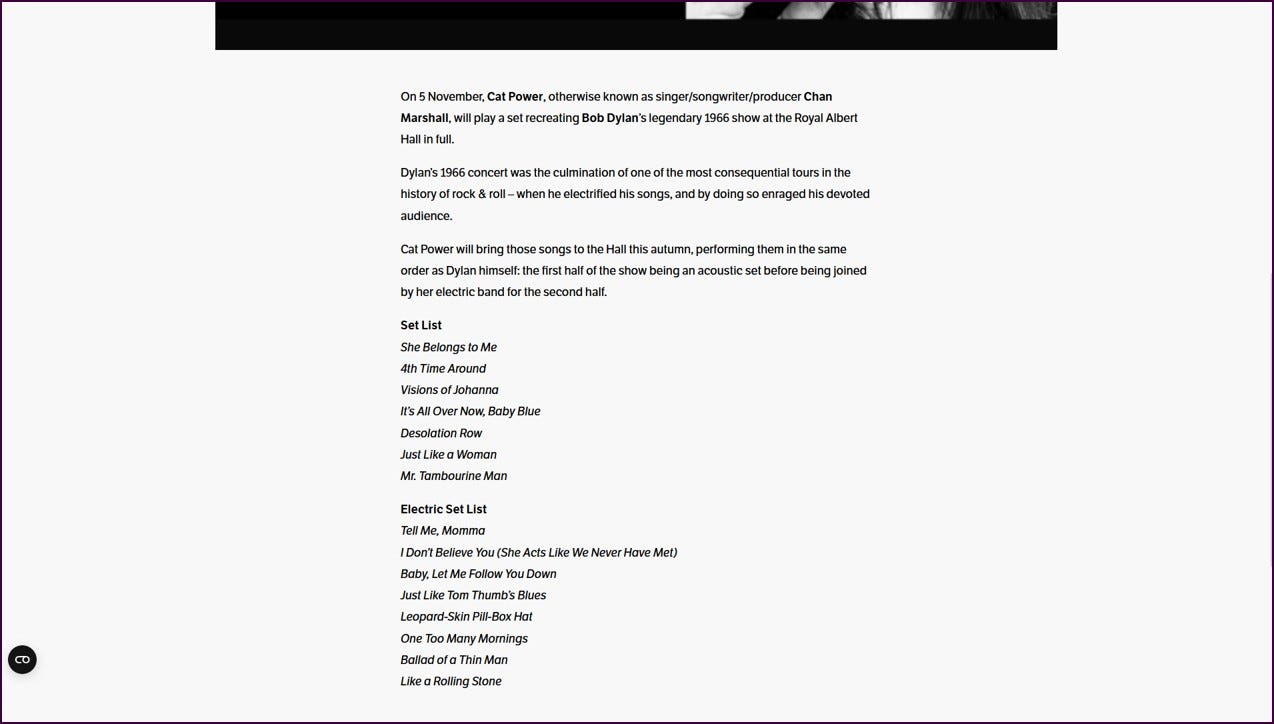

There’s some blurring of details around exactly which event Marshall was recreating when she performed the concert that features on the new album. Offered the chance to play London’s Albert Hall on 5 November 2022 following the positive UK reception of her album Covers earlier that year, she insisted on doing a Dylan-only set and recreating the iconic 1966 setlist that became immortalised in the bootleg. The Albert Hall promoters were clearly keen to advertise Marshall’s 2022 show as a recreation of one of Dylan’s London concerts.

Others felt the need to issue correctives. In a Guardian feature on Cat Power published the day before her London show, Laura Barton wrote:

The Royal Albert Hall show will recreate the erroneously titled bootleg recording that was actually made at Manchester Free Trade Hall in spring 1966, surfacing several years after the event and officially released in 1998. The first half is an acoustic set, and the second played electric. It marked the pivotal moment in Dylan’s career when he turned away from his folk roots, incurring the wrath of some of his audience.

That corrective has followed through into reviews of Cat Power Sings Dylan. Andy Cush’s Pitchfork review argues that Marshall’s naming of London in the album’s subtitle is a way of showcasing ‘another kindred aspect between [Dylan’s] trickster spirit and her own: the understanding that myth can be just as powerful—in its way, just as truthful—as fact’.

Is Dylan’s ‘trickery’, then, the object that is being recreated by Cat Power? Perhaps, but all of this only works due to an insistence that there must be a pivotal moment, a single event, to make the myth effective.

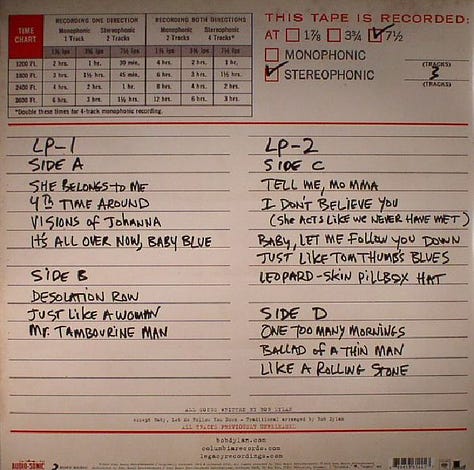

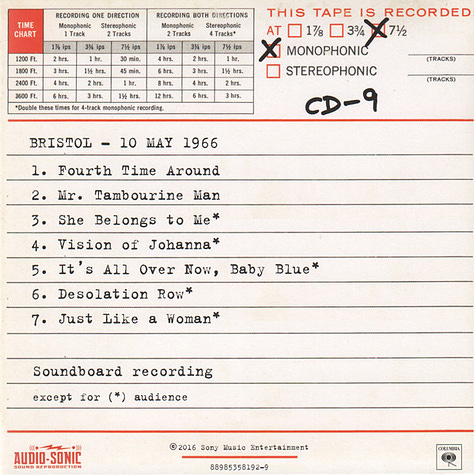

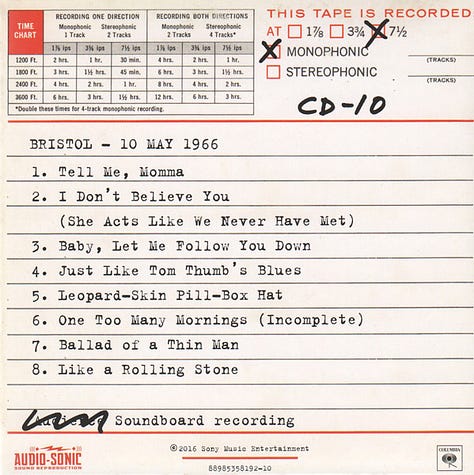

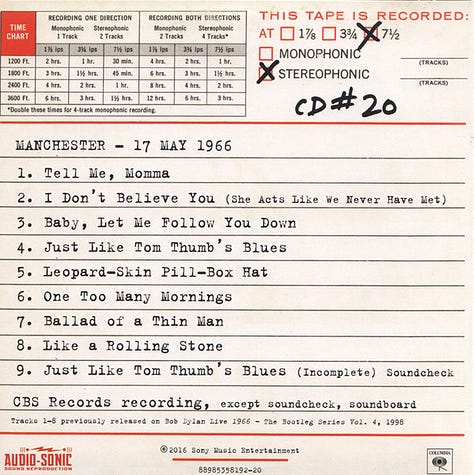

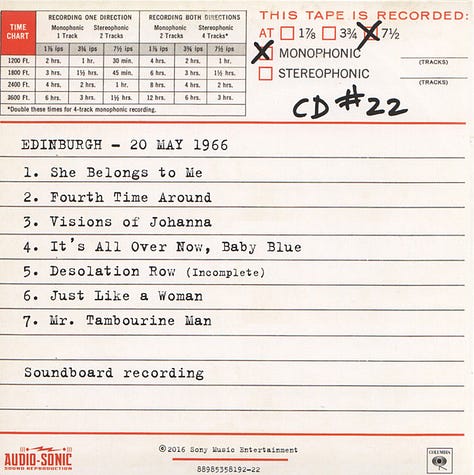

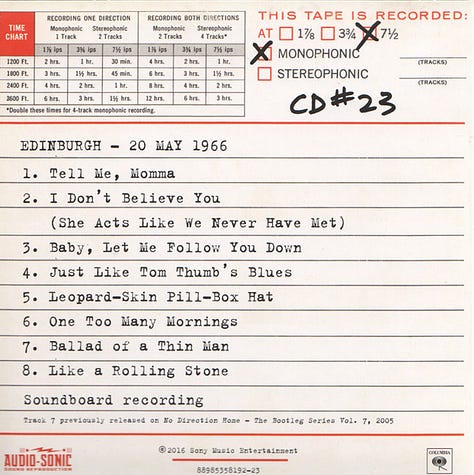

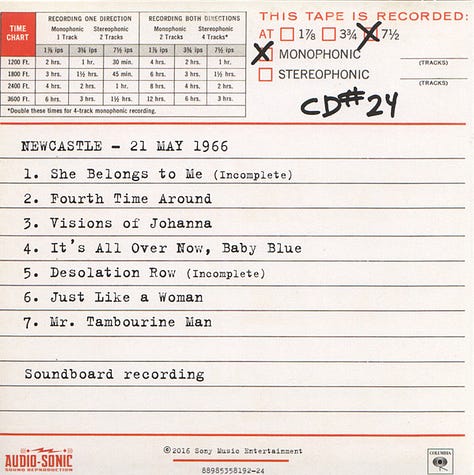

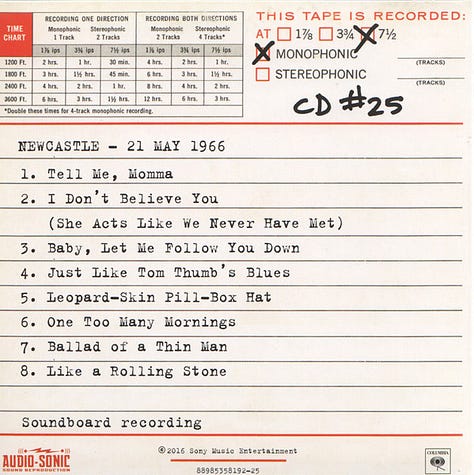

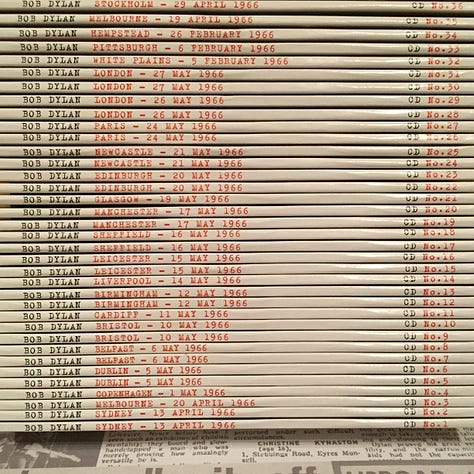

It’s worth recalling that Dylan performed the same set list on all of his shows in the UK and in many of the shows elsewhere in 1966. This is brought home in the 36-CD box set The 1966 Live Recordings (released in 2016) as the repetitive nature of the shows reveals them as objects in their own right, or at least multiple collections of multiple remarkably similar objects. The differences in each set are just as interesting, of course, but they don’t stop those fifteen songs that appear in nearly all the 1966 setlists being recognisable versions of the same objects. As Jesse Jarnow put it in a review of the box set, ‘Listening to oblique narrative epics like “Visions of Johanna” and dense truth attacks like “Leopard-Skin Pill-Box Hat” over and over, each becomes like a sculpture viewed from different angles, each liable to reveal something new about the lyrics or melody or interplay between musicians.’

History, especially if it is to become myth, loves singularity over repetition. Perhaps it’s unsurprising that—to make up for the mislabelling of the ‘Royal Albert Hall’ object and to clear up where the famous ‘Judas!’ heckle actually happened—the consistency of Dylan’s live shows in 1966 has been forgotten. But what enabled that initial mislabelling was precisely the use of the same setlist in Dublin, Belfast, Bristol, Cardiff, Birmingham, Liverpool, Leicester, Sheffield, Manchester, Glasgow, Edinburgh, Newcastle and London. There may not have been a shout of ‘Judas’ at every show but it would be a mistake (however well it suits the myth) to reduce the concerts Dylan was playing at this time to this one moment. As Clinton Heylin put it in his liner notes to The 1966 Live Recordings, ‘Manchester was no one-off’.

And, brilliant and invigorating as it evidently was in 2022 and as it remains in its recorded version, Chan Marshall’s recreation of ‘the’ Dylan concert is no one-off either. She is in the process of taking the show to multiple cities in the US and elsewhere in what has become a promotion of an album that was released to document a supposedly singular live event.

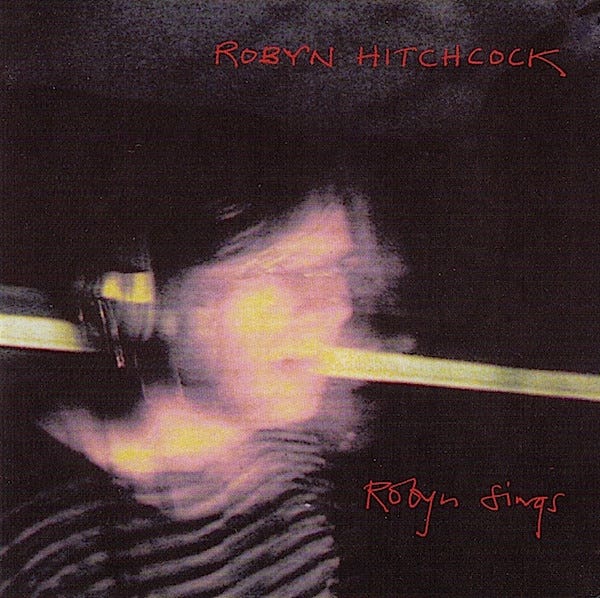

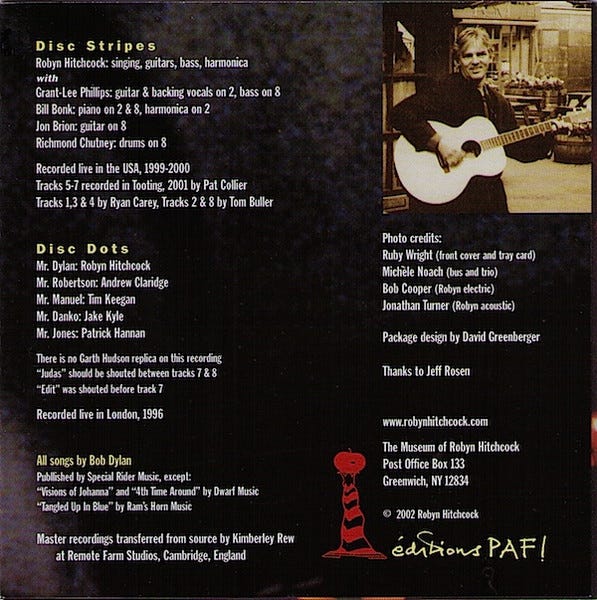

Nor is Marshall’s endeavour in concert archaeology unprecedented. In 1996, to celebrate the thirtieth anniversary of Dylan’s ‘Royal Albert Hall’ concert, the singer-songwriter Robyn Hitchcock staged a recreation at London’s Borderline. The show can be heard more or less as it went down via the Internet Archive. It was also released in more selective form as a 1997 promo CD and as the second disc of Hitchcock’s Robyn Sings double CD from 2002.

Hitchcock’s liner notes to Robyn Sings are well worth reading. His recollection of how the discovery of Dylan affected him as a teenager is a great example not only of the epiphanic moment and the recognition of ‘the unthought known’, but also of the viral, hyperobject-like aspect of songs:

When I was just thirteen, sweeping the floor one evening in the private monastery where l was privileged to be incarcerated, “Desolation Row” came on the mono record player that serviced us inmates. Stereo was a little way off yet. I thought Bob Dylan was singing “Destination Roll,” but I was magnetized anyway. Never in my thirteen years had I been exposed to such a powerful force ... it somehow altered my molecular structure … like a virus looking for a willing organism to roost in.

Hitchcock goes on to note ‘the transformed creature that I became after hearing "Desolation Row"’, a line that reminds me of what the psychoanalyst Christopher Bollas says about encounters with art as transformative experiences. ‘I didn’t write any of these songs’, Hitchcock claimed at the start of his Borderline set, ‘but they wrote me’.

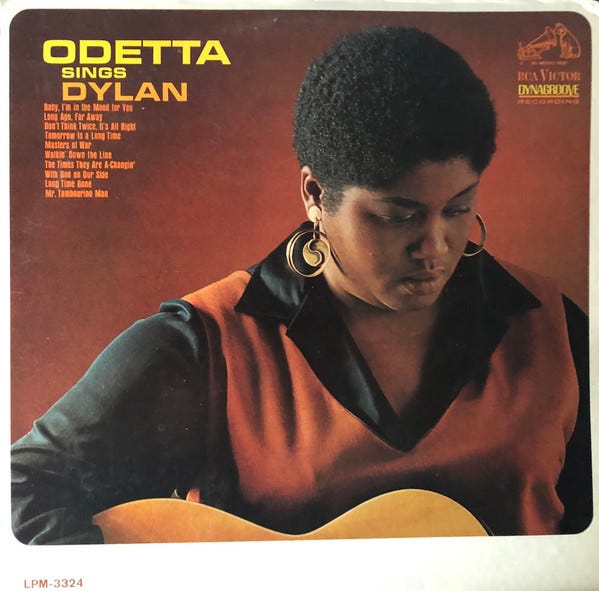

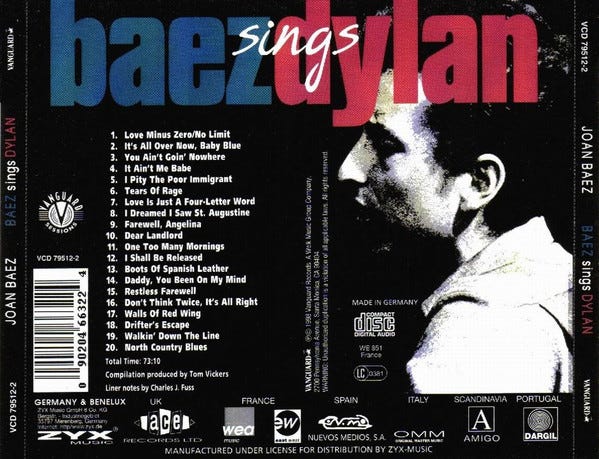

Both Marshall and Hitchcock have mentioned that they were mainly wanting to pay homage to Dylan with their concert-cover records and that they are not going out of their way to reinterpret his songs. Perhaps following a practice maintained by veteran Dylan-coverer Joan Baez over the years, each mixes their own voice with occasional Dylan imitations, aided by a temptation offered up by Dylan’s distinct way of phrasing particular words, syllables and lines. This was a feature noted by Odetta in the liner notes to Odetta Sings Dylan, a 1965 album that must rank as one of the pioneering works in album-length Dylan-versioning:

Because of the strength of Bob Dylan’s songs, especially in his presentation of them, it is sometimes quite difficult to resist imitating him. But something did not allow me to become a reflection. I believe it is known as the “ego.” Thus, when Mr. Dylan’s songs and I got to working together, I made some lovely discoveries; one being Dylan’s own turn with the melody, whether his own or adapted. Another discovery—the young “old” man; i.e. the wonder of how young Dylan can reduce to words such powerfully emotional content which comes out of wisdom usually attributed to a long span in time and living experience.

Odetta’s way of bringing out that experience, of relating Dylan’s late voice to her listeners, results in some remarkable renditions, the most outstanding of which, in my opinion, is her ‘Mr Tambourine Man’. It’s a challenging listen, drawing out the song to nearly eleven minutes and losing any of the dancing chirpiness that marks Dylan’s original recording (a feature maintained even in his extended 1966 versions via some jaunty strumming on the guitar). It has virtually nothing to do with the Byrds’ famous two-and-a-half-minute breeze through the song, even if that group did enact an era-defining reinvention of its own.

If the song-objects by Odetta and the Byrds are so radically different as to put in question whether they even have a common source, Cat Power’s ‘Mr Tambourine Man’ is clearly modelled on Dylan’s more relaxed 1966 versions. Though known for drastic reinvention in her previous covers, here she mirrors Dylan, albeit with some subtly pleasing distortions. Where Marshall is perhaps most faithful to Dylan’s word-objects is the way that she plays around with them, exposing their malleability.

As noted Dylan analyst Michael Gray has often pointed out, how Dylan voices his lyrics is as much a work of authorship as the choice of words. The following is from Gray’s commentary on the middle eight or bridge in ‘Just Like a Woman’, a construction that, for Gray, elevates the song from banal sentimentality:

Singing those words, those unit-construct lines, Dylan moulds and holds out to us a hand-made object with much tactile appeal. You need the recording for the indescribably plaintive resonance the voice yields up on those simple little words like “rainin’”, “first”, “came” and even “ain’t”; and you need the recording above all because that long middle line demands Dylan’s own pronunciation, by which “curse hurts but what’s worse” becomes five equal fur-mouthed jerks and “what’s” rhymes gleefully with “hurts”. You have to hear Dylan doing it.

Right now, I’m hearing Cat Power doing it. To my ears, she sounds at her least Dylanesque when performing this section of the song, then at her most in the line that immediately follows it, the one that hinges from the bridge back to the verse: ‘I just don’t fit’. The emphasis she places on ‘fit’ would fit Dylan perfectly.

Vocal imitation of Dylan—the kind that Baez perfected and that Marshall gets just right at just the right moments, just like a mimic who knows when to bend and when to break the song open—is a way of objectifying a subjective experience. Like when Robyn Hitchcock writes of his versions, ‘I'm not interpreting these songs, l’m just singing them—as only someone who's been saturated in them can. They all came out of Bob Dylan, but they've spent a lot of time in me, too’.

‘I’m an object to you’, Dylan complained in an interview-cum-provocation with Laurie Henshaw in 1965. Lee Marshall, in his excellent book Bob Dylan: The Never Ending Star, quotes the exchange as an example of the kind of ‘anti-interview’ Dylan would increasingly engage in as his celebrity status exploded. That status has only proliferated over the years, offering generations of followers different perspectives on Dylan while leaving him radically unknowable. Just like an object, in other words.

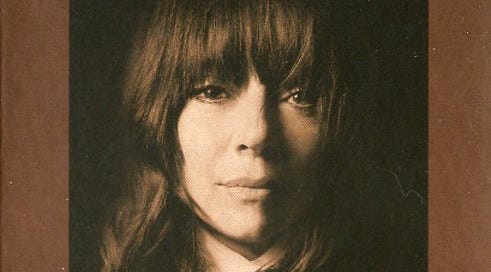

It’s Dylan-as-object that I keep circling back to as I listen to Cat Power, noting how she puts on his voice, how she dons his image on the album cover, even how the pseudonym ‘Cat Power’ echoes the pseudonym ‘Bob Dylan’ in its letter count. When, in her tour-de-force take on ‘Desolation Row’, she sings the lines about rearranging people’s faces and giving them all another name, I’m reminded of the traceable-yet-elusive trajectories of so many songs, singers and other objects.