Words from the New World Part 2: Patti Smith and the Weight of Horses

Can those who write about Patti Smith manage to see beyond her most famous album?

This is the second of three posts about Patti Smith’s later work. Part 1, which provides an overview of the 2012 album Banga, is here. Part 3, which offers an alternative reading of the same album, will be published next week.

Retrospection

Having offered, in my last post, an initial account of Patti Smith’s Banga that emphasised adventure, I now turn to retrospection, memory and the past in relation to Smith’s life and work more broadly. To do that, I need to discuss the moment in the 1970s that cemented her reputation: the release of Horses. While I’m not discussing that album at length here, I have to note its inescapable presence. Nearly everything Smith has done in her post-Horses career has seemed to refer to that seminal album.

The retrospection I’m thinking about has occurred partly due to, and partly despite, Smith herself, who continues to emphasise her other artistic practice and her ambitions for future projects. But mention of her pioneering debut album is never far from other commentators’ accounts when describing current work.

Another reason for mentioning Horses is that I wish to emphasise how, for all its ambition, Smith’s debut album was a work grounded in its creator’s own fascination with paying tribute to the past. It’s in the Janus-faced combination of future and past, of the merging of adventure and memory, that we find the most continuous thread of Smith’s art.

As I mentioned in last week’s Banga post, the first decade of the 2000s was a fruitful period for Smith in terms of artistic production across a range of media. It was also a time for others to re-evaluate and canonise her work. Several biographies appeared, as well as book-length critical analyses that presented variations on the theme of the Patti Smith story, especially the period surrounding her debut album. Published shortly before the millennium, Victor Bockris’s biography of the artist took the story up to 1998 in an account that also served as a memoir of Bockris himself. A biographer of Andy Warhol, William Burroughs and Lou Reed, amongst others, Bockris had been a participant in the New York poetry and punk scenes in which Smith had first found fame.

Bockris’s biography joined an earlier one by Nick Johnstone, which was subsequently updated. Dave Thompson’s 2010 biography brought the story up to the Dream of Life film and Just Kids. Joe Tarr’s 2008 book The Words and Music of Patti Smith offered a more academic account of Smith’s life and work and contained some of the most detailed and convincing interpretations of Smith’s art to be published. Two books ostensibly about Horses—Philip Shaw’s 33 1/3 entry on the album and Mark Paytress’s Patti Smith’s Horses and the Remaking of Rock ’n’ Roll—contained extensive biographical material covering the period before and, in one case, after Smith’s landmark album.

All these texts, along with other canonising processes, have contributed to the re-creation of Horses as an event. To a certain extent, this had always been the case, but an additional element was the retroactive reinforcement of Horses as an unsurpassable moment that accompanied accounts of Smith’s entire career. Even Just Kids, while mainly about Smith’s relationship with Robert Mapplethorpe, reads partly as a teleological account of the creation of her first album. Paytress, despite claiming not to be writing a biography of Smith, spends half of his book setting up a context for the arrival of Horses that requires a significant amount of biographical and other cultural and historical information. Smith’s early life one becomes a narrative that led inevitably to her debut album. Shaw, despite his book appearing in a series devoted to individual albums, spends more time on context than text, a process that only intensifies the ‘eventness’, or the weight, of the album. Tarr, while covering a broad range of Smith’s work, also posits Horses as an event. The weight of Horses is such that it has become a culmination of what led to it and a point of continual reference after its appearance, as Paytress makes clear when describing Smith’s 2005 Meltdown performance as ‘a celebration of an alternative tradition where all roads led invariably to Horses, the inspirations that lay behind it and the imprint it has left’.

The weight that Horses must bear means that, for some critics, little that Smith has done since the 1970s can really compare. Going against those critics who praised Banga on its release in 2012, Jim Farber found the album compared poorly to its 1975 predecessor:

While “Horses” presented a new-fangled wild child, full of sex, attitude and danger, “Banga” suggests a self-styled Mother of Us All, out to nurture, savor and memorialize anything she can get her hands on. Nearly every song on the CD salutes or eulogizes someone who’s either imperiled, lost or, in Smith’s mind, worthy of canonization […] It’s a slog of overawed images, bloated by angels, gods, devils, oracles, baptisms, salvations, laurels, saints, icons, and sisters of mercy.

What Farber seems to miss in this account, however, is the extent to which Horses was itself a memorialising event and Smith an elegist from the start of her career. As Tarr observes, ‘Much of Smith’s work has been a tribute to artists and musicians who have inspired her, building on their ideas and work, interpreting their classics, mourning their loss, imagining their epiphanies and dark moments’. This is as true of Horses as of subsequent work. The album opens with death and resurrection, its infamous first line—‘Jesus died for somebody’s sins but not mine’—acting as a prelude to a piece of rock and roll archaeology as Smith and her band tap the 1960s classic ‘Gloria’ for unexploited treasure. As Mark Paytress comments, if Smith’s religious references work as a method for ‘putting her own martyrs, those who’d died in the name of rock’n’roll, to rest’, then the act of musical revival serves as

a thrilling new-for-old moment, up there with Presley’s baton-passing routine with the old hillbilly boys, and the Stones’ trade-off with the bluesmen of Chicago’s South Side. And, like both Elvis and Jagger, Smith possessed a voice that lifted the material out of the grave and into the future now.

Throughout Horses, Smith displays what I call early or expected lateness, and this is clear in several ways. First, she entered the public sphere at the time of rock’s lateness, a period when, according to both contemporary and subsequent accounts, rock and pop had entered a time of maturity following the ambitious experiments of the 1960s (Tarr and Paytress, not untypically for writers looking back on this period, make much of the sloth of rock in the early to mid-1970s).

Second, Smith was (and remains) a ‘subject’ to rock in that she started as a fan of 1960s rock stars, came to understand her own artistic subjectivity in ways made possible by rock music and was committed to an open display of critical fidelity to the possibilities of rock.

Third, and closely related to this issue of critical fidelity, Smith began her rock career via various acts of mourning for rock’s ‘martyrs’: Brian Jones, Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin, Jim Morrison.

Fourth, Smith herself was older than was typical for new and emerging pop/rock stars and carried with her a sense of urgency, which she made vocal in interviews of the time.

Smith shared some of these aspects with Bruce Springsteen, her contemporary and occasional collaborator. While Springsteen was born later than Smith and therefore entered the public sphere younger, he still embodied—in musical style, lyrical preoccupation and performative zeal—a sense of critical fidelity to rock that could only have come about through a second or third generation subjectivity. Smith and Springsteen, both rock archaeologists, were seen as heralds of rock’s future directions. Both embraced a sense of adventure, voiced in terms of escape and giving oneself up to the body, in infinitely unfolding freefall poem-songs married to electric guitars and propelled by rock machinery. Paul Williams captured this twofold nature when he wrote of Smith as being

the herald for a new moment in rock and roll, third generation. She quotes Chuck Berry by quoting the Rolling Stones; lights candles to Hendrix and Jim Morrison; writes crazed brilliant anarchic poetry using “land of 1000 dances” as a lyrical and spiritual reference point.

I’ve used the terms ‘archaeology’ and ‘treasure’ deliberately because they might help us think of looking back as a kind of adventure, a quest for something buried, nearly forgotten, perhaps not yet known, but remembered or imagined by the archaeologist. Smith brings past and future together in her fieldwork, laying out a plot, demarcating reference points, positing possibilities based on existing knowledge and guesswork.

We also find those processes in improvisation. Tarr relates that Smith and her band would use the term ‘fieldwork’ to describe the simple rock templates they used as the basis for extemporisation.

Archaeology is also about time travel, darting between classical times, the sixteenth century, the nineteenth or the twenty-first. I like what the media theorist Siegfried Zielinksi does with the term ‘anarcheology’, which he borrows from Michel Foucault via Rudi Visker. Zielinksi defines the term as a search for certain sources that lead to unexpected paths:

A history that entails envisioning, listening, and the art of combining by using technical devices, which privileges a sense of their multifarious possibilities over their realities in the form of products, cannot be written with avant-gardist pretensions or with a mindset of leading the way. Such a history must reserve the option to gallop off at a tangent, to be wildly enthusiastic, and, at the same time, to criticize what needs to be criticized. This method describes a pattern of searching, and delights in any gifts of true surprises.

Zielinski’s account of the anarcheological process and the gift of surprise calls to mind improvisation again, while its nod to ‘anarchy’ recalls the punk scene that Patti Smith helped foster in the 1970s. It also fits well with Sandy Pearlman’s description of Smith’s first album:

If poetry like music is born of invention, adventure, of paradoxical limitless individuation, then the first principle of Patti’s excellent adventure [with] Horses was to bet the ranch on a poetic language that directly transforms itself by means of clearly counterintuitive unstaged leaps of word faith, that wind up being perceived at the other end of the combinatorial wormhole as inevitable intuitive logic.

Such ‘leaps of word faith’ are clear throughout Smith’s work, with Banga being no exception. One example would be the inclusion in ‘Constantine’s Dream’ of the ‘coincidence’ of Piero dying in the same year that Columbus reached the New World. A verbal leap at this point allows Smith to indulge her fascination with significant dates while setting up a narrative shift, and 1492 becomes a portal through which musicians and listeners travel to a new stage in the track’s development. This is anarcheology, a willingness to be distracted, to take alternative routes based on emerging possibilities.

In his account of Smith’s work, Tarr frequently uses the term ‘landscape’, which again seems pertinent to archaeological processes because it establishes the notion of a field, something to fill with or empty of objects or people. The canonisation and remembrance of people and the fetishisation of objects have been important factors in Smith’s work. We might conceive of that work and its field as representing an iconscape, a perspective upon the world seen from iconographic reference points, be they religious figures, rock and roll pioneers, or magical relics.

Walter Benjamin also reminds us of ways in which memory can be archaeological when he writes that ‘Language has unmistakably made plain that memory is not an instrument for exploring the past, but rather a medium. It is the medium of that which is experienced, just as the earth is the medium in which ancient cities lie buried.’ The site where we dig for or through memories is important:

Epic and rhapsodic in the strictest sense, genuine memory must therefore yield an image of the person who remembers, in the same way a good archaeological report not only informs us about the strata from which its findings originate, but also gives us an account of the strata which first had to be broken through.

This, again, is a process which takes place in poetic and musical improvisation, the shamanic breaking-through to the other side hymned memorably by Jim Morrison, one of Smith’s influences.

Age, experience and narrative self

Reviews of Banga and the concerts that came in its wake frequently mentioned age, either expressing surprise that Patti Smith was more alive than ever or comparing her, in mostly favourable ways, to contemporaries. Because of Smith’s age and the longevity of her career, the ever-expanding discourse around her allows for a greater intertextuality based on various reference points in that career. Equally, Smith herself promotes connections between age, time and experience with her interests across the arts and her many reference points. As listeners and interpreters of her work, meanwhile, we can make more connections, even if they are not ones the artist intended or would sanction.

For Victor Bockris the ‘late’ Patti Smith went through several personas: in the mid-1990s ‘there were elements of the rebellious punk poet, the grieving widow and sister, caring single mother and committed (a)political activist’, and ‘by 1996 she had metamorphosed from an entertainer into that position Richard Hell had prophesied in his 1974 essay on “celebrity as an art form”. Such a character is a living piece of American history, a walking icon’.

Like most accounts written about what were essentially middle-aged rockers in the 1990s and early 2000s, we have to take all this with a chunk of salt, especially for those musicians who are (thankfully) still with us twenty or thirty years on (I wonder if any age-sensitive archaeologist of 1980s-1990s music journalism has the patience to sift through the many ridiculous claims made about ageing musicians in those years, especially those made about women). But we can take from it the notion that Smith provides an exemplary case of life narrative as adventure and of the self as an open work. She emphasises this with ongoing art projects and by connecting herself to tradition(s). The continued mourning and fascination with memory objects, talismans and magic numbers are all ways of maintaining a chain of experience and affect that stretches from the remembered past through the reflections of the present to the ambitions of the future.

Ageing and the accumulation of experience can be a continuation of the adventure of life, as Smith hints in the subtitle to the 2006 edition of her collected lyrics: ‘Lyrics, Reflections & Notes for the Future’.

Episodes of Smith’s life and the lives of those close to her reverberate through the late chronicles, whether self- or other-authored, and such episodes come to shine like the objects she collects and treasures. A particular story about Smith holding her baby sister Kimberly while witnessing a barn fire features in some of the late chronicles and in a piece from Woolgathering called ‘Nineteen Fifty-Seven’. The poem ‘Kimberly’, which first memorialised this event, also became a song on Horses, thus marking a continuation of certain biographical features over the long range of Smith’s career.

The focus on particular moments and images—a notable feature of Just Kids, The Coral Sea and many of Smith’s poems and songs—calls to mind Roland Barthes’s notion of the ‘biographeme’. In Camera Lucida (a book partly ‘about’ Robert Mapplethorpe in that the latter’s photographs and Barthes’s comments on them appear in it), Barthes notes his fondness for ‘certain biographical features which, in a writer’s life, delight me as much as certain photographs; I have called these features “biographemes”; Photography has the same relation to History that the biographeme has to biography’.

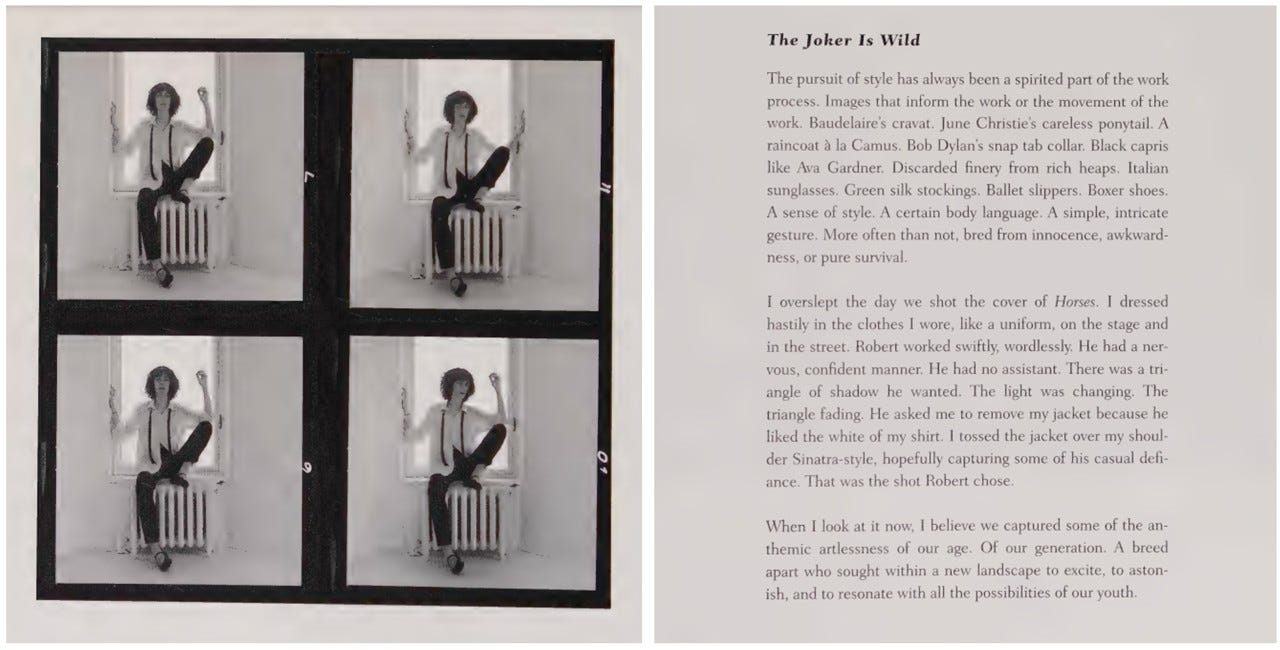

Smith follows a similar line of thinking when refracting such moments through the perspectives of fashion and style:

The pursuit of style has always been a spirited part of the work process. Images that inform the work or the movement of the work. Baudelaire’s cravat. June Christie’s careless ponytail. A raincoat a la Camus. Bob Dylan’s snap tab collar. Black capris like Ava Gardner.

In her writings, Mapplethorpe becomes immortalised, or frozen, as the boy who loved light and placement, while Kimberly remains the babe wrapped in swaddling clothes.

This post has been a bridge between my first run-through of Banga (last week’s post) and my return to it (next week’s), a bridge which I felt had to contend with the weight of Horses. I’ll come back to some of this imagery next week, when I’ll read Banga in connection to Just Kids, Robert Mapplethorpe, and Smith’s ongoing memory work.

I cannot stress enough how much I admire your angle on this essay. You acknowledge the greatness of 'Horses' yet make it clear that Patti's work after that monumental album is often unfairly judged by its standards. Music and art critics are often guilty of this. Thus, an artist tours a specific album and performs it in its entirety. 'Blood on the Tracks' is so often praised, one would think it was Dylan's last great offering. The same is true with Liz Phair's 'Exile in Guyville,' Neil Young's 'Zuma,' and Picasso's 'Guernica.' While these are all superb pieces of art, it is deeply unfair to ignore later works and periods of creation that come after.

Good artists constantly change, challenge themselves, move in different directions, and are inspired by various things. This also changes with time. 'Horses' was recorded at a specific time, and it should be respected as a pivotal piece in her catalogue, but her works that came after should definitely be listened to, appreciated, and critiqued on their own merit rather than judgments based on comparisons to a highly beloved or monumental piece created years before.

I admit I am no expert on her post-'Horses' albums, and I firmly understand this is my own narrow oversight of her catalog, but I would never sit in the pub arguing that Patti's creative peak was 'Horses.' Rather, I would sit back, listen to your take on the post-'Horses' catalog, and then be inspired to explore deeper and with a fresh perspective. Which is precisely what your essay has done (minus the drinks and good craic that meeting up in the pub would include!).

Thank you for this angle and for pointing out the weight that is placed on an artist. In many ways, this is probably why some artists stop challenging themselves and stagnate their sound (Oasis constantly tried to repeat the success of 'Morning Glory' rather than grow). Same with Red Hot Chili Peppers and 'Blood Sugar Sex Magic.' Both bands quickly became boring and put out uninspired music. Meanwhile, a band like Radiohead ignored everything and pushed forward. You never knew what you would get with each new Radiohead album. I suspect Patti's catalog is much the same (deeper explorations and challenging herself as an artist rather than trying to make 'Horses Part II').

Regarding age, this is something that constantly gets mentioned with women artists, actresses, or any high-profile woman. Rarely is age ever mentioned with men. It is sadly a much bigger, societal issue. Especially as most music critics, or those who mention a woman's age, are always men.

I look forward to your third installment in this series, Richard!