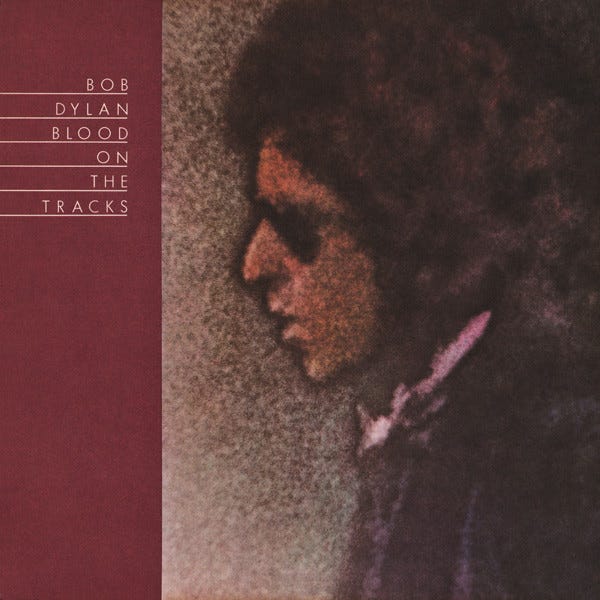

From the Archive: You're Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go

My take on a track from Bob Dylan's 50-year-old Blood on The Tracks.

This is a piece originally published by PopMatters in 2010, as part of a ‘Between the Grooves’ feature on Bob Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks. Given the current interest in Blood’s fiftieth and the Bob biopic, I’m republishing it here as a bonus post for this week. I wrote another piece for the ‘Between the Grooves’ feature, an overview of the album in relation to place and displacement. I republished that yesterday, but didn’t send via email: it’s available here.

‘You're Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go’

It comes on too bright and breezy after the devastation of ‘Idiot Wind’, a bit of light relief, perhaps, to close Side One of Blood on the Tracks. A jaunty harmonica melody, up-tempo guitar strumming, and then that high, pinched Dylan vocal that harks back to the ‘domestic retreat’ albums of a few years before.

Dylan is singing of love coming easy, of it being ‘more correct / Right on target, so direct.’ So direct that the song is treated to one of the neatest, most economical structures to be found on the album. After three verses of domestic bliss, we get a change in scenery. The meter and the music changes and the lyrics move into even softer focus: ‘Flowers on the hillside, bloomin’ crazy / Crickets talkin’ back and forth in rhyme.’ No buzzing flies or raging glory, here; it’s all a bit more Disney than Dylan.

It hasn’t always been slow, lazy rivers and chirping insects, though. Returning to the main verse structure, we hear that the singer’s past relationships have all been bad, ‘like Verlaine’s and Rimbaud[‘s].’ From Bambi to Rimbaud: this is the Dylan we were expecting to hear from, the Dylan who’s recently taken us for a tour through his (or someone’s) tortured psyche. The next time the tune slows, there’s less emphasis on romantic idyll and more recognition that change is coming. The singer’s staying behind and he’s not sure why.

It’s a song about love, then, about the decisions, doubts, and the heartbreak that love brings. It’s an appealing track, not only due to its undoubted hummability, but also to its wise acceptance and modesty. It’s a song that charms.

Paul Williams neatly sums up the appeal: ‘Sure as we’ve all been in love, been loved, we’ve all had the experience of being in someone’s eyes this charming, this much fun.’ Part of the fun is to be found in Dylan’s enjoyment of the words, which, typically for him, are treated in a way that serves song and singer rather than sense. ‘Rimbaud’s’ is actually sung as ‘Rimbaud’, to rhyme with ‘go’, and ‘Honolulu’ becomes ‘Honolula’, to find correspondence with ‘Ashtabula’.

‘There’s no way I can compare / All those scenes to this affair,’ sings Dylan in what might as well be a reference to other songs on the album (‘I know every scene by heart,’ he sings in ‘If You See Her, Say Hello’, while ‘Tangled up in Blue’ is nothing if not a set of scenes). But we, as listeners, can’t help but compare. There are too many ghosts haunting Blood on the Tracks. And even here, that word ‘lonesome’ sticks out from every verse, echoing down through the years and the songs that Dylan has shared with us.

If it wasn’t clear from the refrain, it’s there in the final verse: ‘I’ll look for you in old Honolula / San Francisco, or Ashtabula / You’re gonna have to leave me now, I know.’

Now we know the reason for the nature imagery; it’s a form of mnemonic: ‘I’ll see you in the sky above / In the tall grass, in the ones I love.’ Like the narratives of Townes Van Zandt, a songwriter whose work Dylan has covered, nature is a privileged site for mental impressions that can be stored for future access. ‘Will it be the willow / that hears your lonesome song?’ asks Van Zandt in ‘None but the Rain’.

Others have covered ‘You’re Gonna Make Me Lonesome When You Go’ as primarily a song of departure. Ben Watt of Everything but the Girl provided a reading imbued with mellow regret on his 1982 album North Marine Drive. Over two decades later, Madeleine Peyroux cast the song as a weary late night jazz lament on her album Careless Love (its title taken from the lyrics to Dylan’s song).

Neither artist got it wrong; the song is both weary and mellow, a recognition of inevitable decay postponed rather than dealt with. It’s just that Dylan, recording the original in 1974 amidst the hard memories, accusations and self-recrimination of Blood on the Tracks, found a moment to dwell without regret on the bittersweet nature of passing time.

The end result is a gilded thorn, its barb hidden within that breezy delivery. As it fades out—inviting, in the era of vinyl, a brief reflection before the rigors of Side Two—you could be forgiven for feeling happy about the way things have turned out for this singer.

See also:

From the Archive: The Poetics of Place and Displacement in Blood on the Tracks

This is a piece originally published by PopMatters in 2010, as part of a ‘Between the Grooves’ feature on Bob Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks. Given the current interest in Blood’s fiftieth and the Bob biopic, I’m republishing it here as a bonus post for this week. I wrote another piece for the ‘Between the Grooves’ feature that is just about ‘You’re Gonna …